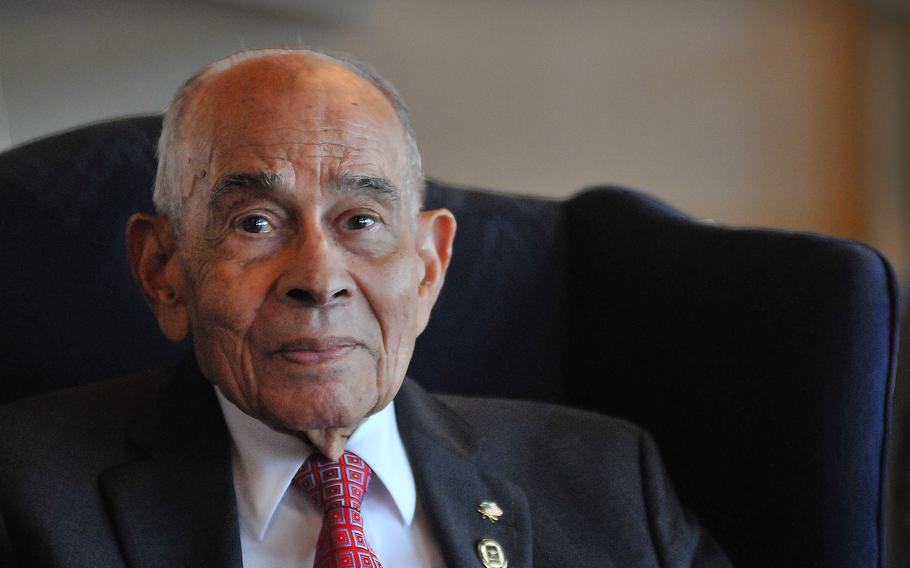

Retired Army Lt. Gen. Arthur J. Gregg poses for photographs at Fort Lee in 2022. The base was renamed Fort Gregg-Adams in 2023 for Gregg and Army Lt. Col. Charity Adams. (T. Anthony Bell)

Retired Lt. Gen. Arthur Gregg, a trailblazing officer who became the Army’s first Black three-star general in 1977 and for whom the former Fort Lee in Virginia was renamed last year, died Thursday, according to the service. He was 96.

Gregg became the first living person in modern American history to have a military installation named for him, when Fort Lee became Fort Gregg-Adams on April 27, 2023, the Army said. The installation, the home of the Army’s logistics training, was renamed for Gregg and another Black officer, Lt. Col. Charity Adams, as part of a Congress-led effort to strip the service of honors for Confederate soldiers, including the post’s former namesake, Gen. Robert E. Lee.

Gregg attended the renaming ceremony last year at the post in Prince George County, Va., and he was known to frequent the installation since the name change, according to the Army news release announcing his death. He was last at Fort Gregg-Adams on July 31 for a change-of-command ceremony.

“The entire Fort Gregg-Adams family is deeply saddened by the loss of a great American and our namesake,” Maj. Gen. Michelle Donahue, the installation’s top commander, said in a statement. “Lt. Gen. Gregg will continue to inspire all who knew him and those who serve at Fort Gregg-Adams now and in the future. His dedication and leadership will never be forgotten. Our deepest condolences to his family and loved ones during this difficult time.”

Gen. Charles Hamilton, commander for the Army Material Command, embraces retired Lt. Gen. Arthur Gregg and Maj. Gen. Mark Simerly, commander for the Combined Arms Support Command, after speaking to the audience at a renaming ceremony for Fort Lee, Va., to Fort Gregg-Adams. (Matthew Adams/Stars and Stripes)

Gregg broke several glass ceilings for Black soldiers. In 1972, he became the service’s first Black brigadier general in its quartermaster corps. Five years later, he became the highest-ranking Black soldier in the Army’s history – at that time – with his promotion to lieutenant general. In 1981, he retired as the Army’s deputy chief of staff for logistics, capping a 35-year career.

Gregg grew up in rural Florence County, S.C., on a 100-acre farm that grew cotton and tobacco, according to an Army profile on his life.

Inspired by the Black soldiers who fought in World War II, Gregg enlisted in the Army in 1946 and was quickly deployed to occupied, post-war Germany to support supply operations, according to this service biography. In 1949, one year after President Harry S. Truman ordered the military desegregated, Gregg entered officer candidate school.

His first assignment as an officer, in 1950, was at Camp Lee, which would become Fort Lee later that year.

His career took him to stops in Japan, several assignments in Germany and jobs at the Pentagon, including as the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s logistics director. In 1966, Gregg commanded the 96th Quartermaster Direct Support Battalion in Vietnam – one of the Army’s largest battalions in the country boasting some 3,600 troops, according to service records.

Gregg said his command experience in Vietnam was “the most significant point” in his storied career.

“It was four-times the normal battalion size, and I’ll tell you, those young people worked their fannies off to build a logistical base and provide logistical support to our forces in Vietnam,” Gregg said in a 2023 Army release. “I was so proud of them.”

Gate sign at Fort Gregg-Adams, Va. Fort Lee was renamed Fort Gregg-Adams on April 27, 2023, in honor of Lt. Gen. Arthur Gregg and Lt. Col. Charity Adams, two Black Army officers who helped pave the way for an integrated military. (Matthew Adams/Stars and Stripes)

Last year, as the Army settled on renaming Fort Lee to Fort Gregg-Adams, Gregg said he was supportive of the effort to strip Fort Lee and eight other southern Army posts of the names of Confederate generals, many of whom were slave owners. However, he said, he was surprised his name would be considered to replace Lee’s.

“I was very honored that they felt I was worthy but, you know, you don’t take it too seriously,” Gregg said at the ceremony to rename the post. “I was aware that there were a number of really outstanding people up for consideration. When the decision was made that the post would be redesignated Gregg-Adams, I was just overwhelmed.”

The so-called Naming Commission, which led efforts to strip honors for former Confederates from the U.S. military, wrote Gregg proved an officer of “great skill, leading by example and embarking on a career of excellence” in announcing its decision to name the base for him and Adams.

“Though Gregg and Adams served on different missions and in different conflicts, consistent themes of leadership, dedication, and problem solving united their service,” the commission wrote in its August 2022 final report to Congress. “Moreover, in overcoming the sustainment obstacles caused by war, they also helped overcome the social obstacles caused by segregation. Their service simultaneously supported mission success and societal progress.”