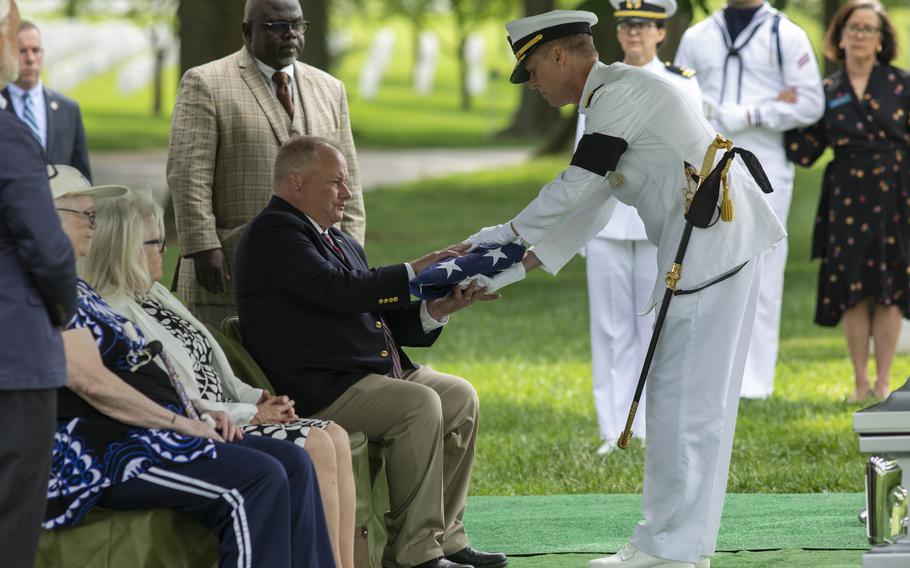

The U.S. Navy Ceremonial Guard holds an American flag over the casket of Starring Brooks Winfield in Arlington National Cemetery on May 9, 2024. (Robb Hill for The Washington Post)

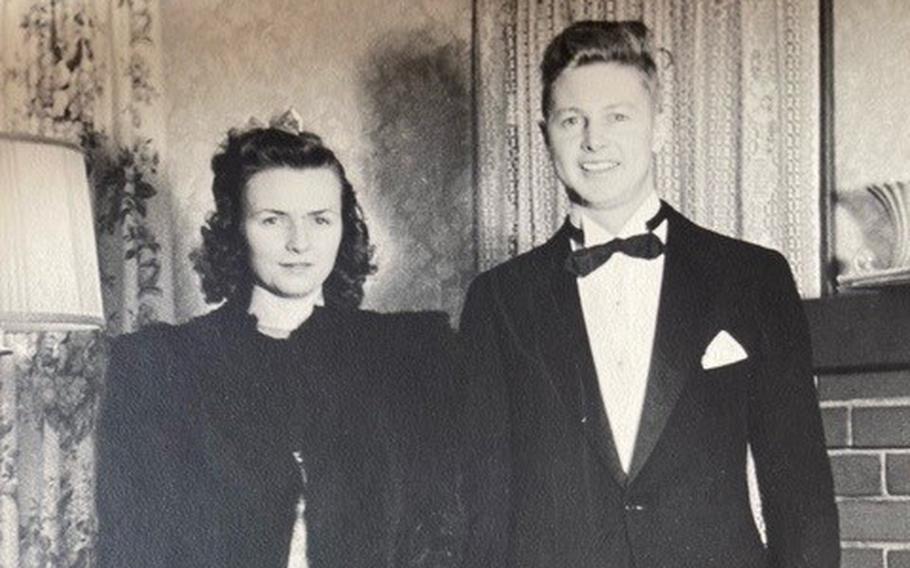

In 1940, a 21-year-old former miner from California joined the U.S. Naval Reserve. He studied to become a radio man, sending and receiving Morse code. And in September 1941, after marrying his high school sweetheart while on leave, he reported back for duty on the USS Oklahoma in Pearl Harbor.

