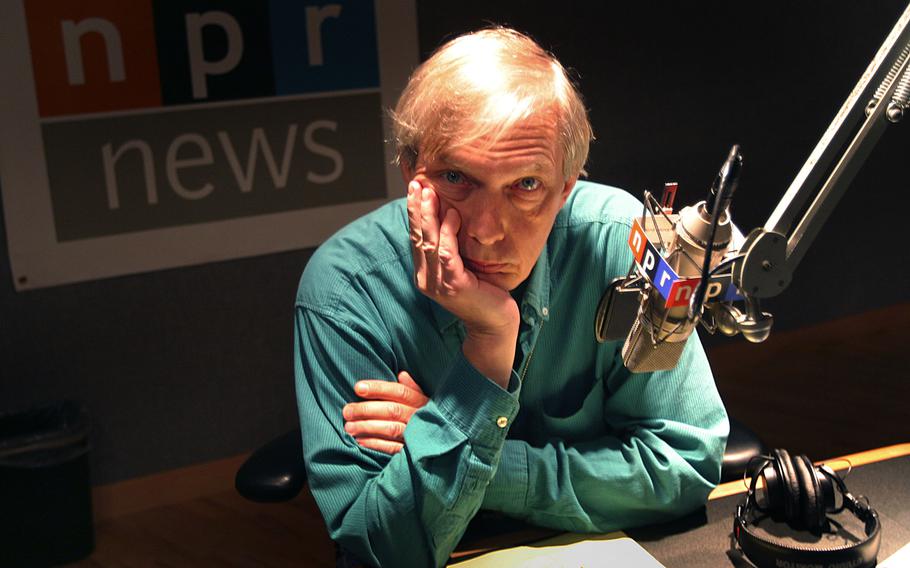

Bob Edwards in the “Morning Edition” studio at NPR in Washington on Feb. 9, 2004. (Lucian Perkins/The Washington Post)

Hours before dawn on Nov. 5, 1979, an NPR team gathered in a studio at the headquarters in Washington. A new show was about to air.

The program already had gone through serious growing pains. Some NPR member stations had complained that earlier test runs had sounded too chatty, too commercial. Emergency overhauls were made, including picking new hosts. One of them was a rising star at NPR with the flagship “All Things Considered” show, who was known for his unflappable demeanor and a basso profundo voice made huskier by a pack-a-day smoking habit.

He had a 30-day trial at the new show. The red “on-air” light blinked on. “Morning Edition” had begun.

“Good morning,” he began. “Today is Guy Fawkes Day. Guy’s plot to blow up Parliament was discovered on this day in 1605. Today is the beginning of National Split Pea Soup Week, and it’s the debut of this program. I’m Bob Edwards.”

Edwards, who died Feb. 10 at 76, stayed at “Morning Edition” for nearly a quarter century and became as much a part of the begin-the-day rhythms for NPR listeners as coffee, commutes and getting the kids off to school. Then in 2004, a decision by NPR to pull Edwards from the show touched off an avalanche of complaints from his fans that even included statements on the Senate floor.

Both his long NPR run and the uproar over his departure reflected Edwards’ deep influence on public radio as it moved from the margins of the national conversation to become a mainstay. His “Morning Edition” interviews — more than 20,000 from 1979 to 2004 — served as an audio scrapbook for a generation and helped establish NPR as a forum for guests to make news or raise their profile.

Edwards interviewed diplomats and autocrats, scientists and artists, the quirky and the powerful. He conducted regular check-ins with personalities such as a former veterinarian turned cowboy poet, Baxter Black, and the wondrously erudite former Major League Baseball announcer Red Barber, who might talk about sports or maybe describe how the lovely dogwoods were blooming outside his home in Tallahassee.

Edwards’ weekly live chats with Barber over nearly a dozen years became a fixture of “Morning Edition.” The freewheeling Barber began calling Edwards “Colonel Bob” after the NPR host was awarded an honorary designation as a Kentucky Colonel.

“Red Barber loosened me up, took me off-script,” Edwards recalled. His book about their collaboration, “Fridays With Red: A Radio Friendship” (1993), was as much about Barber as it was about Edwards’ fascination with radio — which began as a kid in Louisville perched in front of a hulking 1939 Zenith Long Distance Radio in its polished mahogany case.

At “Morning Edition,” he found his place as one of NPR’s most versatile and popular hosts. He pushed his producers to limit interviews with politicians (too predictable, he said) and seek out more artists, activists and lesser-known newsmakers. The goal, he noted, was to find guests who aren’t just spewing rage or talking points.

“This may be a little island of civility and purpose,” he told the Tampa Bay Times in 1999. Once, Julia Child and Paul Prudhomme joined other famed chefs to share Thanksgiving recipes with Edwards. In 1999, Edwards chatted with Baseball Hall of Famer Willie Mays about playing in the fog and swirling winds of San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. (Not so easy, Mays said.)

“He was hugely responsible for shaping NPR’s image, its gravitas, its credibility with his solid, no-nonsense style,” said Michael Harrison, editor and publisher of Talkers, a magazine that covers talk and news radio.

