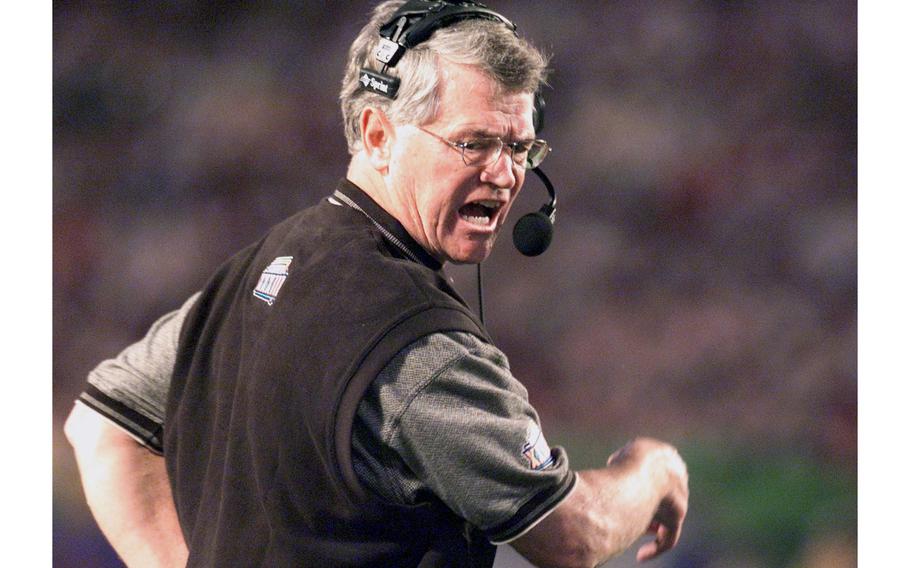

Atlanta head coach Dan Reeves, formerly the head coach of the Denver Broncos, reacts to a call by the referees in the first half of Super Bowl XXXIII, at Pro Player stadium in Miami, Fla., on Jan. 31, 1999. Atlanta lost to Denver 34-19. According to reports on Saturday, Jan. 1, 2022, Reeves has died. He was 77. (ROBERT SEAY/MACON TELEGRAPH /TNS)

ATLANTA (Tribune News Service) — Dan Reeves’ career once was described as a thread that runs through football for 35 years.

From Rome, Ga., to Columbia, S.C., to Dallas, Denver, New York and finally Atlanta, Reeves played or coached with integrity and, typically, positive results.

Reeves, who coached the Falcons from 1997-2003 and led the team to its first appearance in the Super Bowl, died early Saturday at the age of 77 because of complications from a long illness, according to his family.

The Reeves family issued a statement: “Legendary NFL player and coach Dan Reeves passed away early this morning, peacefully and surrounded by his loving family at his home in Atlanta, GA. He passed away at age 77 due to complications from a long illness. His legacy will continue through his many friends, players and fans as well as the rest of the NFL community. Arrangements are still to be determined.”

It was a career of milestones: More than 200 wins, 50 playoff appearances, two Super Bowl wins, a touchdown pass thrown in the Ice Bowl.

And of character.

“He’s a guy in a highly competitive game who remained likable,” former Buffalo coach Marv Levy told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2003. “That’s a pretty fair balance.”

Reeves coached the Falcons from 1997-2003.

“Dan Reeves leaves a lasting legacy in our game as a player and coach. His track record of success in Dallas, Denver, New York and Atlanta over several decades speaks for itself, marking a long and successful life and career in football,” Falcons owner Arthur Blank said in a statement. “On behalf of the Atlanta Falcons I extend our condolences to Dan’s family and friends as they mourn his passing.”

Super Bowl XXXIII, which ended with a 34-19 Dallas Cowboys defeat of the Denver Broncos, was one of nine he appeared in as a player (Cowboys), assistant coach (Cowboys), or head coach (Broncos, Falcons). He won two of them: Super Bowl VI as a player and XII as an assistant coach, both with the Cowboys.

Reeves led the Falcons to success at a level the club had seldom experienced. After a rough first season in 1997, which is typical for new coaches taking over poor franchises, the team began to coalesce behind quarterback Chris Chandler, running back Jamal Anderson, defensive end Chuck Smith, linebacker Jessie Tuggle and the rest of the “Dirty Birds.” The following season, in 1998, the Falcons were on their way to the Super Bowl.

While defeating the Saints, 27-17, in New Orleans late that season, Reeves experienced a burning sensation in his throat. He was examined, and the diagnosis Dec. 13 was that he needed quadruple bypass surgery. The operation was performed the next day. Reeves was 54 years old.

“I was very lucky,” Reeves said in 2011. “It was almost a miracle. If I hadn’t said something about the symptoms ...”

There were three games remaining in the season and the team was trying to hold off San Francisco to win the NFC West division.

Rich Brooks took over as interim. The team kept rolling. They won the division with a 14-2 record.

Reeves stunned everyone by returning less than four weeks later.

The Falcons defeated San Francisco in the first round of the NFC playoffs and then knocked off juggernaut Minnesota, which was 15-1, in the NFC Championship game, 30-27, on a 38-yard field goal by Morten Andersen in overtime. It was the team’s first appearance in the championship game.

