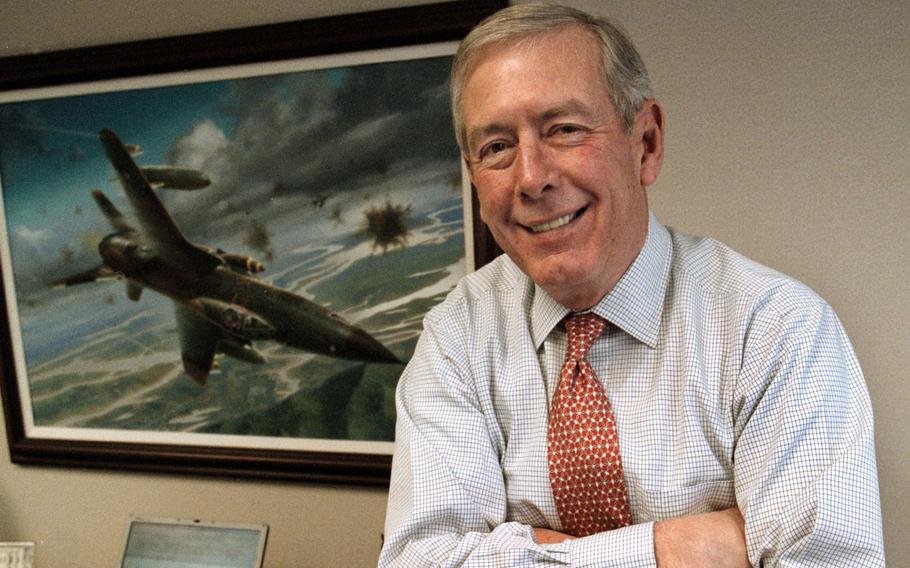

Charles G. Boyd, a retired Air Force general and Vietnam POW, led the Washington-based group Business Executives for National Security. (Frank Johnston/The Washington Post)

Charles G. Boyd, a highly decorated Air Force general who was shot down as a fighter pilot during the Vietnam War, endured nearly seven years of captivity and rose to become the only former POW from that conflict promoted to a four-star rank, died March 23 at a hospital in Haymarket, Va. He was 83.

The cause was complications from lung cancer, said his son, Dallas Boyd.

A 36-year veteran who held posts in Europe, Southeast Asia and the Pentagon, Gen. Boyd retired from the Air Force in 1995 after serving as deputy commander of the U.S. European Command in Stuttgart, Germany, with an area of responsibility spanning 82 countries. He later served as executive director of the Hart-Rudman Commission, a congressionally chartered panel that reviewed the state of national security and - seven months before the 9/11 terrorist attacks - called for the creation of a new agency similar to what became the Department of Homeland Security.

Active in the realm of foreign affairs long after his retirement from the military, Gen. Boyd went on to warn against a unilateral U.S. invasion of Iraq, declaring that the “cakewalk” that some observers anticipated for American forces trying to replace Saddam Hussein would “never happen.” He was also a senior vice president of the Council on Foreign Relations, president and chief executive of Business Executives for National Security and chairman of the Center for the National Interest, a Washington think tank.

But as he saw it, “the defining experience” of his life was the 2,488 days he spent in confinement in North Vietnam, where he was tortured and beaten at prisons including Hoa Lo, a notorious detention center that American POWs nicknamed the Hanoi Hilton. For about 18 months, he occupied a cell next to a young naval officer, John S. McCain, and got to know the future U.S. senator and Republican presidential candidate by communicating through a series of coded taps on the wall, which POWs used to share stories and information.

The prolonged malnutrition he suffered in captivity led to vision problems that ended his career as a military aviator. Long after he was released in 1973, he returned to Southeast Asia to retrace his wartime steps and found himself overwhelmed by memories. For years, he rarely spoke about his experience as a prisoner, saying he wanted to look forward, not back.

“I made a significant effort in my life, and I think fairly successfully, to put that all behind me,” he told Airman Magazine, an Air Force publication, in 2016. “I’d lost about a fifth of my life at that point,” he added, “and I didn’t want to waste any more feeling sorry for myself or fussing over what otherwise might have been.”