That also may have contributed to his undoing at NPR, Harrison said. By 2004, the pretaped interview format of “Morning Edition” was increasingly regarded as out of sync with demands for more breaking news coverage. This was not Edwards’ forte, said Harrison, and Edwards often seemed uncomfortable when forced into live situations (except for his easy banter with Barber).

NPR said it offered Edwards a new role as a senior correspondent for “Morning Edition” after naming Steve Inskeep and Renée Montagne as the new co-hosts. Edwards opted to leave and soon launched a show on Sirius XM satellite radio.

Bob Edwards with Sen. John W. Warner, R-Va., at the World War II Memorial in Washington in 2004. (Lucian Perkins/The Washington Post)

“This program is the last I shall host,” Edwards told the show’s nearly 13 million listeners just before the final segment of “Morning Edition” on April 30, 2004. “You’re the audience a broadcaster dreams of having.”

For weeks before his final broadcast, the backlash to NPR’s decision boiled over. NPR received tens of thousands of calls and emails protesting the move, some claiming ageism (Edwards was 56) and noting the extra sting that NPR did not let Edwards reach his 25th anniversary on “Morning Edition.” A website gathered signatures with appeals for NPR to change its mind.

NPR ombudsman Jeffrey Dvorkin described the way NPR handled the change as “opaque — perhaps necessarily so.” On Capitol Hill, Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) went on the floor to note the public outcry and applaud Edwards.

How Edwards described his breakup with NPR depended largely on the day he was asked. At times, he spoke of the bitterness about being shown the door when he felt he was still at the top of his craft. Other times, he joked he was grateful because he no longer had a 6 p.m. bedtime.

NPR as an institution, he told an interviewer in 2016, was not to blame.

“With newspapers in decline and commercial broadcasting increasingly shrill, partisan, and often irresponsible, funding for public radio is more important than ever,” he said. “NPR and its member stations are a national treasure.”

Robert Alan Edwards was born in Louisville on May 16, 1947. His father was an accountant and his mother a homemaker. In his 2011 memoir, “A Voice in the Box,” he recounted the Zenith radio from which he could pick up stations as far away as New Orleans.

“Little boys want to be firefighters or athletes or rock stars,” he wrote. “I wanted to be on the radio.”

Edwards graduated from the University of Louisville in 1969 and, as a senior, landed his first radio job across the Ohio River at a station in New Albany, Ind.

He served in the Army during the Vietnam War, producing and anchoring TV and radio news programs for the American Forces Korea Network from Seoul. He found his way to Washington after military service as a news anchor at WTOP while working toward a master’s degree in communications in 1972 from American University. He joined NPR in 1974, four years after its launch.

The run-up to the debut of “Morning Edition” was far from smooth, he recounted. First, the show needed a name; suggestions included “Earth Rise” and “FYI.” The initial concept for the show was spearheaded by two consultant producers hired by NPR from commercial radio. The consultants brought in their hosts: Mary Tillotson, who went on to work for CNN, and Pete Williams, later an NBC News correspondent.

When the pilot shows were piped over to NPR member stations, the responses were harsh. Many thought it was little more than retooled AM news formats. “It was absolutely a disaster. It was very chatty,” Edwards recalled. “It was like bad small-market television.”

The consultants were let go, and NPR tried to remake the show more in its own image, closer to a morning version of “All Things Considered.” Edwards and co-host Barbara Hoctor were given provisional contracts with the show’s future still in question. (Hoctor spent four months on the show, and then Edwards became the lone host.) The first broadcast included an interview with actor Martin Sheen about the film “Apocalypse Now.”

As the show grew a following, producers tried to recruit commentators with distinct regional diversity such as Arkansas novelist Ellen Gilchrist, who mused about writing, and Barber, whom Edwards called “the greatest audience-builder for NPR.”

“You put an Ellen Gilchrist on. You put a Red Barber on,” he said, “and we didn’t sound like this, you know, elite Northeastern U.S., inside-the-Beltway outfit.”

Edwards’ honors include a Peabody Award in 1999 and induction into the Radio Hall of Fame in November 2004. In public events, he poked fun at his hangdog look and retro side-part hairstyle, once saying of his appearance, “There’s a reason we’re in radio.”

During his final months at NPR, Edwards published “Edward R. Murrow and the Birth of Broadcast Journalism” (2004). “The Bob Edwards Show” and a later compilation distributed by Public Radio International, “Bob Edwards Weekend,” ended in 2015. He then hosted a podcast for AARP.

His marriages to Joan Murphy and Sharon Kelly ended in divorce. He married NPR news anchor Windsor Johnston in 2011. In addition to his wife, of the home in Washington, survivors include two daughters from his second marriage, Eleanor Edwards and Susannah Edwards; and a brother. Edwards’ death, at a rehabilitation center in Arlington, Va., of metastatic bladder cancer and a heart ailment, was confirmed by his wife.

Edwards decided to close out his “Morning Edition” tenure the same way it began. His interview subject was CBS News correspondent Charles Osgood, who was also his first one-on-one interview in 1979.

“You’re the alpha and the omega,” Edwards told Osgood.

Edwards in his office at NPR in Washington in February 2004. (Lucian Perkins/The Washington Post)