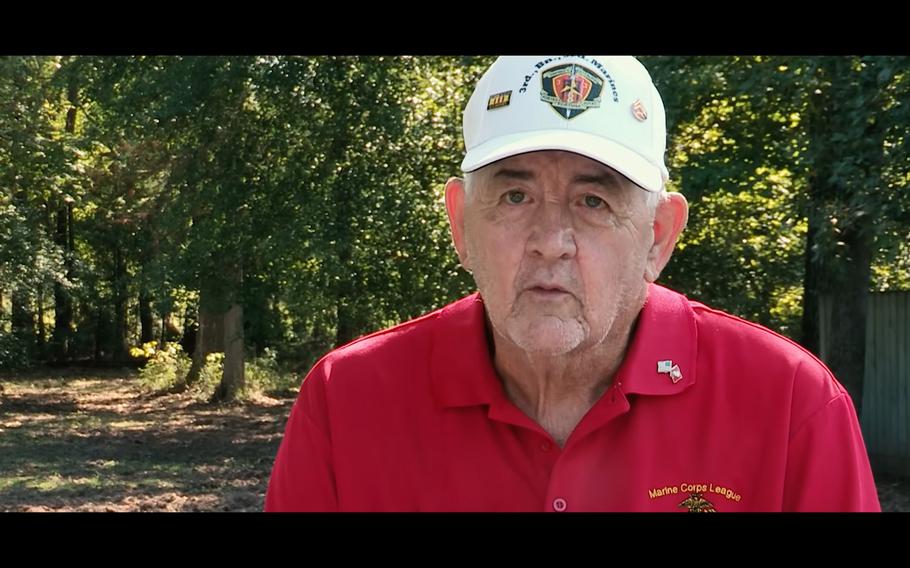

Charles Armitage, 72, served in the Marine Corps during the Vietnam War and was wounded in combat in 1968. His dog tags were removed, and about 30 years later, a stranger from California found it in Vietnam and returned it to the veteran. (Department of Veterans Affairs/screenshot from video)

Charles Armitage can easily remember the date his heart stopped beating during the Vietnam War — March 25, 1968. It was his mother’s birthday.

A Marine Corps infantryman assigned as the machine gunner for Mike Company, 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marine Division, he was stationed near the Demilitarized Zone when the troops took incoming mortar fire in the morning. Shrapnel struck Armitage in the lower chest.

“One corpsman came by and said I was dead, so he ‘toe-tagged’ me. My platoon corpsman came by and said, ‘He ain’t dead until I say he’s dead,’ ” recalled Armitage, now 73 and living in Conroe, Texas.

The medic got Armitage’s heart beating again and rushed him out for emergency surgery.

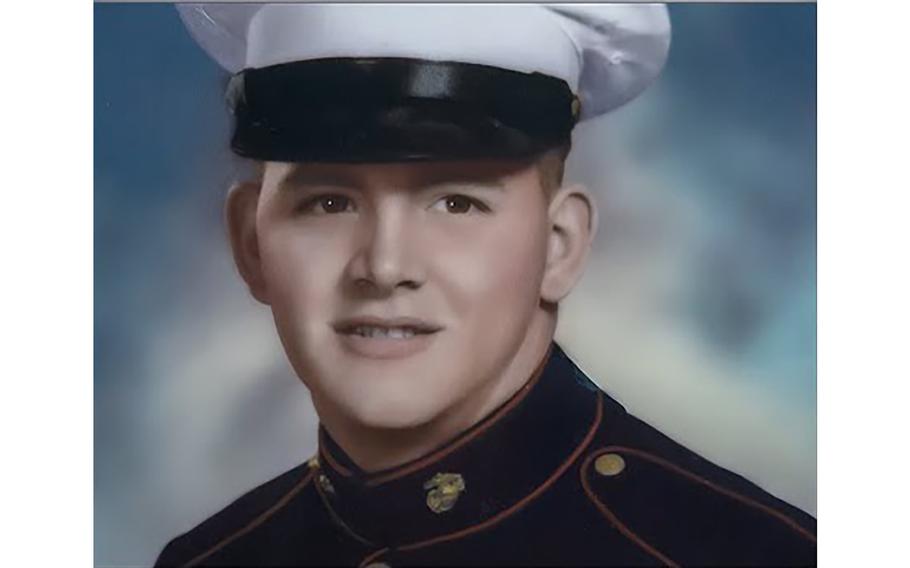

Charles Armitage served in the Marine Corps during the Vietnam War and was wounded in combat in 1968. Now 72, he lives in Conroe, Texas. (Department of Veterans Affairs/screenshot from video)

That was 55 years ago, yet the veteran still gets emotional thinking about the corpsman who saved his life while so many others didn’t make it back home. The U.S. became involved in Vietnam in 1955 to protect the country’s south from falling into communist control by the north.

