Jose Marquez stands outside of his building, after his return to the United States. (Natalie Keyssar for The Washington Post)

NEW YORK - Jose Marquez served three years in the U.S. Army and five years in the reserves, but because of convictions for drug crimes, federal judges ordered him deported to the Dominican Republic, the country he left as a child.

His lawyer, voice cracking, told Marquez in a New York detention center that he would be barred from the United States forever. Marquez refused to accept that he would never return, even as immigration officers escorted him onto the airplane.

He kept thinking about the mantras he learned in the military.

“It’s not over,” he said then, nearly 20 years ago.

In 2005, Marquez became one of the estimated hundreds of veterans deported from the United States over the past few decades, though U.S. officials have acknowledged that they have never counted them all. Many were deported because they were arrested for crimes involving drug abuse, which veterans advocates say often stems from service-related injuries, trauma and stress.

President Biden, during his campaign ahead of the 2020 election, promised to bring back deported service members, saying he understood their plight because his late son, Beau, had served in Iraq with the Delaware Army National Guard.

“Anybody who’s fought for the United States of America should not be in a position to be deported,” Biden said during a 2019 campaign stop in Nevada.

After Biden took office, his administration created a program that allows deported veterans to apply to return to the United States for humanitarian reasons. Advocates say U.S. veterans often face danger in other countries, such as inadequate medical care or threats from cartels for their loyalty to U.S. forces.

Since the program began, 120 deported veterans have returned to the United States, according to the Department of Homeland Security. Most are on a temporary status for humanitarian reasons, giving them access to U.S. health care and a chance to find a way to stay permanently.

Veterans advocates have been urging Congress to create a path to citizenship to prevent such service members from facing deportation again.

An old friend runs into Jose Marquez for the first time since Marquez returned to the United States, outside a bodega near his home in New York. (Natalie Keyssar for The Washington Post)

“They sacrificed for this country and suffered the consequences,” said Jennie Pasquarella, a lawyer with the Seattle Clemency Project and longtime veterans advocate who said the number of returned veterans has increased substantially. “It’s incumbent upon us as a society to take care of them.”

Marquez’s parents came to the United States from the Dominican Republic in the 1960s and then sent for their children in 1976, when he was 12. His mother, Maria, stitched medical scrubs at a factory in New York City’s Washington Heights neighborhood, and his father, Jose, cooked steaks at a grill. Marquez joined the swim team at George Washington High School, sold shoes at Thom McAn and studied at Brooklyn Technical College.

After the 1983 attack on a Marine Corps barracks in Beirut, which killed 241 service members, he and a handful of friends enlisted in the military.

He served mainly at Fort Hood in Texas, training as a mechanic and marksman.

One day, he said, a supervisor told him to apply for U.S. citizenship so he could qualify to be an officer, though he never made it that far, court records show. Marquez said he turned in the paperwork and believed that made him a citizen.

Marquez was honorably discharged in 1993. In New York, he found work as a lifeguard and then became a maintenance manager for a fitness club chain.

Then, he said, “my ma got sick.”

After his mother was diagnosed with cancer in 1995, Marquez said, he spiraled into depression, alcohol and drugs. From 1996 to 1998, he was arrested and convicted on three counts of buying or selling cocaine and sentenced to seven years to life in prison, court records show.

Many veterans struggle after their service, and a recent Council on Criminal Justice report showed that as many as 1 in 3 say they have been arrested at least once, compared with fewer than 1 in 5 nonveterans. Only noncitizens face deportation, and jails are one of the main ways that immigration agents find potential detainees.

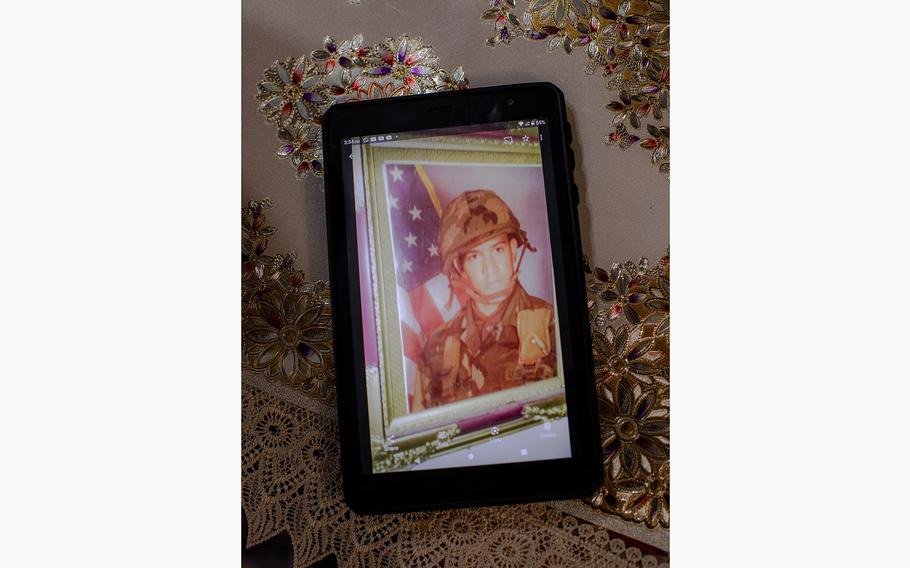

A photo of Jose Marquez in uniform from when he was in the U.S. Army. (Natalie Keyssar for The Washington Post)

Marquez said an immigration agent approached him during a stint on Rikers Island, a city prison complex that at the time allowed federal immigration agents to scour the inmate roster for noncitizens to deport.

