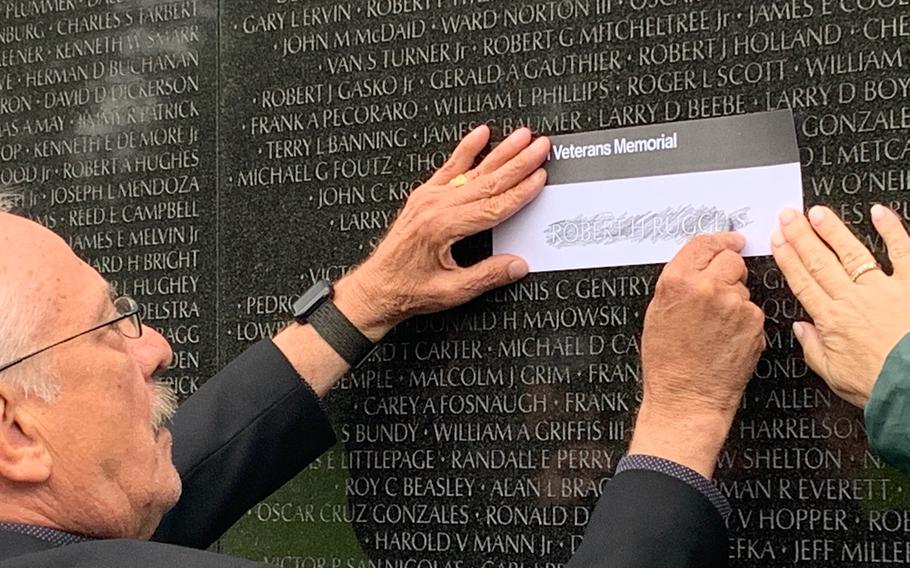

Jan Scruggs, founder of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, makes a rubbing of a name on the memorial’s wall. The Wall of Faces, a project to find a photo for each of the more than 58,000 service members listed on the wall who were killed or missing in action in Vietnam, was completed in August 2022, just in time for the memorial’s 40th anniversary. (Jan Scruggs)

Lorraine Johnson will never forget the day she got the phone call.

It was June 1968. Johnson, then 21, was on a break from her job at Oakwood Hospital in Dearborn, Mich., when she heard her name over the loudspeaker.

“I went to the phone, and my neighbor down the street said, ‘Lorraine, I think you better come home; I think something happened to your brother,’ because there was a jeep in front of my house,” Johnson said.

Her brother, Marine Cpl. Michael Bard, had shipped out to Vietnam in March that year. He stepped on a landmine June 11, dying instantly.

“I had never seen my father cry before,” Johnson said. “… My mom — bless her heart, she’s deceased now — but she’s never been the same after my brother passed. She went to the cemetery every single week.

“… Every time I hear a 21-gun salute or Taps, it just breaks my heart,” she said.

About three or four years ago, Johnson received another phone call about her brother, this time from Janna Hoehn, a florist living in Maui.

Hoehn is one of thousands of volunteers who worked on the Wall of Faces project, an initiative spearheaded by the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund to find at least one photo for each of the 58,281 service members who were killed or went missing during the Vietnam War. The names are listed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and its various replicas across the country, including the traveling Wall That Heals.

After more than two decades of detective work, the Wall of Faces project was completed in August, ahead of the memorial’s 40th anniversary Nov. 13. The names, accompanying photos and biographical information, as well as a place for people to leave remembrances, can be found in a searchable online database at https://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces.

Johnson was able to provide Hoehn with a photo of Bard and share some details about his story. Bard died when he was 19, and being two years apart, the siblings were close growing up.

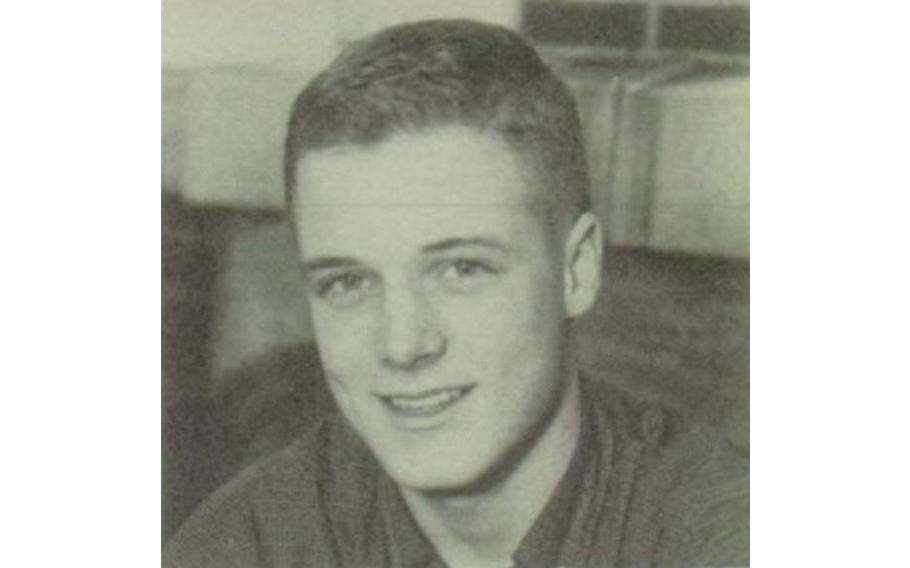

Marine Corps Cpl. Michael Bard was killed June 11, 1968, in Vietnam. He is one of the more than 58,000 service members honored on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. His sister, Lorraine Johnson, provided a photo of Bard to Janna Hoehn, one of the thousands of volunteers who worked to find a photo for each of the names on the wall for the Wall of Faces project, which was completed in August 2022. (vvmf.org)

“He was a stinker, he really was,” Johnson said. “He used to hang around with his friends that reminded me of the mafia. They would drive this old like a Model T, or one of those older cars back in the ’60s. And he used to wear his hair in a DA, you know, the waterfall and the back in a DA and the long sideburns and everything. He was a pistol. He got himself into trouble with the police. … Nothing major, back in the day, you know how kids got in trouble, and that’s how he was.”

