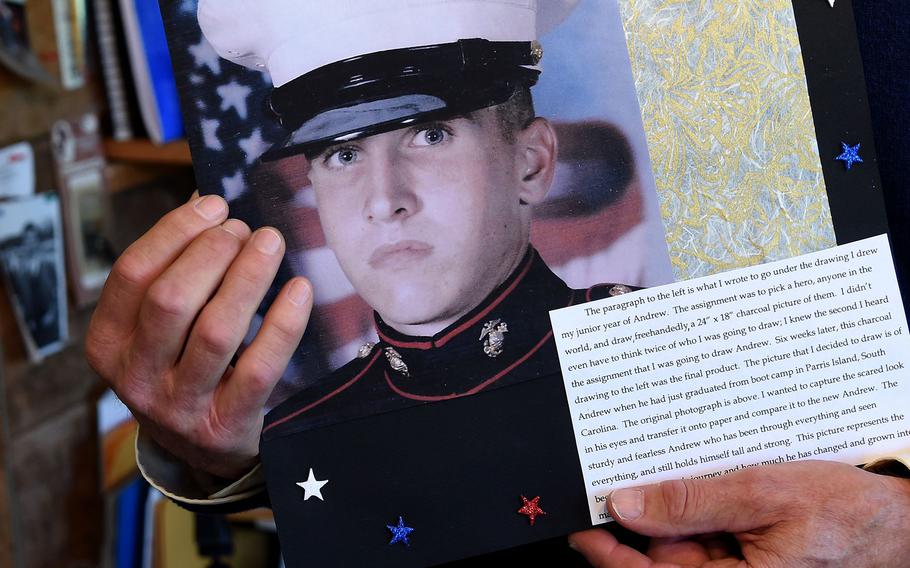

Patrick Smithwick holds a photograph of his son Andrew, who became homeless after serving two tours as a Marine in Iraq. (Barbara Haddock Taylor)

(Tribune News Service) — When Patrick Smithwick was raising his second son in the horse country of Baltimore County, Md., he had every reason to believe that Andrew Coston Smithwick would grow up to be as successful as everyone in their high-achieving family.

Andrew had a sharp mind and many friends. He was a good student and tireless distance runner at a local private school. He worked hard on the family farm, could tame difficult horses and charmed the young ladies he knew.

But things haven’t gone as the father of three hoped. Andrew Smithwick was last seen about four weeks ago, toting a heavy pack on a bicycle along a highway in New Mexico, an overgrown beard matting his weathered face. His 6-foot-3 frame appeared gaunt, his clothes dirty in the photo an internet acquaintance sent. The Boys’ Latin School graduate, 38, is one of America’s more than 67,000 homeless military veterans and 630,000 homeless people.

Patrick Smithwick, a horseman, author and retired teacher who lives with his wife, Ansley, in Maryland, tells his son’s wrenching story — and his family’s quest to find Andrew and bring him home safely — in his new book, “War’s Over, Come Home,” published by TidePool Press last month.

Smithwick didn’t relish writing “War’s Over” any more than he, Ansley, and their two other grown children, Paddy and Eliza, have enjoyed living the slow-motion tragedy it unfurls. He said it has been agonizing to recall and describe the main events.

But he wrote it with two goals in mind — to illuminate for readers the world in which America’s homeless veterans live, and to give someone, somewhere, information they might be able to use to spot the ever-moving Andrew, send the family a tip, and perhaps set in motion a chain of events that could bring him back to Maryland and give him a chance to recover.

“As a father, it’s simple — you love your children as much as you possibly can, and you remain loyal to them and stick by them no matter what,” Smithwick said days before Father’s Day, almost certain to become his sixth in a row without seeing his son. “And yes, I do believe we’re going to find him and get him the help he needs.”

Patrick Smithwick is the author of “War’s Over, Come Home” about his search for his son, Andrew, who became homeless after serving two tours as a Marine in Iraq. (Barbara Haddock Taylor)

If there were a least likely place to discuss homelessness in the United States — and in particular veteran homelessness — it might seem to be Prospect Farm, the rolling, 9-acre spread in rural Monkton where Smithwick has lived for years with Ansley, a former private-school teacher and administrator, and a menagerie of animals.

This is where Smithwick (pronounced “Smithick”) grew up the son of a legendary steeplechase rider, A.J. Smithwick, and came of age among his rough-and-tumble friends. It’s where he did his homework as a Gilman School student in the 1960s. And it’s where, decades later, he spent many happy hours teaching Andrew to ride, shoot, swim and fish.

Tall, slender and dressed in a writerly blazer, the 72-year-old author steers a guest through the family’s early-1800s main house, stopping to tell the stories behind such artifacts as framed news clippings about his famed dad and oil paintings of local equestrian scenes.

But it’s in the intimate setting of his home office, a refurbished milking parlor in the farm’s pre-Civil War barn, that Smithwick feels comfortable enough to start unpacking the story of Andrew, a lean, handsome young man with penetrating eyes who looks out from numerous pictures on the walls.

A good athlete and an even better marksman as a boy, Smithwick said, Andrew was such a gentle soul he had to ask his sister to bait his fishhooks. Looking back over the years, though, he can see there were signs of problems to come.

Struggles with organization, he said, likely brought Andrew unwelcome stress, which might have hindered his studying.

“Rebelling” — as is father put it — in his final year of high school, he failed to graduate alongside his classmates. After moving to Florida to live with an aunt, he excelled in enough of his community college classes to earn a diploma from his high school.

“Mercer Neale was an understanding man, and he had a lot of respect for Andrew,” said Smithwick, referring to the legendary former headmaster at Boys Latin.

