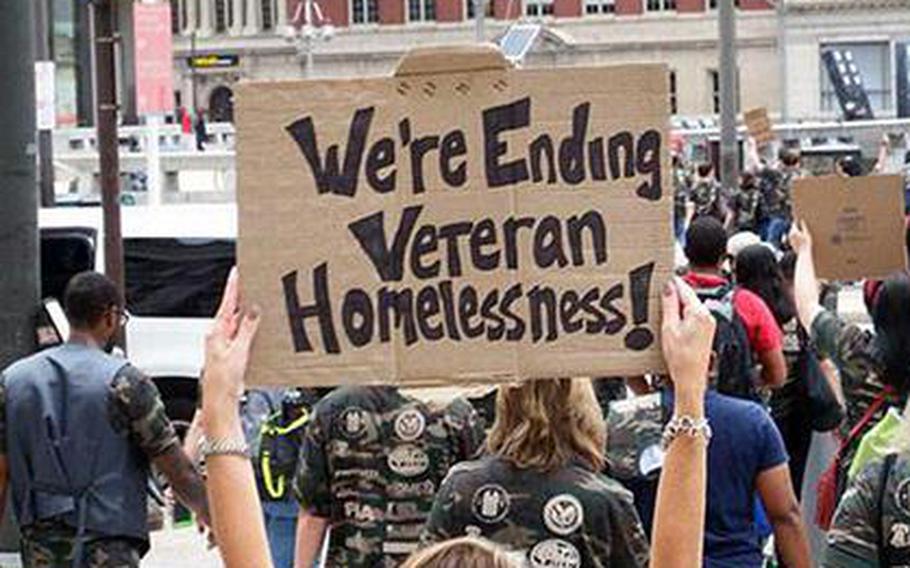

A focused approach in Los Angeles for moving homeless veterans off the streets, tearing down sidewalk encampments and providing them with assistance is yielding promising results for some but failing others, according to some veterans advocates. (Veterans Affairs)

WASHINGTON — A focused approach in Los Angeles for moving homeless veterans off the streets, tearing down sidewalk encampments and providing them with assistance is yielding promising results for some but failing others, according to some veterans advocates.

“I see veterans whose lives are changed and others who give up. This process is painstakingly long and requires a lot of accountabilities on their part. Some get tired of waiting, and we simply lose contact,” said Kyle Bush, a 38-year-old Air Force veteran who served in Afghanistan and is an outreach coordinator with the nonprofit U.S. Vets.

U.S. Vets partners with the Department of Veterans Affairs and counties across California to place veterans into long-term housing and help resolve the problems that led them to the streets in the first place.

Nearly 1,800 homeless veterans in Los Angeles County moved into subsidized apartments in 2023 after connecting with a full menu of support services, said Jim Zenner, director of the county’s Department of Military and Veterans Affairs.

Benefits spanned food assistance, grants for job training, disability benefits, addiction treatment and short-term stays at motels until subsidized housing was available, he said.

While 40% more homeless veterans found long-term housing in 2023, success is measured against a backdrop of rising homelessness nationwide, including among the military population.

About one-third of the nation’s homeless veterans live in California, based on a one-night yearly count conducted by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The number of homeless veterans in California is estimated to be more than 10,000. More than half are 55 and older. Los Angeles is at the epicenter of the problem.

There are an estimated 3,800 homeless veterans in the metropolitan Los Angeles area, according to the 2023 HUD count.

But some advocates warn the true scope of the homelessness problem is not fully understood in Los Angeles or elsewhere in the nation.

The HUD census does not account for all homeless people, including veterans, who often are hidden and out of sight – staying in their cars, sleeping on a friend’s couch or moving in and out of temporary shelters.

Kyle Bush is an outreach worker with U.S. Vets, a nonprofit that works to connect veterans with the services and benefits that they need to obtain and maintain housing in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Bush previously served as a staff sergeant in the Air Force that included a deployment to Afghanistan. (Kyle Bush)

“To say that the count is accurate is an over-simplification of a big problem. These homeless veterans can be anywhere – under overpasses, on dry riverbeds, in their vehicles,” Bush said. “This is a transient population that’s not looking for a handout.”

A major challenge with outreach efforts to secure housing is the time it takes to qualify veterans for all the services they might need -- from housing and food to mental health counseling and addiction treatment.

Many of them do not follow through.

“I resisted asking for help for a long time. I didn’t trust the system and got caught up in the day-to-day struggle of homelessness,” said Navy veteran David Crassweller, 61, who was in a construction battalion in Mississippi.

Crassweller, who has a service dog named Louie, recently moved into a subsidized apartment in Palmdale on the outskirts of Los Angeles County after being homeless for 18 months. He and his dog lived in an abandoned trailer for part of that time until it was uninhabitable, he said.