“I’m a United States citizen,” he recalled telling the immigration agent at the time, believing it was true.

The Army had taken care of it, he said then.

The Army had not.

Marquez did not have a lawyer when a judge ordered him deported.

Attorney Peter Markowitz, who had graduated from New York University School of Law, agreed to take on his case for free. Markowitz had also grown up in Washington Heights, a few blocks from the Marquez family.

Markowitz argued that deporting veterans was “an insult” to all those who served, according to federal court records. Marquez had taken an oath of allegiance to the Army, he argued, and that meant he belonged in the United States.

The appeals court disagreed, saying he was a foreigner who could be deported.

“I felt like I was betrayed,” Marquez said.

Over the next two decades, Marquez and Markowitz fell out of touch. Markowitz felt he had failed one of his own neighbors in his first case. He devoted much of his life to preventing it from happening again.

Markowitz, among other accomplishments, led the creation of a public-defender program for detained immigrants facing deportation, which has since been expanded statewide.

A wall of family portraits in the living room of the home Jose Marquez shares with his mother. (Natalie Keyssar for The Washington Post)

For Marquez, deportation meant arriving in the Dominican Republic as an unemployed man in his 40s. His Spanish was so rusty he needed classes. His immediate family lived in New York - one sister is U.S.-born, and his parents and other two siblings all became U.S. citizens in the 1990s.

Marquez founded a small company installing swimming pools, married, raised three children and divorced. All the while, he tracked U.S. news on the internet, which his brother paid for. He connected with other deported veterans to lobby American politicians to bring them back to the United States.

“I was taught to fight in the military,” Marquez said, “and that’s what I did.”

As the years passed, that fight grew tougher. Marquez’s eyesight and hearing began to fail. He needed better health care and more money, but he said he couldn’t get it outside of the United States.

After Biden took office, Marquez applied on his own to return. Officials rejected him in May 2022, partly because he had not provided enough reasons to justify his return, records show.

Once more, he needed a lawyer. He emailed Pasquarella, then at the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, and she connected him to his old lawyer, Markowitz, who was stunned.

By then, Markowitz was a professor at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in New York, teaching and supervising students as they worked on real cases. He assigned his students the task that in 2005 had seemed impossible: Bring Marquez back to the United States.

Forever.

Markowitz and his students rewrote Marquez’s parole application to provide more specifics about why he needed to return - such as getting access to higher-quality health care and caring for his elderly mother - and the government approved him for temporary entry into the United States.

A bible open on Jose Marquez’s bedroom dresser at home. (Natalie Keyssar for The Washington Post)

Then what felt like a miracle happened: The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled in September that certain state drug offenses, including Marquez’s, should not be considered aggravated felonies under federal law.

Markowitz said that ruling meant Marquez never should have lost his permanent residency - and his crimes never should have caused him to be subject to mandatory detention and removal.

Marquez still had to ask an immigration judge to overturn his deportation order, within 30 days of that appeals court ruling.

Law students Stacy Moses and Rob Cook pulled all-nighters to draft the court motion, emailing Markowitz their revisions before dawn.

Marquez returned in November and reunited days later with Markowitz at the law school in Manhattan.

Sitting in a conference room, Markowitz plunked down a piece of paper on a table between them.

“Do you understand what that means?” Markowitz asked Marquez.

“Does this mean I can apply for my green card?” Marquez asked.

“Nope,” Markowitz said. “This means you have your green card, right now, sitting here.”

Shouts and tears filled the room.

Finally, Marquez kept saying, they had won.

Of the 120 deported veterans who have returned to the United States under Biden, 30 have become citizens, according to DHS.

Marquez applied for citizenship in May and said he is also in the process of sponsoring his children for legal U.S. residency.

María Esperanza Almánzar Liriano at her home in New York. M (Natalie Keyssar for The Washington Post)

Now he shuttles between the Dominican Republic to care for his children and New York to watch out for his mother, Maria Almanzar, 85, a spitfire who cracks jokes and listens to Spanish-language prayer services on the radio. She has been diagnosed with cancer again.

In New York, he sleeps in his childhood bedroom in the rent-controlled walk-up where his family has lived for more than 50 years. Framed photographs on the wood-paneled walls remind him of the family celebrations that he missed.

Much is unfamiliar in the old neighborhood where he grew up playing stick ball. Then, the streets felt barren and dark. Now, lights brighten the avenues. The old Dominican corner store has become an organic deli.

In late January, Marquez and others who had won their deportation cases spoke to a packed room of Cardozo law students in hopes of inspiring them to represent immigrants in deportation proceedings.

One member of the panel, a nonveteran who returned after being deported, described being kicked out of the United States as “a death of sorts, a death of the life you knew, the life you loved.”

Sitting nearby, Marquez, 60, nodded, his eyes wet.

That is how it had felt, he said later, during all those years.