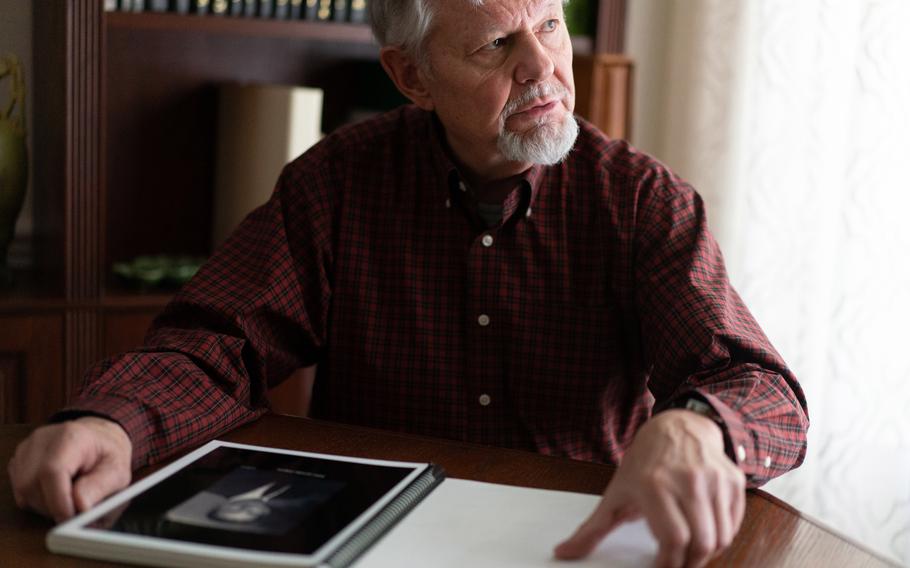

Charles Simpson, holds a photo of his uncle, James. Simpson didn’t know much about how James died until January when he read an article in The Washington Post. (Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post)

For decades, Charles Simpson's family didn't know much about how his uncle James died near the end of World War II.

James' death seemed like a cruel twist of fate. The Arkansas soldier was captured in France in 1945, then liberated from a German prison months later. While waiting to return to the United States, the Simpson family was told, he was accidentally shot by a U.S. military police officer trying to break up a fight between two Black soldiers.

From time to time, Charles said, his family tried to learn more. But they were denied access to court-martial records of military police involved in the shooting. And they were told that James' service record was destroyed in a fire.

Then, Charles read a January article in The Washington Post about two Black soldiers shot in northern France near the end of the war for asking white women for doughnuts. He realized his long-dead uncle was a victim too — the third casualty of a racist incident in a segregated Army.

"It's been a revelation," Simpson said. "This was basically a hate crime. James was in the middle of it through no fault of his own."

The deaths of Black soldiers Allen Leftridge and Frank Glenn at Camp Lucky Strike in France, about 120 miles north of Paris, were not widely documented beyond Black publications. According to news articles and a witness, the men had done nothing more than talk to French women serving U.S. soldiers coffee and doughnuts in a Red Cross tent.

Library of Congress archives, including pleas from civil rights advocates and letters from one of the Black men's widows seeking military benefits, showed how white U.S. soldiers fighting fascism abroad brought racism overseas. Even today, the Leftridge family continues to fight for a pension that they believe they are due.

Now, Technical Sgt. James L. Simpson is part of the story.

Charles Simpson, who never knew his uncle, has pieced together a scrapbook about his life from family photos, newspaper clippings, James' letters and his own mother's stories.

Charles Simpson, 77, at his home in Silver Spring, Md., looks through a scrapbook about his uncle, Technical Sgt. James L. Simpson, who was killed in France on May 22, 1945. (Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post)

James was born in 1916 on the family homestead in Cave City, Ark., according to Charles's research — the youngest brother in a family of 10. The family grew watermelons, and James studied agriculture at Southeastern State College in Oklahoma, graduating in 1941.

But war came. James joined the Army in 1942 and landed in France in November 1944, about five months after D-Day.

"Mother, please don't let yourself worry over us boys because the war can't possibly last over 6 months," he wrote that month. "And then we will be coming back home shortly after."

James's prediction proved wrong. In January 1945, he was captured on a patrol during which he "found himself looking into a machine gun in the hands of the enemy," according to one newspaper account.

After months in a prison camp, however, James was liberated — and found himself at Camp Lucky Strike near the doughnut line where three soldiers would die on May 22, 1945.

At first, the Simpson family got few details about a shooting. A letter from the Army in June 1945 indicated only that James had died of "non-battle wounds." More details came in September 1945 in a letter from a camp chaplain.

"Two soldiers started a fight in the line and two Military Policemen were called to stop the fighting," the chaplain wrote to the family. "One of the soldiers became very abusive toward the M.P. and drew a knife and was about to stab him. The other M.P. drew his revolver and was planning to fire a warning shot but instead the revolver went off as he was removing it from the holster and the bullet struck Sgt. Simpson."

The chaplain added: "I know that his death seemed so unnecessary especially having gone through the war and being so near going home."

Further correspondence indicated that the soldiers involved in the shooting were cleared in court-martial proceedings. The Simpson family, according to Charles, tried to get copies of the court-martial but were "stonewalled."

"My parents and grandparents went to their grave believing he was killed because two Black soldiers got in a fight and a white MP broke it up," he said.

That story contradicts the reporting of Alfred A. Duckett, a Black war correspondent who served in Leftridge's regiment and later became a speechwriter for the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

"When a white MP ordered him not to stand there talking to this woman, Allen turned his back on him," Duckett, who died in 1984, told oral historian Studs Terkel. "He was shot in the back and killed."

The Army and the National Archives, which maintain military records, could not immediately provide further information about Simpson or this incident.

James' widow was able to get a pension, Charles said. However, the descendants of Allen Leftridge, one of the Black soldiers killed in the shooting, are still working to secure compensation — which was wrongly denied after that death was designated "not in the line of duty," they claim.

Such designations have been reversed before, possibly clearing the way for benefits to be awarded. Just last year, for example, the ruling was reversed in a 1941 case in which a Black soldier was killed by a white policeman after talking loudly in a bus.

Will Holman, Leftridge's great-grandson, said the family has retained a lawyer and is waiting to hear back from the Army. And they want to know about more than money. Holman has one question: Does someone know who shot his ancestor?

"They should be able to find that out. If not, it's some type of coverup," he said. "There has to be some type of paperwork. … Their names should be exposed."

Charles Simpson wants those names as well. He wants the record corrected — not just for his uncle, but for history.

"This is the real story," he said.