Malcolm Champagne, 102, receives applause from audience after Air Force Brig. Gen. Dean Sniegowski officially awarded the World War II veteran a long-delayed Purple Heart medal during a Sept. 15, 2023, ceremony in Portland, Ore. (Michael Winter/Department of Veterans Affairs)

A survivor of “Black Thursday” raid — one of the costliest American missions of World War II — has belatedly received medals that he earned 80 years ago jumping from his burning B-17 bomber and being taken prisoner by German forces for the rest of the war.

“We lost 60 B-17s that day — that’s 600 men,” recalled Malcolm Champagne, 102. “Of those 600 men, 300 survived. I’m one of those 300.”

Champagne recalled the Oct. 14, 1943, attack on the ball-bearing plants at Schweinfurt, Germany, during a ceremony last month at a senior living center in Portland, Ore.

Along with friends and family were guests from the Department of Veterans Affairs and Brig. Gen. Dean Sniegowski of 8th Air Force, the modern descendent of the bomber command with which Champagne, a lieutenant at the time, served as a navigator during World War II.

Sniegowski was on hand to officially award Champagne with medals that were lost in the post-war shuffle.

“It’s not every day you get to right a wrong and recognize a hero,” he said. “Today we award the Purple Heart to United States Army Air Corps 1st Lt. Malcolm ‘Mac’ Champagne.”

Air Force Brig. Gen. Dean Sniegowski, left, pins a Purple Heart on Malcolm Champagne, 102, for wounds received as B-17 navigator during a 1943 bombing raid over Germany, during a Sept. 15, 2023, ceremony. (Michael Winter/Department of Veterans Affairs)

Sniegowski’s choice of words underscored Champagne’s eagerness to get into World War II.

A native of Glens Falls, N.Y., Champagne was 20 years old when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, and the United States entered World War II.

“The country is in trouble, I need to go,” Champagne recalled telling his parents when he enlisted.

Commissioned an officer in December 1942, his was the last class of aviators who graduated into what was then the Army Air Corps.

By the time Champagne arrived in early 1943 in England, he was in the Army Air Force assigned to the 326th Bomb Squadron, 92nd Bomb Group.

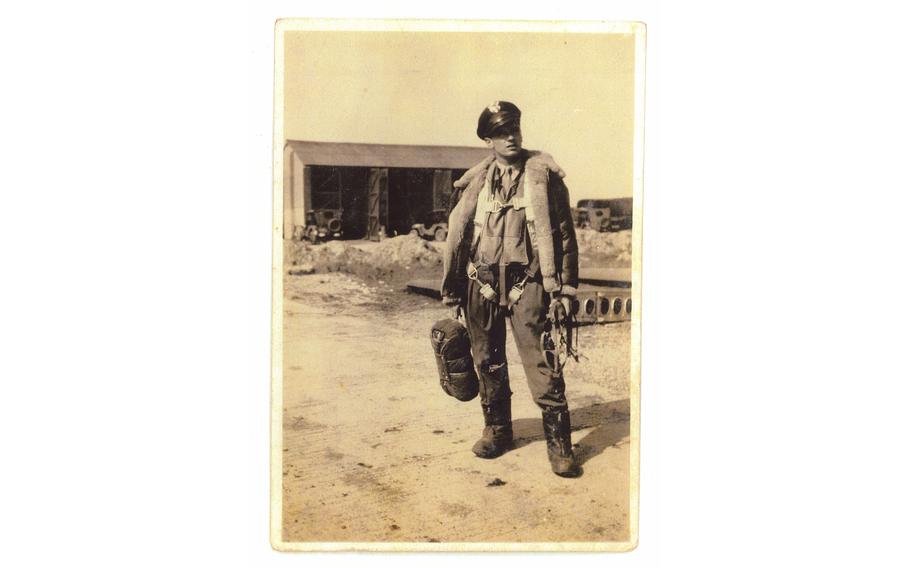

Lt. Malcolm Champagne was a 22-year-old B-17 navigator in 1943 when his bomber was shot down in the “Black Thursday” raid on Schweinfurt, Germany. Champagne, now 102, received long-overdue medals during a ceremony in September in Portland, Ore. (Malcolm Champagne)

The tide of the war in Europe was turning — American and British troops had invaded North Africa, followed by Sicily and Italy. Italy had officially surrendered on Sept. 3, though German troops held much of the northern part of the country. Soviet Union troops were pushing back German forces from Stalingrad in Russia.