“It was just a great year,” Reeves told the AJC in 2019. “We had a lot of things that happened with the team coming together and playing as well as it did. It started the year before with a good run.”

On Jan. 31, 1999, the Falcons met the Broncos, Reeves’ former team, in the Super Bowl in Miami. That appearance was supposed to be the highlight of a successful season. Instead, safety Eugene Robinson was arrested the night before the game. Then in the game, Denver, led by John Elway, jumped to a 17-6 lead.

That proved more than enough in a 34-19 Broncos victory.

“It was a great team effort,” Reeves said in 2019. “The whole season was just a special year. It certainly ended up on a high note. Unfortunately, we didn’t play as well as you have to play. When you get to the Super Bowl, you have to play your very best. We had some distractions and didn’t play as well as we could play and got beat.”

Reeves even joined in with his team to celebrate victories with a dance, known as the Dirty Bird, complete with flapping arms.

Reeves wasn’t able to get the Falcons back to that big stage. They finished 5-11 in 1999, 4-12 in 2000, 7-9 in 2001, 9-6-1 in 2002 and then 3-10 in 2003. In 2003, Reeves was told by second-year owner Blank that he would not be back the following season. Reeves chose to leave immediately.

When he was fired by the Falcons, Reeves asked to be released from his contract so that he could pursue other opportunities. Blank agreed but paid him for the remainder of the contract anyway.

“If the decision had already been made to release me, my feelings were that I would like it to be effective immediately,” Reeves said in the hours after he was let go. “It’s like me calling in a player and saying, ‘I’m going to release you, but I want you to play three more games until I find somebody to replace you.’ “

Though he interviewed at a few places, Reeves never worked for another team in the NFL. He finished with a record 201-174-2 as a coach, including 49-59-1 with the Falcons. He also was a head coach for the New York Giants.

Reeves did some work in television and also served as a consultant for Georgia State when it was researching whether to start a football program. He also did some work for a local radio station in Atlanta.

Reeves was born in Rome on Jan. 19, 1944.

He became a multi-sport standout at Americus High School and earned a scholarship to play football at South Carolina.

Reeves became a three-year starter at quarterback for the Gamecocks, setting numerous school records. Though more of a running quarterback, he passed for 2,561 yards and 16 touchdowns. He also played right field for the baseball team. He was inducted into the state of South Carolina’s Athletic Hall of Fame in 2006.

After his eligibility ended at South Carolina, Reeves wasn’t drafted, but he signed as a free agent with the Cowboys in 1965.

He once told a story about flying to training camp with two other notable rookies: Bob Hayes, the gold medal-winning Olympic sprinter from 1964, and Jethro Pugh, who at 6-foot-6, 250 pounds was considered huge then.

“I’m going, Holy mackerel, the world’s fastest human and the biggest man I’ve ever seen, and I’m going to training camp to fight for a position with these guys,” Reeves said in 2009.

Reeves not only competed, but he thrived.

Though he signed with the Cowboys as a safety, Reeves was moved to running back by legendary coach Tom Landry in 1966 and led the team in rushing and was second in receiving. He set a then-franchise record with 16 touchdowns.

After sustaining a knee injury that limited his ability, Reeves became a player-coach for Landry. Reeves retired as a player after the 1971 season, finishing with 1,900 rushing yards, 1,693 receiving yards and 42 touchdowns. The highlight was defeating the Dolphins, 24-3, to win the Super Bowl VI in 1972.

Reeves served as an assistant coach with the Cowboys until he was named the Broncos coach in 1981. He led the Broncos to three Super Bowls, losing to the New York Giants in 1986, Washington in 1987 and San Francisco in 1989.

Reeves coached the Giants from 1993-96. He led the Giants as far as the NFC divisional playoffs in 1993, for which he was named the NFL Coach of the Year.

Throughout, Reeves was known as a man of integrity and great character.

If he wanted, he could have become Georgia State’s first football coach, but he wouldn’t pursue the job and modest salary because he said he wanted to get back into the NFL.

He turned down a job as San Francisco’s offensive coordinator to pursue an opportunity with the Cowboys in 2009. His daughters lived there. It was better for his family. But it didn’t work out with Dallas because the language in the contract wasn’t quite right, and it was important to him that it be accurate.

Reeves was tough, but fair.

“He held coaches accountable, and he would get on them hard, but he would relax sometimes,” Emmitt Thomas said of Reeves in 2008.

Though he once compared coaching in the NFL with something one never gets over, he wasn’t consumed by his responsibilities.

In 2003, his last with the Falcons in a year partially undone by Michael Vick’s injury, Reeves still took time to try to lift the spirits of a young man dying of leukemia. It wasn’t a one-off. Reeves would check on the young man. He shared the cell phone number for the child’s father with other Falcons such as Vick, Warrick Dunn and Keith Brooking. They also began calling to try to help the young man.

“Wins and losses on a football field are but a fleeting memory. The strength of character is the true sign of success,” the child’s father, Clay Owen, wrote about Reeves in 2003.

___

©2022 The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Visit at ajc.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.