The United States withdrew all combat forces in 1973 and South Vietnam collapsed two years later.

During the war, 40,934 American troops died in combat, with 11,501 of those losses coming from the Marine Corps, according to the Defense Department.

“A lot of young men and women did not come back,” Armitage said in a video produced by the Department of Veterans Affairs in honor of Vietnam Veterans Day on March 29. “That’s why if I see a veteran, young or old, I tell them, ‘Thank you for your service.’”

Armitage had hoped to make a career of the Marine Corps — his dream since he was 5 years old — but the injuries he suffered damaged his lungs, and he could no longer meet the standards for running three miles. Instead he left the service in 1972 and went into construction. After moving to the Houston area he married Pam, and became a father to her three children.

About 30 years after his time in Vietnam, a woman from California brought Armitage right back to the day he was nearly left for dead on the battlefield.

During the corpsman’s efforts to restore Armitage’s pulse, he’d cut off Armitage’s uniform, including his dog tags. One of the identification tags traveled with Armitage to surgery and the second was lost.

Stacey Mitchell, then a 30-year-old firefighter in San Jose, Calif., visited Vietnam in 1999 and while looking through the gift shop of the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City, formerly Saigon, she saw American dog tags for sale. She thought it was wrong to see them there instead of home with the troops who wore them.

“I bought them all,” she said.

Charles Armitage, 72, served in the Marine Corps during the Vietnam War and was wounded in combat in 1968. His dog tags were removed, and about 30 years later, a stranger from California found one of them in Vietnam and returned it to the veteran. It now hangs in his home alongside other reminders of his military service. (Department of Veterans Affairs/screenshot from video)

Mitchell began going into shops across the country and buying up any dog tags she could find. On a second trip to Vietnam in 2004 she did it again. In all, she estimates she bought more than 1,000.

On her days off, she began tracking down the names of troops on the tags to see if she could mail the tags back to them.

“I really had a tiny little window of time to make the person on the other side realize I was real and legit and that there was nothing fishy or weird,” Mitchell said.

When she found a veteran willing to talk, she heard all kinds of stories.

Some said they would hand them out to Vietnamese kids in the streets, or had lost them while playing volleyball or swimming. One man said he was in the shower when he got the call to move out and left his tags behind. Most said they never thought much of losing them because it was easy to get replacement tags.

“I’m just so glad I did it when I did it,” she said, becoming emotional about the memory. “The guys who got it back, I could just feel how much it meant, and that's what it was all about.”

When Armitage received his tag in the mail from Mitchell, he cried.

“I opened the envelope up, and the dog tag fell in my hand. I lost it,” he said.

Armitage’s wife Pam said she made sure to send Mitchell flowers in return.

Charles Armitage’s medals he received for service in the Marine Corps during the Vietnam War hang in his home in Conroe, Texas. (Department of Veterans Affairs/screenshot from video)

The dog tag is now framed in a shadowbox with Charles Armitage’s service photo and medals. It’s become a jumping point for the couple’s nine grandchildren to ask questions and learn about the military service of their grandfather, whom they call Pops.

Now retired, Charles Armitage has returned to his service roots, this time as a volunteer for several organizations in Conroe, which is about 50 miles north of Houston. He volunteers for the Marine Toys for Tots as well as God’s Garage, a nonprofit that donates cars to single moms, widows and military spouses of deployed troops, and the food pantry at the city’s Community Assistance Center.

He’s also part of the Marine Corps League and Pam is in her fourth year as chairwoman of the local detachment’s annual ball.

Charles Armitage said he spends this retirement this way to be in service to his community. It’s not far from the reason he gave for serving in Vietnam.

“I didn’t do it for myself,” he said. “I did it for my fellow countrymen.”