“I did not want to be eating from a can of cold tuna [while] sitting on a curb at 7-Eleven because I had no place to go,” Crassweller said about his decision to connect with veteran support services through Los Angeles.

He said he was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder related to his military service from 1985-1988.

Crassweller worked as a carpenter after leaving the service but struggled to maintain employment after losing part of his right hand in a woodchipper accident. He received help for a while with room and board from an elderly relative, who later suffered a heart attack.

.jpg/alternates/PORTRAIT_350/KIMG01592%201.JPG)

Navy veteran David Crassweller, 61, was homeless for 18 months but said he was reluctant to ask for help. (David Crassweller)

Homeless veterans often have multiple problems that need to be addressed before they can maintain long-term housing, Bush said. They might need help with drug addiction, legal problems and mental health disorders, among other issues.

Veterans who are homeless often need to be qualified for benefits and services. In some cases, they could require health care and disability compensation through the Department of Veterans Affairs or rent vouchers with HUD’s Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing program.

The process for getting services averages about three months but often takes longer, Bush said.

Bush, a former staff sergeant, said he sought to help other veterans through his job at U.S. Vets after he received assistance with his own struggles after leaving the Air Force in 2012 after six years of service.

“It’s not just the housing but also the wraparound services that keep veterans stable and make the difference. But we lose veterans in the process of trying to help them,” he said.

Bush sees his work coordinating services for veterans as an education for the former service members he helps.

“Finding my way through the LA system is not easy. There aren’t a lot of services just for women veterans,” said Babs Ludikhuize, a 62-year-old Air Force veteran who was addicted to drugs for several years after military service.

Ludikhuize, who said she has flashbacks from military sexual trauma, was an airman first class whose service was from 1979-1984, including two years in the Reserve.

She moved into an apartment building for veterans in 2023 on the West Los Angeles VA campus, less than a mile from a VA medical center, where she goes for clinical care. The campus is the future site for hundreds of housing units planned for veterans who are homeless.

Babs Ludikhuize, a 62-year-old Air Force veteran, said she became addicted to drugs after military service. She moved into an apartment building for veterans in 2023 on the West Los Angeles VA campus, less than a mile from a VA medical center, where she goes for her medical care. The campus is the future site for hundreds of housing units planned for veterans who are homeless. (Babs Ludikhuize)

But the housing seems like a far-off promise for organizations that need housing for veterans now.

“With housing prices high, I have few options right now for veterans, and many are not in desirable locations,” Bush said. “I have to say to them, ‘Hey, I got you a place, but I can’t guarantee your safety there’.”

Some landlords might not accept the HUD vouchers for rental assistance because they can charge higher prices for their units on the open market.

In March, California voters passed Proposition 1, a $6.4 billion bond measure for addressing the homeless crisis. The measure places a special emphasis on expanding housing and mental health services.

Counties are required to spend two-thirds of the funds that they receive on developing housing and providing more assistance to people with mental illness and addiction disorders.

“The key to ensuring veterans find housing and stay housed is multifaceted, which is why LA County is committed to leveraging every resource we can,” Zenner said.

The county’s $45 billion budget for 2024-2025 includes $728 million to clear homeless encampments and move people to short-term and permanent housing. The county also is introducing a master leasing program that offers veterans up to five-year leases for apartments from private landlords.

Master leases provide a guarantee that a landlord will receive full rent payment from the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, a regional agency with an $800 million budget for providing temporary shelter and long-term housing for people experiencing homelessness, including veterans.

The authority serves as property manager screening tenants and working to fill units within five days of availability.

“Master leasing offers landlords fiscal security,” Zenner said. “We are making the tenant selection and inspecting units in advance for the veteran.”

Gerson Montalban, a former lance corporal in the Marine Corps, recently received assistance through HUD’s housing voucher program for veterans.

He also was assigned a case manager to help coordinate his VA benefits, including for health care and disability compensation.

Montalban, 47, said he has been homeless since June 2023, after losing his job and separating from his wife.

“I didn’t know what to expect or the questions I needed to ask,” said Montalban, who now receives VA disability compensation for post-traumatic stress disorder and a back injury related to military service.

He served in the military from 2001-2002, with a deployment to Japan. But he said he was discharged early for medical reasons.

Montalban was provided short-term stay housing in January through a local nonprofit. He is now waiting on a subsidized apartment to come available.

“Finding a permanent place where they accept my housing voucher is taking time too,” he said.

Montalban also has had to deal with legal problems connected to his pending divorce

Crassweller said he also waited for more months for a subsidized apartment after living on the streets with his service dog. He moved to different short-stay motels with the help of a local nonprofit and county veterans services until a permanent place became available.

“The help was there. It just took a while for me to realize that I needed it – and that I couldn’t get through this on my own,” he said.