Patrick Smithwick is the author of “War’s Over, Come Home” about his search for his son, Andrew, who became homeless after serving two tours in Iraq. Here, he stands near a portrait of Andrew that is displayed in his home on May 17, 2023. (Barbara Haddock Taylor)

After tackling a series of unfulfilling jobs, Andrew began talking about joining the Marines. He scored so well on aptitude tests that recruiters came after him. By 2004, he had been trained as an infantryman and a sniper, signed up for a five-year hitch, and found himself part of an aviation-support unit on its way to Iraq, where coalition forces had invaded the year before.

Those were not easy times for the Smithwicks. Reports coming out of hot zones like the city of Fallujah were spotty, but the news segments they saw about equipment shortages and IEDs were so nerve-wracking the family constantly felt on edge.

Andrew never shared information about his unit’s whereabouts, Smithwick said, but the family learned from letters home, and from later visits, of some of the horrors he faced — watching as a sergeant entered a bathroom facility before it was blown up, picking up body parts after an ambush, surviving a short-range machine-gun attack only thanks to his Kevlar flak jacket.

“He said you could never trust the Iraqi soldiers we trained, and you really never had any idea who was going to pull out an AK-47 and point it at you, including children,” recalled Smithwick, his voice catching with emotion. “You had to decide: ‘Do you shoot this child first, or do you wait?’ Your life was on the line in the worst of circumstances.”

No one who has studied the aftereffects of trauma can be surprised to learn — from the book or from Smithwick — how things played out for Andrew over the next few years.

Returning to the States in 2008, Andrew scored good jobs in security and trucking but couldn’t hold them, Smithwick recalled.

He drifted to Michigan to help start a pot-growing business, but it failed. After landing what he saw as a dream job — as a bus driver in Palm Springs, Calif. — he began arguing with customers, venting anger and missing work.

Between 2013 and 2017, Andrew’s anger seemed to morph into something else, Smithwick wrote in the book. Andrew told his family he believed they were multimillionaires who were withholding an inheritance he was due, that his siblings — Paddy, a dentist, and Eliza, a designer, both of whom live in Colorado ― were FBI agents watching his every move, and that most people he met were out to do him harm.

The family ultimately used legal means to gain access to progress reports from a veterans’ hospital where Andrew stayed in California. As Smithwick describes in “War’s Over,” they accessed 328 pages of records related to their son’s mental health.

About 7% of veterans — and up to 30% who served in Operation Iraqi Freedom — suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, an affliction associated with psychological problems ranging from depression and anxiety to paranoid schizophrenia, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Smithwick, whose three previous books focus on the his family’s adventures on the equine racing world in Maryland, weaves a gripping tale that introduces dozens of the colorful characters the family has met while traveling, nearly always on short notice and at great expense, to encampments, parks and alleyways where the nation’s homeless reside.

Patrick Smithwick is a horseman, author and retired teacher who lives with his wife, Ansley, in Maryland. (Barbara Haddock Taylor)

At one sprawling encampment outside Seattle, he met a vet who “perplexed me” over a course of days, he wrote, for the way he wore a blanket over his lap no matter the weather — only to see, when the blanket fell away, that the man had no legs. In San Diego, a man with an alcohol problem who had lost his job, family and home, on being shown a photo of Andrew, asked Smithwick if he could join the search.

More than once — in heavily populated encampments in Los Angeles or Orlando, Fla., or outside Santa Fe or Albuquerque, N.M. — Smithwick tells of moving gingerly through throngs of people, entering areas he has been cautioned to avoid, feeling certain he has spotted Andrew only to be disappointed when he got closer and stole a good look.

It hasn’t been all frightening. Smithwick said it has been heartening to meet so many people who are willing to help in the family’s search. Dozens of social workers, law enforcement officers, homeless advocates and newly made friends are now part of a growing informal network keeping watch for Andrew across the United States.

Some of the book’s most dramatic passages show the family actually locating a reluctant Andrew and having a brief encounter.

On one occasion, in Florida, he denied knowing them, cursed them out and disappeared. On another, in New Mexico, the family watched as he prevailed on police to drive him away.

That was one of numerous times authorities have acted to protect Andrew’s right to independence over what Smithwick believes would have been better for his son’s health, he said, though he conceded it’s difficult for police to make calls in such cases.

“It’s a fine line [authorities] have to walk between protecting the person’s rights and doing what might be best for him,” he said, choking up a bit once more. “That can be very painful.”

Smithwick devotes a lot of energy these days preparing himself for the day when the stars align for a reunion with Andrew.

Books on his shelves range from “The Body Keeps The Score,” psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk’s classic on trauma recovery, to military psychologist Glenn Schiraldi’s “PTSD Sourcebook.” He rattles off descriptions of successful new programs that offer therapy for veterans through filmmaking, theater and equine activities.

At least one expert said his optimism is not misplaced. Erin Fletcher is director of the Warrior Care Network, a mental health program of the Wounded Warrior Project that offers a range of similar therapies for both veterans and their families at four major U.S. hospitals, all free of charge. She said knowledge about treating PTSD has grown exponentially over the past 20 years, and that if affected vets can simply find ways to reach out, their odds of improvement are high.

“This is a much more hopeful time,” she said.

That, Smithwick said, is one reason he has not given up on Andrew, no matter the financial and emotional costs. He can all but picture the day his son will cross their threshold again and be prepared to start his life anew.

“We’ll never stop searching,” he said.

©2023 Baltimore Sun.

Visit baltimoresun.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.