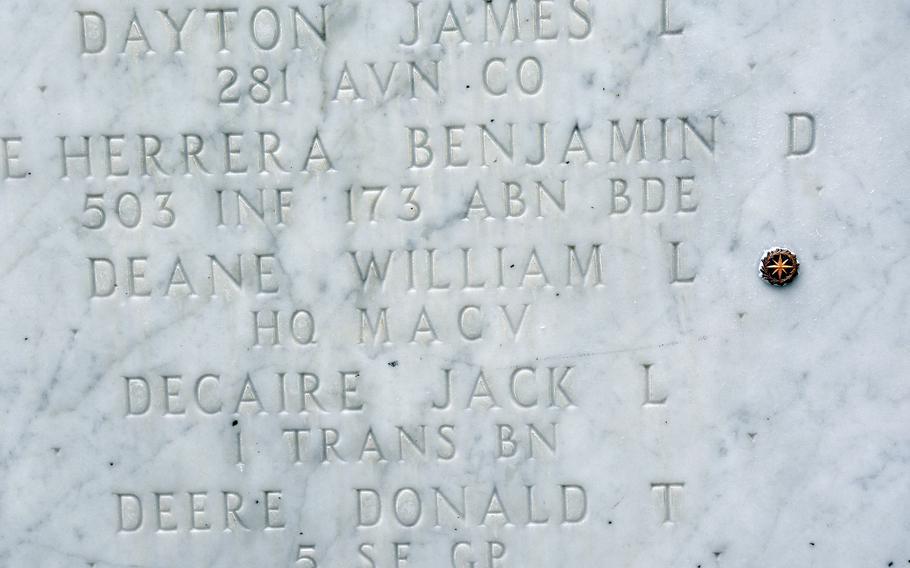

Sharon Deane places a bronze rosette beside the name of her father, Army Lt. Col. William Deane, at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu on Sept. 20, 2024. His missing remains from the Vietnam War were identified in 1999. (Wyatt Olson/Stars and Stripes)

NATIONAL MEMORIAL CEMETERY OF THE PACIFIC, Hawaii — Sharon Deane crouched in front of the Courts of the Missing monument in Honolulu on Friday morning and completed a long-overdue honor for her late father.

She placed a small bronze rosette beside the name of Army Lt. Col. William Deane, who went missing in action in Vietnam in 1973 after being shot down over Quang Tri Province.

His name, along with 2,503 other service members whose remains could not be found at war’s end, are etched in marble on two walls of the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. Similar walls list the missing from World War II and the Korean War.

Deane’s remains were recovered and identified in 1999, and that change of status to “accounted-for” should have been reflected by the inclusion of a rosette.

But Deane and just over 950 formerly unaccounted for troops from the Vietnam War had never received their rosettes.

The first of them got their due Friday during the annual National POW/MIA Recognition Day at the cemetery.

A Gold Star family member from each of the five service branches placed rosettes into predrilled holes next to the names of their loved ones.

Drilling has been completed beside the 900-plus other names, and rosettes will be pressed into them in the coming days.

The American Battle Monuments Commission oversees the Courts of the Missing and is in charge of placing the rosettes.

The name of Army Lt. Col. William Deane, who went missing during the Vietnam War, received a bronze rosette during a ceremony at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu on Sept. 20, 2024. The rosette indicates his remains have been accounted for. (Wyatt Olson/Stars and Stripes)

It remains unclear why the commission fell decades behind in attaching rosettes on the Vietnam walls, but last year two daughters of Vietnam War pilots killed in action set out to rectify the lapse.

Natalie Rauch, a longtime Hawaii resident, was 8 years old in 1966 when her father, Air Force Col. Warren Anderson, disappeared in the reconnaissance jet he was piloting over North Vietnam. His remains have not been found.

Colleen Shine, of Arlington, Va., was also just 8 when her father, Air Force Lt. Col. Anthony Shine, went missing in 1972 while flying a reconnaissance jet over the Laos border. His remains were identified in 1996.

“This is an unprecedented and inspiring coming together of mission and creed, of government agencies, MIA and Gold Star families, veterans and community,” Shine told the audience during the ceremony.

“To the 1,574 brave families who still actively seek answers to the fate of your missing loved ones, we are with you,” Shine said, referring to the number of service members still unaccounted for from the Vietnam War.

Sandra Sylvester, who attended the ceremony with her daughter Suzanne Sylvester, lost her husband, Air Force Capt. Raymond Salzarulo Jr., in 1966 when he was shot down in Vietnam. He was accounted for in 1991.

The elder Sylvester said attending the ceremony was to benefit her daughter more than herself.

“There’s a time frame for the normal things that you do when somebody has died, a grief process, which Suzanne never knew,” she said of her 58-year-old daughter who was an infant when her father was shot down.

“She only knew she didn’t have her father, so it’s just important to me to kind of find closure,” she said. “It was something we could do together. And it was time. It was time.”

The name of Suzanne’s grandfather, Raymond Salzarulo Sr., who went missing during World War II, appears elsewhere in the Courts of the Missing. He remains missing.

It is a family legacy that the younger Sylvester cannot fully comprehend.

“My understanding is my dad kind of went off to finish what his dad had started, or continue it, or however you want to word it,” she said.

Active and retired service members lay wreaths in honor of the missing during the National POW/MIA Recognition Day ceremony at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu on Sept. 20, 2024. (Keion Jackson/U.S. Army)

A missing family member is a profound trauma to those who wait, Sharon Bannister, a retired Air Force major general, said during the ceremony’s keynote address.

Her father was shot down over Laos on March 7, 1972, just days before her 6th birthday.

“Words really don’t describe the years to follow,” she said.

“There’s just so many unknown answers to questions,” she said, pausing at times to compose herself.

“There’s an aching heart that never heals. It’s a feeling that’s really hard to explain. When you’re left to come up with your own story, you make it up. You make up the story.”

In 2007, Bannister got the answers to some of her questions when the forensic lab in Hawaii identified her father from two teeth recovered from a crash site.

“They placed two teeth in my hand,” she said of her visit to the lab to collect the remains.

“I was finally able to close my palm, and I felt like I was hugging my dad. I knew he was home.”