Romay Johnson Davis served in the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, the only predominantly Black unit of the Women’s Army Corps to serve overseas during World War II. (Women Veterans Historical Project at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro)

Romay Johnson Davis in uniform. (Women Veterans Historical Project at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro)

Romay Johnson Davis, right, with two fellow service members. (Women Veterans Historical Project at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro)

An inspection of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion in Birmingham, England, in 1945. (National Archives)

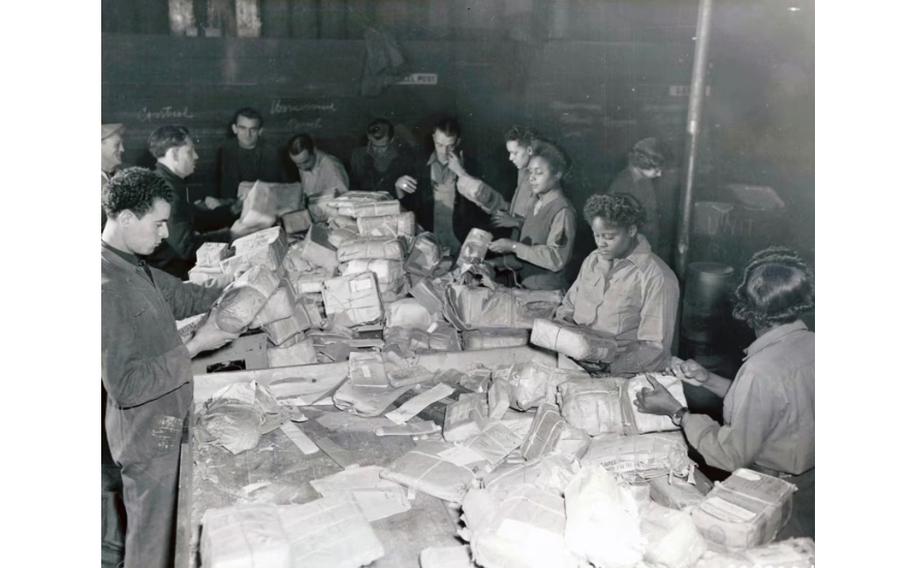

Members of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion sort mail with French civilian employees in Paris in 1945. (National Archives and the National WWII Museum)