Retired Navy pilot Everett Alvarez Jr. talks Wednesday, May 10, 2023, about his time as a prisoner of war during the Vietnam War. Alvarez was the first fighter pilot shot down during the conflict. (Ken-Yon Hardy/Stars and Stripes)

ROCKVILLE, Md. — The passage of almost 60 years has done nothing to dim former Navy fighter pilot Everett Alvarez Jr.’s memories of the night that he was shot down in the South China Sea and began what would be the second-longest period of captivity for an American service member in the Vietnam War.

At 85 years old, Alvarez still vividly remembers his Douglas A4 Skyhawk filling with smoke and coming apart as he had just a few seconds to make a series of life-or-death choices.

“I was really low. I knew I had to get out right there,” he said Wednesday in an interview at his suburban Washington, D.C., home. “I was trying to get altitude, I was trying to get out to the sea [away from the North Vietnamese coastline], I was trying to maintain control, but I couldn’t do it.”

Then a lieutenant junior grade, Alvarez made one final radio transmission to his wingmen from the USS Constellation before he hit the ejector seat and bailed out into the stormy darkness on Aug. 5, 1964 — only three days after the Gulf of Tonkin incident that triggered America’s full-scale entry into the war.

“I’ll see you guys later,” he told them.

Alvarez would ultimately spend 8½ years as a prisoner of war — much of it in the infamous “Hanoi Hilton.”

He was the first American to be shot down over North Vietnam and the first to be taken prisoner there. This week, he’s also among many veterans who are being honored with a “Welcome Home” celebration on the National Mall by the Vietnam War Commemoration to remember the 50th anniversary of the end of U.S. involvement in the conflict.

Only Floyd James Thompson, an Army Special Forces officer advising the South Vietnamese, was imprisoned longer. He was captured in South Vietnam on March 26, 1964 — more than five months before the Gulf of Tonkin incident — and held for nearly 10 years. He died in 2002.

From pilot to prisoner

Alvarez said it’s a miracle that he ejected and made it to the ground alive. Just another second or two in either direction, he said, would have brought certain death.

“I timed it pretty well,” he said, then revising that assessment. “I didn’t time it pretty well. God timed it pretty well. I figured someone is watching over me.”

Even after ending up in the gulf, still alive, Alvarez said he was then immediately met by gunfire from armed fishermen on the water.

“[They] told me to put my hands up in the air, which I did,” he said. “And they got me, quickly.”

About a week later, Alvarez found himself in Hoa Lo Prison — now infamously known as the “Hanoi Hilton,” a large complex built by colonialists to house political prisoners when the region was known as French Indochina.

“I could hear the clanking of the big gate that opened up into the prison as we drove in. I was still blindfolded and they led me into a room where that was my first living quarters. … It was a barren room, a little table, about a 10 feet by 12 [feet] room. They had a metal frame with a slat, a board, which would be the bed.”

Given nothing but a straw mat and a pillow, which was just a straw bundle, and a mosquito net, Alvarez began serving what would turn out to be more than 3,100 days of continuous captivity by the North Vietnamese.

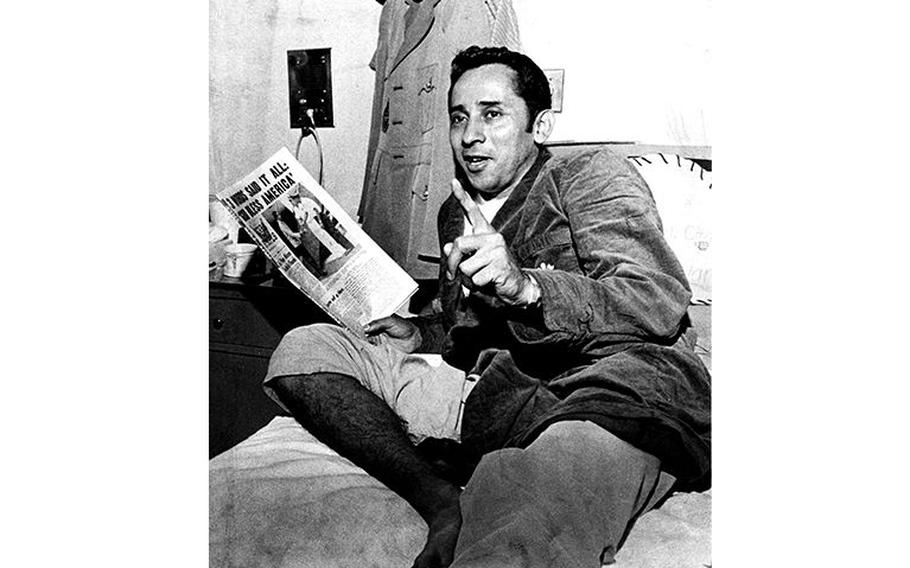

Former POW Everett Alvarez Jr. reads a copy of Stars and Stripes as he relaxes in the hospital after his release from the Hanoi Hilton in 1973. (Defense Department)

During those days, Alvarez said he was often moved over to different parts of the prison complex, and sometimes he was moved away from the complex and into the forest. At times he had roommates, and other times he didn’t. Sometimes his captors could be benevolent, and other times they were just violent.

“I told them as little as I could,” he said. “They quizzed me for six weeks to learn everything they could.”

Late in 1965, his captors moved Alvarez and other captured Americans to a group of small huts somewhere outside Hanoi — a period that the naval aviator called the “second phase of his POW life.” After several weeks, they were sent back to Hanoi and cycled through locations the POWs called “the zoo” and “the briar patch.”

