Vietnam veteran and retired Army Col. Paris Davis looks out and thanks the audience as he is applauded moments after receiving the Medal of Honor from President Joe Biden during a ceremony at the White House on Friday, March 3, 2023. (Carlos Bongioanni/Stars and Stripes)

WASHINGTON — President Joe Biden said Friday that there is only one word to describe former Army Col. Paris Davis — “gallantry.”

“It’s not much used these days,” Biden said at the White House, just moments before he bestowed the former Special Forces commander with the Medal of Honor. “But I can think of no better word to describe Paris.”

Biden used those words to open a ceremony in the East Room to recognize Davis’ heroics in battle with the nation’s highest military honor, nearly 60 years after the retired Green Beret boldly engaged enemy troops and rescued several wounded soldiers amid a bloody fight during the Vietnam War.

Davis, now 83, was a commander in the 5th Special Forces Group in June 1965 when his unit came under almost constant enemy fire for many hours near Bong Son on Vietnam’s southeastern coast. They had just carried out a pre-dawn raid on a North Vietnamese army camp in the area on June 18. But by the time the sun came up, they found themselves under full enemy attack and were trying to evade a constant barrage of bullets and artillery.

“Within minutes, the jungle lit up with enemy fire,” Biden said in his remarks at Friday’s ceremony, with Davis seated to his right. “[Then-]Capt. Davis rallied his team to fight back — getting so close to the enemy, he was battling them hand-to-hand.”

One by one that day, soldiers in Davis’ unit were hit with enemy fire and laid wounded in a rice paddy in Hoai Nhon District in what was then South Vietnam. Without air support and because he was the last soldier in the unit standing, Davis said it was his duty to find his men and get them to a medical helicopter.

It took several attempts for Davis to reach the wounded troops, constantly dodging enemy fire. As he ducked in and out of cover, Davis was shot in the arm and leg — but his wounds didn’t deter him. He said it wasn’t the Green Beret way.

Then-Capt. Paris Davis poses for an official U.S. Army service photo, circa early 1960s. (U.S. Army)

“Blood was everywhere,” Davis, who was also an Army Ranger, recalled in an interview Thursday. “You could smell the sweetness of blood.”

Several American troops were lying in the rice paddy, Davis said, including a sergeant and a medic. Once Davis managed to get the wounded men to the rescue helicopter, his colonel ordered him to get on the chopper.

“Sir, I’m just not going to leave,” was Davis’ response, Biden said. “I still have an American out there.”

Davis got back to the wounded medic, and the frightened soldier asked Davis if he was going to die. Davis said his answer was brief and firm: “Not before me.”

Davis recalled he wasn’t concerned about his own well-being as much as he was concerned about other U.S. troops in harm’s way.

“What you’re trying to do is stay conscious, stay mission-oriented and help where you could,” Davis said. “It wasn’t one of those things when you think, ‘I’m bleeding.’ It’s one of those things when you say, ‘I can still move.’”

After almost 20 hours of fighting ended, Davis had rescued every wounded American soldier.

“Every single one,” Biden said.

The idea of Davis getting the Medal of Honor was first mentioned by his comrades on the battlefield that day in 1965. But it would take decades for the honor to happen. Twice his nominating paperwork — a package documenting a recipient’s worthiness for the award — was lost at the Pentagon somewhere during the process. It wasn’t until just a few years ago that it regained traction, due to people who knew of Davis’ heroism — such as fellow soldier Ron Deis — and lobbied top Pentagon officials.

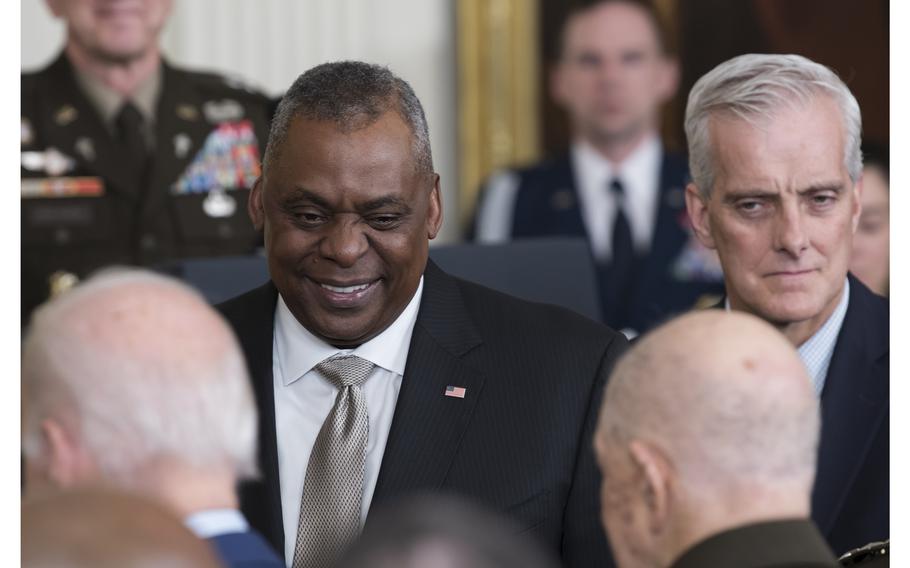

Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin smiles as retired Army Col. Paris Davis walks beside President Joe Biden upon arriving for a White House ceremony in which Biden presented Davis the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions in Vietnam nearly 58 years ago. Looking on at right is Secretary of Veterans Affairs Denis McDonough. (Carlos Bongioanni/Stars and Stripes)

“I was more than happy to participate in the team to see this wrong being righted,” said Deis, who fought in the battle in 1965 with Davis and witnessed his actions on that day. “So, I’m just thrilled that this has happened, finally.”

Davis, who said Thursday that he’s “elated to be an American,” echoed those sentiments just moments after Biden placed the Medal of Honor around his neck at Friday’s ceremony.

“Thank you, President Biden. This medal reflects what teamwork, service and dedication can achieve,” Davis said, wearing the Medal of Honor and a green Army service uniform covered with medals and ribbons. “God bless you, God bless all, God bless America.”

Medal of Honor recipients who attended the White House ceremony on Friday, March 3, 2023, as retired Army Col. Paris Davis received the military’s highest award for his heroic combat actions in Vietnam in 1965 are, from left: former Army Master Sgt. Leroy Petry; Army Sgt. Maj. Matthew O. Williams; former Army Capt. William D. Swenson; Army Master Sgt. Earl D. Plumlee; and former Army Sgt. 1st Class Melvin Morris. ( Carlos Bongioanni/Stars and Stripes)

After Davis left military service as a colonel in 1985, he went on to publish a small newspaper, the Metro Herald, in his home state of Virginia, where he still lives. He also earned two master’s degrees and a doctorate.

One of the first Black soldiers in the Army’s Special Forces, Davis earned his Airborne and Ranger qualifications in 1960 and his Special Forces qualification in 1962. In two tours in Vietnam, he also earned the Silver Star, the Bronze Star with "V" device, a Purple Heart with one Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster and the Air Medal with "V" device. He was inducted into the Ranger Hall of Fame in 2019.

But with all the decorations and accomplishments, Davis is also known for his humility. Biden noted Davis doesn’t like the word “I,” and prefers “team.”

“He felt it was a group effort,” Regan Hopper, Davis’ daughter, said of the battle at Bong Son. “He doesn’t like to be called a hero. He likes the title ‘soldier.’ He wears that with pride.”