But France and much of Western Europe was still under German occupation. To strike back, British and U.S. air forces kept up a round-the-clock bombing campaign.

Escort fighters of the time had a limited range of about 220 miles, allowing them to reach western Germany from England. After that, the bombers would fly on alone. British aircraft flew at night in “area bombing” missions. The Americans preferred “precision daylight bombing” to hit key targets.

Champagne was an “old-timer” by the fall of 1943, with 15 missions flown. The 8th Army Air Force had already hit Schweinfurt once — ball bearings were a crucial component in reducing metal friction in tanks, planes, and war machinery.

For the second raid, 291 American bombers took off from southeastern England, with P-47 escort fighters going as far as Aachen, a city in the western part of Germany. It was another 200 miles to Schweinfurt.

The Allied bombers would first have to withstand an attack from a wave of German fighter aircraft and then near the target’s anti-aircraft artillery.

Champagne’s B-17 Flying Fortress bomber was ripped apart from the fighters and artillery flak, destroying the high-altitude oxygen system that was their only way to breathe at 20,000 feet. Champagne jumped from the plane with other surviving crew members. Those who made it to the ground were captured by German soldiers.

Allied commanders hailed the mission as a success — 1,122 bombs dropped, 141 had landed in the factory area and 88 were direct hits — impressive numbers in an era of free-falling iron bombs.

But the cost was high. The Army Air Force reported 61 of the 291 bombers were shot down, 17 made it back to England but were total losses, and 121 required repairs that would keep them out of action for varying periods.

Of the estimated 3,000 pilots and crew that left for Schweinfurt, 600 were killed, wounded or missing in action. It was later learned about 300 had been taken prisoner by the Germans. The 20% casualty rate was double what U.S. planners had considered an “acceptable loss.”

Schweinfurt would be the last time U.S. bombers would venture so far into Germany until the new long-range P-51 Mustang escort fighters arrived in large numbers the next year.

The strategy that led to the “Black Thursday” raid continues to be studied. The American Museum of the Mighty Eighth Air Force has a presentation and discussion on the raid on Oct. 19 in Savannah, Ga. It will be posted online for later viewing.

An Army Air Force B-17 Flying Fortresses and pathfinder of the U.S. 8th Air Force, 306th Bomb Group in flight during a mission in World War II. (U.S. Air Force)

Champagne spent more than two years in Luft Stalag III, south of Berlin. The camp’s population had swelled to 7,500 Americans, 2,500 British, and 1,000 from other Allied forces by April 1945. In the closing days of the war, it was liberated by Soviet troops.

During the long months in captivity and the sometimes chaotic, long journey back to American lines, then home, Champagne had lost most of his personal possessions. In that time, the medals that he earned were lost in a tidal wave of paperwork for the troops returning from war.

In March 2023, Army veteran Fatima Safi was early in her new role as former prisoner of war advocate for the VA’s Portland Health Care System. She met Champagne’s family and asked if there was anything she could do to help them.

“Could you get him his Purple Heart?” his son Ned asked.

Getting approvals for Purple Hearts can be notoriously slow and lead to rejections because of lost paperwork, including up to 18 million records of Army and Air Force service members destroyed in a 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in Missouri. The destroyed documents covered about 80% of those who served in the Army between 1912 and 1959.

But Champagne’s capture and injuries made his case clear cut. The Army approved the Purple Heart, and the POW Medal, African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with one Bronze Service Star, World War II Victory Medal, and U.S. Army Air Force Navigator Wings.

Safi worked with military and VA officials for a special presentation in Portland on Sept. 15, POW-MIA Day.

For Safi, it is a chance to recall those who endured enemy captivity and came home, along with those who were missing in America’s wars and conflicts.

“It’s a day when our country expresses eternal gratitude,” she said.