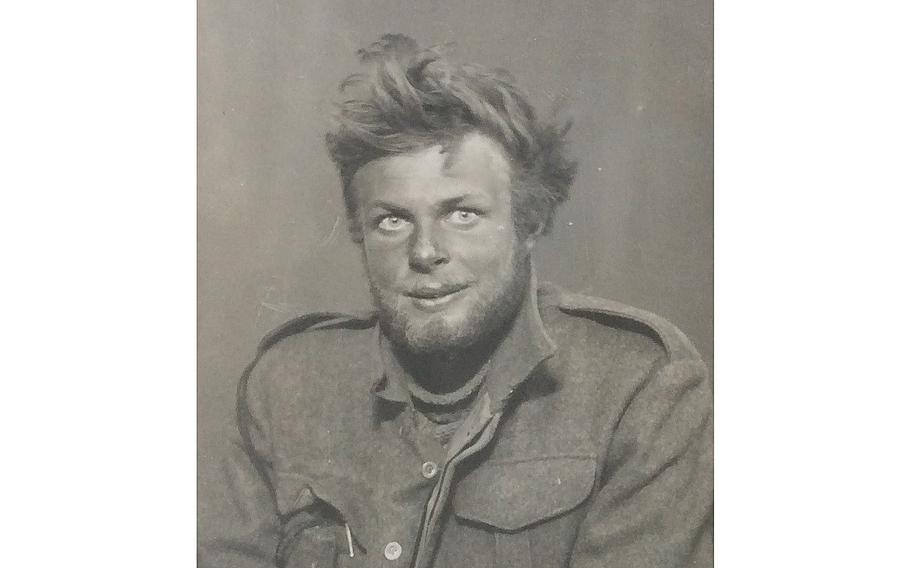

Mike Sadler during World War II. (Family Photo/Courtesy of Blind Veterans UK)

In mid-December 1941, a group of British commandos gathered in the Libyan desert outside an enemy airfield west of Sirte. They had crossed 400 miles during more than two days, driving stripped-down vehicles through wadis and wind-packed sand from an oasis deep in the Sahara.

Their guide, navigator Mike Sadler, was on his first mission, learning to use the sun, stars and surveyor-type instruments to traverse expanses with no roads and few landmarks. “A lot rested on it,” he recalled.

Earlier that year, a British team dropped by parachute suffered heavy casualties against German Gen. Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps. This time, the special forces were attempting a surprise ground attack from the desert.

The British force surged into the Tamet airfield and gunned down German and Italian pilots and crew. At least two dozen planes were destroyed or disabled. A fuel depot was set ablaze. A simultaneous British attack was underway at an air base in Sirte.

Both teams slipped back into the desert night, meeting the navigator at a rendezvous point. The successes set in motion a new guerrilla-style campaign in North Africa by a handpicked group of British munition specialists, gunners, crafty scroungers - and a newly minted navigator who may never have fired a shot.

“Nowadays the SAS has a fearsome reputation,” said Mr. Sadler, who died Jan. 4 at 103, “but I don’t remember ever wanting to kill anybody.”

Mr. Sadler was believed to be the last of the founding members of the SAS, or Special Air Service, the special forces unit of the British army. He also was the only surviving link to the Long Range Desert Group, the roaming expeditionary force that helped the Allies win the battle for North Africa.

Mr. Sadler once even had to use his navigation skills to save his own life. He and two British sergeants escaped after their 15-member unit was captured by a German patrol in January 1943. The trio, with little water, trekked 110 miles in five days to reach a Free French garrison. They were turned over to U.S. forces on suspicion of being German spies.

WWII veteran Mike Sadler in December 2022. (Blind Veterans UK)

“We had long hair and beards and were looking very bedraggled,” Mr. Sadler recalled. “Our feet were in tatters. I don’t think we looked very much like soldiers.”

A group of reporters, including New Yorker correspondent A.J. Liebling, were with the U.S. forces when Mr. Sadler and the two others arrived in camp. “The eyes of this fellow were round and sky blue and his hair and whiskers were very fair,” Liebling described Mr. Sadler in a New Yorker piece. “His beard began well under his chin, giving him the air of an emaciated and slightly dotty Paul Verlaine,” Liebling added, tossing in a reference to the 19th century French poet.

