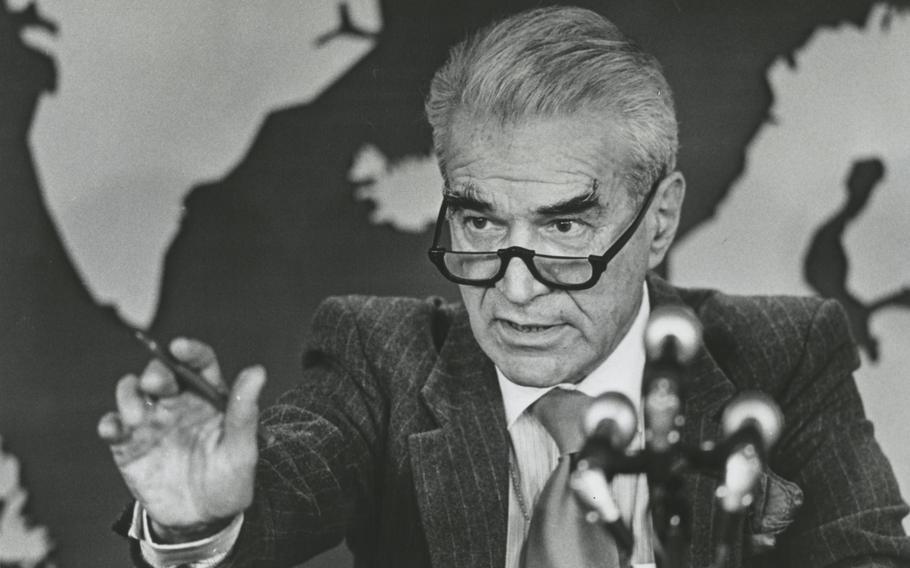

Bernard Kalb, as State Department spokesman, in January 1986. (Joel Richardson/The Washington Post)

Bernard Kalb, a journalist and author who covered global affairs and later cast a critical eye on the media as a commentator for CNN but who may be best remembered for his resignation in 1986 as State Department spokesman to protest a government disinformation campaign, died Jan. 8 at his home in North Bethesda, Md. He was 100.

The cause was complications from a fall, said his younger brother, journalist Marvin Kalb.

In a career spanning six decades, Kalb became a high-profile journalist who crossed paths with some of the most intriguing personalities of his generation. When he was a young Army journalist during World War II, his editor was the detective story master Dashiell Hammett — “a bayonet of a man,” Kalb later recalled, and a “giant of an author who took a bunch of semiliterate kids and turned them into amateur newsmen.”

At the New York Times after the war, Kalb worked his way from the radio desk to overseas assignments. He accompanied arctic explorer Adm. Richard E. Byrd to the South Pole in the winter of 1955-1956. During the four-month expedition, Kalb later quipped, his hardest feat was finding synonyms for the word “ice” and avoiding the cliche “bottom of the world.”

He covered the United Nations and the crisis-laden rule of Indonesia’s President Sukarno before switching to TV journalism in 1962 and opening the CBS News bureau in Hong Kong. He won an Overseas Press Club Award for a 1968 documentary on the Viet Cong and accompanied President Richard Nixon on his historic trip to China in 1972.

Kalb also was a Washington anchorman of the “CBS Morning News,” among other assignments, but distinguished himself most on the State Department beat, covering five secretaries of state from Henry Kissinger to George Shultz. With his younger brother, Marvin, also a broadcast journalist, Kalb wrote an early biography of Kissinger.

The Kalb brothers both made the leap from CBS to NBC in 1980. Bernard Kalb then joined the Reagan administration in January 1985 as assistant secretary of state for public affairs. “This was nothing I sought to create or devise,” he told The Washington Post at the time, describing the offer as “an opportunity that came out of some marvelous blue.”

Lanky, darkly handsome, bombastic, jocular, cigar-wielding and given to what The Washington Post called “garish shirt-and-tie combinations” heavy on stripes and burnt-orange, he was an unlikely public face of the reserved and comparatively colorless Shultz.

As spokesman, Kalb was less than forthcoming with information (“I can’t be drawn into discussions on confidential exchanges,” he said in response to one query) and began to develop a reputation among journalists for being deliberately unhelpful or else utterly out of the loop.