At one point in 1966, the North Vietnamese marched Alvarez and several other captive Americans through the streets of Hanoi, then the capital of North Vietnam. Alvarez said “the Hanoi march” began what might have been the most hostile period of his detention, one that would last for three years.

“Things were starting to turn rough by then. After the march, things really got rough,” he said. “They would punish us. They would torture us for propaganda.

“About three years of constant punishment, torture, different things, they weren’t having success converting us to their ideology, and so they really went after us for propaganda purposes — statements, letters, tapes.”

The tough treatment of Alvarez and the other POWs continued through the next few years, especially after an escape attempt. That treatment included malnourishment, which gave Alvarez dysentery and reduced him to a little more than 100 pounds.

During his time in captivity, Alvarez said there were so many unknowns that he basically had no choice but to hang on to the few morsels of motivation he could muster — thoughts of home, trust in his faith and confidence in his country.

“It was a battle. You have got to hang on to your values, you have got to hang on to your ideals, you have got to hang on to, you know, you’re a member of a team, a group. Everybody was in this thing to keep resisting,” he said.

It was about that time that Alvarez received what was perhaps his worst injury, and one that still causes him trouble today. One of the guards flew into a rage and swung the butt of his rifle into the left side of Alvarez’s face.

“To this day, that’s why I have difficulty. It dislocated my jaw,” he said, also noting he sustained a variety of other injuries that required surgeries on both arms and his back.

Another thing that kept him and the other American POWs going during those dark years in captivity, he said, was communicating with each other. Sometimes they scribbled messages for each other on the bottom of their dishes, and other times they spoke to each other via a finger-tapped communication code.

Going home, finally

The constant interrogations and punishments for Americans at the prison would go on for a couple more years before Alvarez finally began to see some light at the end of the tunnel for him and the others at Hoa Lo.

President Richard Nixon famously increased bombing in North Vietnam in 1972, which included the Hanoi area toward the end of that year. They are often referred to as the “Christmas bombings” and one of the goals of that strategy was to push North Vietnam to the bargaining table.

Scholars and historians have debated for decades how successful Nixon’s strategy was, but Alvarez said when he heard the intensity of the American bombs exploding around him, he knew that the end of the war was in sight. He also knew something was afoot because the POWs’ living conditions began to improve, which is a common bargaining strategy often seen at the end of modern conflicts.

Navy pilot Everett Alvarez Jr. speaks to reporters at Travis Air Force Base, Calif., in February 1973 after his return from Vietnam. (Phillip M. Porter/U.S. Navy)

“We knew [North Vietnam] couldn’t last long,” Alvarez said of the relentless U.S. bombing in the latter part of 1972. A couple of weeks later in January 1973, Alvarez said he and the other American prisoners were told they were finally getting released.

“They said, ‘You will be going home soon,’ ” he said.

On Jan. 27, 1973, U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War ended with the signing of the Paris Peace Accords and officials on both sides began planning for the release of the POWs.

“We were anxious to go,” Alvarez said.

Escorted by their guards to a nearby landing strip on Feb. 12, Alvarez and dozens of other American POWs stood on the tarmac and watched as their plane — a Lockheed C-141 Starlifter — swooped in to pick them up and take them to a U.S. base in the Philippines. Alvarez was the first one called to board the plane.

“What I remember the most is the plane started up and we were taxiing, and we got to the end of the runway … we lifted off and everybody let out a big cheer,” he said. “And we toasted each other with a little Coke or soft drink that we had and said, ‘We made it.’ ”

Upon arrival in the Philippines, Alvarez was the second one off the plane — after the senior-ranking officer of the group — and he was told he’d have an opportunity to say a few words to the waiting crowd and a row of television cameras.

“I have to tell you, I was just amazed at the crowd and the attention,” Alvarez said, noting he’d heard about the rising anti-war movement in the U.S.

“I came down the ramp and I had no idea what I was going to say. But there’s [an] admiral … at the bottom of the steps. I gave him a salute and I said, ‘Lt. j.g. Alvarez reporting back, sir.’ ”

That moment was captured by a photographer and displayed on the front page of the Feb. 14, 1973, edition of Stars and Stripes.

After his return and recuperation in 1973, Alvarez went on to several different enterprises. He retired from the Navy in 1980 and subsequently served a few political appointments for President Ronald Reagan for the remainder of the decade, including deputy director of the Peace Corps and deputy administrator with the Department of Veterans Affairs.

He became a lifetime member of the Board of Fellows at Santa Clara University in California — his alma mater — and founded the information technology consulting firm Alvarez LLC about 20 years ago. The firm is still active in federal government information technology — and Alvarez is still chief executive. His son Marc is president of the company.

Alvarez has also written two books about his experiences in Vietnam, received numerous medals from his time in the Navy and might soon receive the Congressional Gold Medal, which lawmakers are now considering.

“What’s the status on that?” he asked with a smile.

As he now prepares to be honored at the Welcome Home Celebration in Washington this weekend, the proud American grandson of immigrants from Mexico points to several things that have allowed him to be successful in serving his country and realizing the American Dream.

“Everything I’ve done, I’ve just had a lot of support. I think I’ve been successful in most things I’ve tried to do. I’ve graduated in electrical engineering from a college. I became a Navy pilot. I was a political appointee. I got into the business world,” Alvarez said. “I was nothing special. I’m just one of the guys that had to do what we had to do. And that’s how we did it, one day at a time. I had a lot of discussions — a lot of conversation with the man upstairs. That’s what worked for me.”