An American intelligence officer, who interrogated Mr. Sadler and the two others, carried a bottle of whiskey. “Which was an excellent idea, because they were pretty well done in by that time,” Liebling wrote. “After half an hour, he climbed out and told us that he thought they were all right.”

Mr. Sadler had arrived in North African as an antitank gunner. At a Cairo bar on leave, he met some of the early recruits to the Long Range Desert Group. He was first considered for the unit because of his weapons experience. On the way to the base, Mr. Sadler became fascinated by celestial navigation. He was offered the role as navigator.

He had just weeks to learn how to use a theodolite, a device used by surveyors, and how to read celestial charts.

“Desert navigation, like its equivalent at sea, is largely a matter of mathematics and observation, but the good navigator also relies on art, hunch and instinct,” author Ben Macintyre wrote in “Rogue Heroes” (2016), a nonfiction account of the SAS operations. “Sadler had uncanny, almost unerring ability to know where he was, where he was going, and when he would get there.”

The desert attack group was dubbed L Detachment - a small ruse to give the impression there were detachments A through K. “I was so tickled,” Mr. Sadler told the BBC History Magazine, “by the idea of being able to find where you were by looking at the stars.”

Mr. Sadler, who was working as a farmhand in British colonial Africa when the war broke out, fit right in with the patchwork of personalities and background on the team - whose exploits have been recounted in books and the current BBC series “Rogue Heroes.” (Mr. Sadler is played by Tom Glynn-Carney.)

Also alongside Mr. Sadler was a war hero from Northern Ireland, Robert Blair “Paddy” Mayne, an expert at hit-and-run strikes who took credit for destroying more than 100 Axis aircraft.

The commandos struck German bases along the Mediterranean coast, taking out more than 325 aircraft, and dozens of key fuel and munition dumps. In one celebrated mission in July 1942, Mr. Sadler led about 100 men in a convoy of 18 Jeeps - each outfitted with Vickers K machine guns - to the Germans’ Sidi Haneish airfield in northwestern Egypt. The site was one of Rommel’s bases for an effort to push deeper into Egypt.

The Jeeps roared onto the airstrip at night and “began to let rip into the parked aircraft,” recalled Mr. Sadler, who was stationed outside the base to help evacuate any possible wounded comrades. At least three dozen aircraft - including Stuka dive bombers, Messerschmitt fighters and Junkers transport planes - were destroyed or badly damaged by machine gun fire.

“Only one of our chaps was hit and killed on the field,” said Mr. Sadler. “Everyone else got away one way or another.”

Mr. Sadler said he tried to never let his gut overrule his observations while navigating.

“You have to be confident because it was awfully easy, especially at night, to start feeling you’re going wrong and you should be further to left or right,” he once told a military historian. “It was rather easy to give way to that feeling if you weren’t confident.”

Fought in Europe

Willis Michael Sadler was born in London on Feb. 22, 1920, and raised in Gloucestershire in western England. His father was a manager of a plastics factory, and his mother tended to their home.

At 17, Mr. Sadler traveled to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) to work on a tobacco farm. When war broke out two years later, he joined the Rhodesian artillery in the British military.

After leaving North Africa, Mr. Sadler was posted to an SAS training center in Scotland and then parachuted into France in 1944 after the D-Day invasion and took part in sabotage operations. He retired as a major.

In the late 1940s, Mr. Sadler and Mayne, his former Detachment L comrade, joined an Antarctic expedition that set up a research base on a glacier (which has since melted) on Stonington Island.

Mr. Sadler later joined the British Foreign Office, working in intelligence during the Cold War. He declined to publicly discuss his duties. Mr. Sadler’s death, in a nursing home in Cambridge, England, was confirmed by a representative of the Special Air Service Regimental Association, a veterans group. No cause was given.

Mr. Sadler’s marriage to Anne Hetherington ended in divorce. In 1958, he married Patricia Benson, who died in 2001. Survivors include a daughter, from his second marriage, Sally Sadler.

Mr. Sadler often said he was well suited for the relative autonomy of the desert missions. Before joining, he objected to a senior officer’s order that soldiers keep their boots on in their sleeping bags. Mr. Sadler voluntarily gave up his sergeant rank rather than apologize.

“I wasn’t at all keen on the extreme aspects of militarism, marching up and down,” he once told a military historian, “although I did my best to be reasonably smart.”