“I had high visibility, easy access — and silence,” he once told The Post. “I discovered that the job of spokesman is regarded as the world’s seventh-oldest profession. The other six obviously are classified.”

Henry and Nancy Kissinger, left, joke with Bernard Kalb, right, Marvin Kalb, second from right, and Arthur Thornhill Jr., president of Little, Brown and Company, in 1974. (Bob Burchette/The Washington Post)

United Press International reported that he had “set a new record for State Department non-responsiveness” in August 1986 by saying, in effect, “I can’t give you anything on that” to 30 questions in one 24-minute briefing.

That October, Kalb said he was caught by surprise when Post journalist Bob Woodward revealed a secret White House plan that called for the deliberate planting of false information in the U.S. media to weaken Libyan leader Moammar Gaddafi.

Quoting from a memorandum sent to Reagan by national security adviser John M. Poindexter, Woodward wrote that a key element of the plan was to combine real and illusory events to make Gaddafi think “that there is a high degree of internal opposition to him within Libya, that his key trusted aides are disloyal, that the U.S. is about to move against him militarily.”

The information was planted first in the Wall Street Journal, where White House spokesman Larry Speakes confirmed that it was authoritative, and then picked up by other news organizations.

Kalb, who said he had known nothing of the plan, quit. His departure caused an avalanche of headlines and set off a public examination of media-government relations.

“You face a choice — as an American, as a spokesman, as a journalist — whether to allow oneself to be absorbed in the ranks of silence, whether to vanish into unopposed acquiescence or to enter a modest dissent,” Kalb said at a news conference at the State Department. He avoided criticizing Shultz, whom he called “a man of integrity.”

Shultz, while admitting to no specific disinformation scheme, appeared to defend the disinformation policy in principle, quoting Britain’s World War II prime minister, Winston Churchill, as having said, “In time of war, the truth is so precious, it must be attended by a bodyguard of lies.”

It was a rare act for a press secretary to so publicly quit and cite ethical qualms. White House spokesman Jerald terHorst resigned in 1974 after President Gerald Ford pardoned Nixon for Watergate-related crimes. Reagan deputy White House press secretary Les Janka stepped down in 1983 to protest what he claimed was an effort to mislead reporters about the Grenada invasion.

Regarding Kalb, Hodding Carter III, who served as State Department spokesman in the Jimmy Carter administration, told the Los Angeles Times that he found it “refreshing that in a town full of careerists, someone decided that what brought him into government was what took him out — integrity.”

Kalb went on to host CNN’s media-critique show “Reliable Sources” for much of the 1990s, until he was succeeded by then-Post media writer Howard Kurtz.

Bernard Kalb was born in Manhattan on Feb. 4, 1922, to Jewish immigrants from czarist Russia. His father became a tailor, and his mother was mostly a homemaker.

After graduating in 1942 from City College of New York, Kalb joined the Army and was sent to Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, where he worked on a newspaper under Hammett.

Kalb joined the Times in 1946 and languished for nearly a decade as a writer for the newspaper’s radio station, WQXR, despite what peers such as Arthur Gelb — later a top editor — recognized as his “flair” and a burning ambition to become a foreign correspondent. Finally, in 1955, he was assigned to chronicle Operation Deep Freeze, Byrd’s final expedition to Antarctica — Kalb’s big break in journalism.

In 1958, he married Phyllis Bernstein. In addition to his brother, of Chevy Chase, Md., and his wife, of North Bethesda, survivors include four daughters, Tanah Kalb of Westport, Conn., Marina Kalb of Brookline, Mass., Claudia Kalb of Alexandria, Va., and Sarinah Kalb of Israel; and nine grandchildren.

After “Kissinger” (1974), Kalb and his brother wrote a novel, “The Last Ambassador” (1981), about the fall of Saigon.

The Kalb brothers were fond of self-deprecating remarks about sibling rivalry, exacerbated by a shared profession. Both liked to tell the story of their mother phoning CBS, where they worked at the time, and asking the person who answered, “This is Marvin Kalb’s mother. Is Bernie around?”

In a note in their Kissinger biography, Bernard and Marvin signed a statement attesting that “my brother” was responsible for any errors.