Charles Graham Boyd was born in Rockwell City, Iowa, on April 15, 1938, and grew up working on his family’s farm. At age 7, his father paid for him to take a 15-minute flight on a crop duster. It was his first plane ride, and transformed an interest into an obsession.

“For a preteen farm boy from Iowa in bib overalls, in a family of very modest means, that was a really big dream - rather like, say, going to the moon,” he recalled in a 2019 oral history interview with the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training.

Gen. Boyd studied for two years at Baylor University in Waco, Tex., before learning about the Air Force’s aviation cadet program, which offered him a chance to become an officer and a pilot without receiving a degree. He signed up in 1959 and was deployed in 1965 to Thailand, where he went on bombing missions to North Vietnam and Laos, flying a supersonic F-105 Thunderchief fighter-bomber.

On April 22, 1966, during his 88th mission over North Vietnam, he volunteered to participate in an operation to destroy surface-to-air missile sites on the outskirts of Hanoi. He evaded a pair of missiles and continued his attack before being hit by antiaircraft fire, according to his citation for the Air Force Cross, the service branch’s highest decoration after the Medal of Honor.

“The selfless act of making repeated attacks through intense ground fire after barely avoiding two missiles was far beyond the normal call of duty,” the citation said.

Gen. Boyd recalled that his plane was damaged so severely he was forced to bail out at a dangerously high speed; his helmet was ripped off his head as he exited the aircraft. Parachuting into a rice paddy, he landed with scraped cheeks but no broken bones and was immediately captured by North Vietnamese wielding AK-47s.

Much of his captivity was spent in isolation, either in solitary confinement or with a fellow POW or two in his cell, although a few months after his capture he and some 50 other prisoners were forced to participate in a propaganda demonstration known as the Hanoi March. Paraded through the North Vietnamese capital, they were beaten and attacked by civilians along the way.

Gen. Boyd was released in February 1973, days after the Paris Peace Accords ended U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. By then he had vowed to return home “a different and better man,” including a better husband. His marriage to Millicent Sample, a schoolteacher, had been strained, he said, but they renewed their vows at a hospital chapel shortly after he returned, and remained together until her death in 1994.

Readjusting to life outside of captivity, he enrolled at the University of Kansas to pursue Latin American studies, an interest he had developed while in Vietnam, where a fellow POW used the “tap code” to teach him basic Spanish. “The big calluses on my knuckles from tapping so much lasted close to 10 years after I came home,” he told a University of Kansas interviewer.

He received a bachelor’s degree in 1975 and a master’s in 1976, and continued his military education at the Air War College at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama.

Gen. Boyd later served as vice commander of Strategic Air Command’s 8th Air Force in Louisiana, director of plans at Air Force headquarters and commander of Air University in Alabama before being appointed to U.S. European Command in 1992. His military decorations included the Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star, Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star Medal and Purple Heart.

In 2005, Gen. Boyd married Jessica Tuchman Mathews, a former member of The Washington Post editorial board and president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, retiring with her to a farm outside Marshall, Va. In addition to his wife and son, of Falls Church, Va., survivors include a daughter, Jessica of Corona, Calif.; a sister; and four grandchildren.

Although vision problems stymied his career as a fighter pilot, Gen. Boyd rode a BMW motorcycle into his late 70s and continued to fly until last fall, including on a T-34 Mentor, the same single-engine aircraft he had trained on. Some of his other habits started to change, however. He noted that he had been “a Republican, but quietly” since his return from Vietnam, and served as a military adviser to Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) in the 1990s. Yet he largely stayed out of national politics until 2020, when he joined nearly 500 former senior military and civilian leaders in signing an open letter in support of Joe Biden’s presidential campaign.

“I fervently believe that military officers should not get involved in presidential politics, even when retired,” he said in a video he recorded for the group’s Twitter account. “But this year is different. Donald Trump’s assault on the rule of law that makes a democracy possible has been so egregious I’ve decided to speak out.”

He was voting for Biden, he added, and hoped others would do the same.