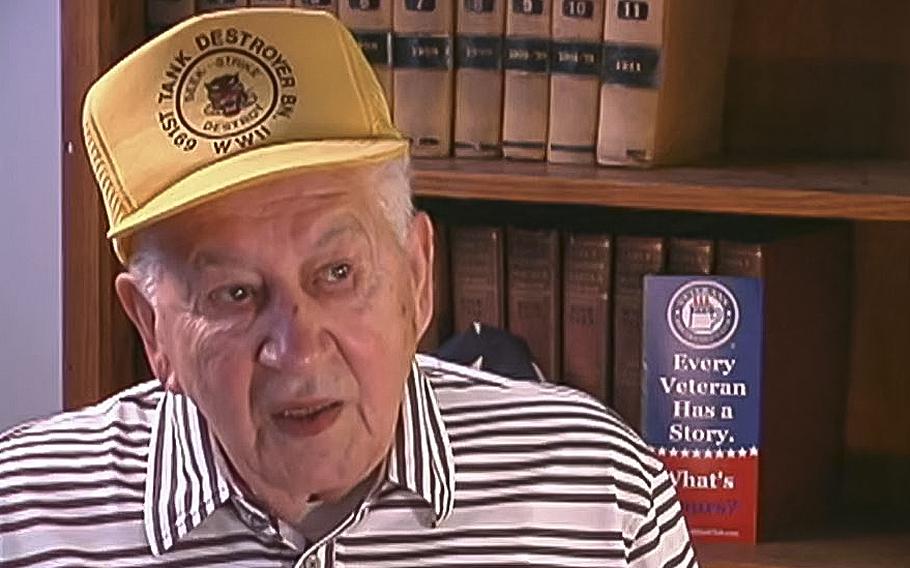

A video screen grab shows WWII veteran George Tita telling of his war experiences during an interview in June 2013. (The Social Voice Project/Vimeo)

ANNAPOLIS, Md. (Tribune News Service) — When George Tita was drafted at 18, briefly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, he did his first training stint at Fort George G. Meade.

Many of his peers cried the first night at the base — fearful teenagers, separated from their families, soon to trade textbooks for Tommy guns, knowing they may not live to see the end of the war, get married or have kids or grandkids. Tita, however, was thrilled to leave his small western Pennsylvania steel mill town and have an adventure.

“I wanted to go,” Tita said. “Being in a small town there’s no really big excitements, now was a chance to go into an outfit and see a lot of excitement.”

Excitement was certainly ahead for Tita, who will turn 100 on March 16. The Annapolis resident swears a guardian angel was watching over him during his time in the 691st Tank Destroyer Battalion in the European Theater. He can’t fathom another reason he should have so many near misses — metal projectiles inches from his skull, foxholes dug just large enough and comrades awakening him from hypothermic hallucinations — and live to tell the tales to his wife, four kids, seven grandkids and six great-grandkids.

Tita’s fateful journey began with several months of stateside training where he learned to build bridges and pillbox huts, before being assigned to one of the war’s first tank destroyer units under Gen. George Patton’s Third Army.

In the spring of 1944, the tank destroyers were set to arrive in France. That’s where Tita experienced his first lucky break.

“He was supposed to be the first wave at Normandy and the orders got mixed up,” said Tita’s granddaughter Jennifer Barber.

Tita remained in the states for another few months, missing the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944, during which an estimated 29,000 Americans were killed and 106,000 were wounded and missing.

Once Tita got to Europe, his role was reconnaissance. He was to look out for German tanks and alert his team of their location. He said he spent many lonely hours in the middle of nowhere, far from his team. He also spent a lot of time in foxholes, often with his childhood friend, Peter Primerano, who was drafted with him.

Many times the foxhole was the only thing between Tita and death as artillery shells fell around him.

“I had one explode right alongside my hole. I knew this was coming. I says, ‘Oh my God. This one has my name on it.’ You can tell by the sound of them when it’s coming, like a train coming,” Tita said. “I says [to myself], don’t go more than two steps away from your hole. I went three steps. Big mistake.”

Tita leaped into his hole, the shell exploded alongside it and a piece ricocheted off his helmet.

Another time in a foxhole, a piece of shrapnel skinned the top of his ear.

Others weren’t so lucky, like Tita’s lieutenant who popped out of the foxhole for a moment to check on things and was killed by a piece of shrapnel.

“We’re hollering at him, ‘Lay down, you dumb fool. Lay down.’ He said, ‘I’ll be all right.’ He’s on one knee. Kneeling on one knee,” Tita said. “He caught a piece of steel in this throat.”

In December 1944, Tita and his crew were sent to assist at the Battle of the Bulge, a major turning point of the war when the German military attacked the allies in the Ardennes forests in Belgium, Luxembourg and France. Counterattacks from the allies ultimately led the Germans to withdraw.

In his journey to the battle, he was driving an armored car near the Swiss-French border north to Bastogne, Belgium. Temperatures were bitterly cold and the car had no heat or windshield.

“I got the kid next to me. I says, ‘You have to drive.’ He says, ‘I never drove this.’ I says, ‘You’re going to learn right now,’” Tita said. “I’m freezing to death and I said I cannot drive anymore. I have no feeling in my foot, my arms and my hands. I have no feeling. I can’t go on.”

Once they switched spots, Tita dozed off. He dreamed of a large room with a toasty fireplace.

“I was in a big white room and saying, ‘Thank you God, I’m so warm.’ One of the lieutenants woke me up,” Tita said. “Had they not stopped when they did, I would not be here.”

When the war ended, Tita went to see a nearby concentration camp get liberated, but he couldn’t bring himself to go inside as the stench from the dead bodies was so strong. Even in the midst of the events, Tita knew the freeing of these prisoners was something historical.

“It was so filthy, so filthy,” Tita said. “Those people were human beings. Now they’re skin and bones and they never had a bath. ... I said to myself, ‘How could anybody treat people that bad?’ “

Tita returned to the states and worked in intelligence. Soon after, he met his wife Anne and started his own business, Tita Machine and Tool, making weaponry pieces including parts for the Polaris Missile, the U.S. Navy’s first submarine-launched ballistic missile.

For most of Tita’s life after the war, he lived in his hometown of Koppel, Pennsylvania. He moved to Annapolis about five years ago to be closer to his daughter, Marian Soriano, who had moved there in 1985. .

Those in his family who live in Annapolis are happy to be near him and listen to Tita’s tales.

“I’ve been listening to his war stories since I was five and I loved them,” said Soriano, 72, who remembers staying up late with her dad, watching black-and-white war movies and musing about his time in Europe.

Soriano said Tita was always very involved in his kids’ lives and helping around the house. He even gained some domestic skills like cooking, in the military.

“I’ve always been impressed with my dad. I call him a renaissance man. He was doing things that other people weren’t like, really, in the 50s, men went to work. They didn’t really pay attention to their kids and, oh my god, he was a hands-on father,” Soriano said.

Barber, Soriano’s daughter, so idolized her grandfather she requested to get her hair cut short to look like him as a young girl. Both generations get choked up thinking about how grateful they are to have had him for so long.

“Everybody just loves him,” Barber said. He’s been my hero since I was a little girl.”

Tita’s wife, Anne, and his hometown friend and wartime comrade Primerano died about 20 years ago. However, Tita continues to survive. Whether that longevity is because of a sense of stubbornness as described by Soriano, his strong Christian faith as a member of the Carpatho-Russian Orthodox church or his guardian angel continuing to watch over him, his family is simply glad to have him around.

©2023 The Capital (Annapolis, Md.)

Visit The Capital at www.hometownannapolis.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.