The assignment proved fatal. He died weeks later on Dec. 7, 1941, alongside more than 2,400 people during Japan’s attack on the port. The Oklahoma remained partly submerged until 1944, when those who perished were recovered from the ship. Hundreds whose identities could not be determined were buried.

On Thursday, the radio man — identified decades after his death as Starring Brooks Winfield with the help of DNA analysis — was honored with interment at Arlington National Cemetery. Though they never knew Winfield, relatives who worked with the Navy to identify him and honor his sacrifice were on hand to say goodbye.

“This is a permanent marker at one of the hallowest grounds in the United States,” Adam Morrill, Winfield’s grandnephew, said. “We’re not leaving anyone behind.”

Starring Brooks Winfield with his future wife Gailene Beth Walker in 1935. (Winfield family photo)

At Arlington, Winfield’s casket arrived in a hearse, not far from where he would be buried under gray skies. Sitting before the casket as members of the U.S. Navy Ceremonial Guard held an American flag above it, his family listened to a chaplain recite the 23rd Psalm.

Winfield then was honored with a three-rifle volley — seven sailors firing into the air three times. The U.S. Navy Band played “Taps.” The Guard members folded the flag into a triangle and presented it to Morrill.

The chaplain said Winfield would now rest in “a place that can only be earned and cannot be bought.”

“Today, Starring takes his rightful place here,” she said.

This solemn ritual was the result of science catching up with national tragedy over the course of eight decades. Winfield was identified after his sister Meryl, or “Sunny,” submitted a DNA sample to the USS Oklahoma Project, a program that started in 2015 to identify Pearl Harbor victims. The project permitted the remains of unknown service members resting in a Hawaii cemetery to be re-examined.

Meryl died before her brother’s identification was made. Morrill became Winfield’s “designee,” the closest living relative willing and able to bury him in accord with his family’s wishes.

Adam Morrill, the grandnephew of Starring Brooks Winfield, receives the American flag during his funeral service at Arlington National Cemetery on May 9, 2024. (Robb Hill for The Washington Post)

Morrill’s grandmother often told stories about her precocious brother who, though he was two years younger, skipped two grades and graduated alongside her, according to Morrill. What remains are fragments of memories, but fragments kept alive over generations.

Winfield played basketball and football. He loved to hunt and fish. He married his best friend’s sister — and, even after Winfield’s death, the families remained close, remembering Winfield as an uncle.

At first, Morrill wasn’t sure where to bury his great uncle. Morrill considered the cemetery where his grandparents were buried in California, but it had fallen into disrepair. Another cemetery where family members were buried couldn’t accommodate relatives in adjacent plots. Morrill concluded that Arlington was a great option.

“I thought it’s a fitting permanent memorial to him after going 80-plus years without anything,” Morrill said.

Winfield comes to his permanent resting place about two years after the USS Oklahoma Project wound down.

The U.S. Navy Ceremonial Guard, with the hearse carrying Navy Radioman 3rd Class Starring Brooks Winfield, marches down McClellan Road in Arlington National Cemetery on May 9, 2024. (Robb Hill for The Washington Post)

According to Sean Everette, spokesman for the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, 394 sailors and Marines were considered still missing and unaccounted for from the Oklahoma before the program began. From 2015 to 2021, when the program ended, 362 were identified. Partly because of COVID delays, some are still being buried with military honors.

There are still more than 81,000 service members missing from conflicts since World War II, Everette said, and the vast majority are from that global conflict. Though decades pass, the armed services’ responsibility to these individuals does not fade away. And even in a new century, identifying those who died in action can bring closure.

“When service members raise their right hand and swear to defend the Constitution and the United States, the country makes them a promise,” Everette said. “It is our duty to find these people and make sure we find the family.”

Kevin M. Hymel, a contract historian with the cemetery who was at Winfield’s service, said he was not sure when another victim of Pearl Harbor would be interred there. Many of those who died on Dec. 7 were in their 20s and did not have families — but family members such as Morrill must be found to facilitate these ceremonies. Meanwhile, the attack that changed the course of the 20th century is now the better part of a century behind us.

The ceremony, however, remains the same.

“It’s been like this for decades,” Hymel said.