He was 18 when he signed up for the Marines, and his parents had to sign for him. His decision to join upset the entire family.

“It broke my heart,” Johnson said.

Getting started

While the work to find the photos really took off in 2009, the seeds of the idea for the Wall of Faces began with the founder of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, Vietnam War veteran Jan Scruggs, following the memorial’s 10th anniversary in 1992.

“I just started getting on the phone with some of these family members, and some of them, they needed some explanation,” he said. “They felt this was kind of taking advantage of the names, faces, fundraising and all this sort of thing. But I was able to start selling the project, and I concluded that 58,000-plus names was a very big hurdle. But it’s the kind of project you can just kind of put on the shelf and from time to time activate it.”

In the early 2000s, Scruggs started pushing the project again, visiting places such as Salt Lake City and Washington state. Despite support from lawmakers in Congress, the Senate and in the states they would visit, the project did not take off the way Scruggs hoped it would.

“The more we did these, the less effective they were — that was the strange thing,” Scruggs said. “You would think that this would really kind of build, but in fact it just didn’t, and I could not get to the bottom of it.”

That was, until Scruggs learned about Hoehn.

In 2008, Hoehn and her husband visited Washington, D.C., and toured the memorials, starting with the Vietnam memorial.

“I did not personally know anyone who died in Vietnam,” Hoehn said. “The young men from my hometown (who died in Vietnam) were about four years older than I was, so I really didn’t know them. I had two cousins who fought in Vietnam, but they both came home. However, something was drawing me to the Vietnam Memorial, and I was really not prepared how it was going to affect me. I mean, I just stood in front of it and cried.”

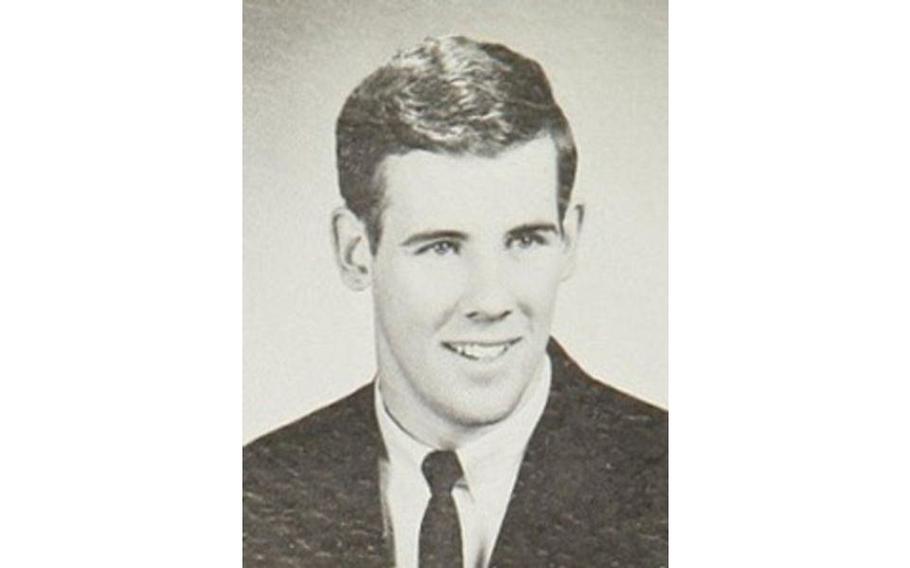

Air Force Maj. Gregory John Crossman went missing in action in Vietnam on April 25, 1968. In 2008, Janna Hoehn took a rubbing of Crossman’s name on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial’s wall. That rubbing led Hoehn to spend more than a decade searching for photos for the service members listed on the memorial as part of the Wall of Faces project. (vvmf.org)

Hoehn took a rubbing of a name on the wall: Gregory John Crossman. While most of the names had a diamond next to them to indicate the service member is known or presumed to be dead, Crossman had a cross next to his name, meaning he was missing in action or otherwise unaccounted for, as another visitor to the wall explained to Hoehn.

Once she was back home on Maui, Hoehn’s curiosity got the best of her. She pulled out the rubbing and started doing research online.

“I just typed his name in and actually quite a bit came up about him,” she said. “He was a pilot, he and his copilot were shot down and neither one of them have ever been recovered.”

Hoehn wanted to find Crossman’s family to give them the rubbing, also thinking they might have a photo of the pilot. But her search turned up empty.

She got in touch with her cousin, her family’s historian, who managed to find a university yearbook photo of Crossman. Hoehn put together a scrapbook page with Crossman’s biography, picture and the rubbing she took at the Wall, but she never managed to find his family.

Three years later, Hoehn learned about the Wall of Faces project from a TV news report. She made a copy of Crossman’s photo and sent it to VVMF. A week later, Scruggs gave her a call.

“He said, ‘I understand you live on Maui.’ … He said, ‘Is there any chance that you might help us find the photos of the Maui fallen?’” Hoehn said.

Six months later, after many visits to local high schools and libraries and an article in The Maui News, Hoehn found the photos for all 42 Maui names on the Wall. But she wasn’t ready to stop. She moved on to her hometown of Hemet, Calif., and then the entire state of California, finding more than 2,000 of the photos, she said. From there, she moved up to the Pacific Northwest, and slowly made her way across the country.

Scruggs recalled meeting with Hoehn in Hawaii to discuss the project.

“She got started, and then the next thing I know she says, ‘I’m gonna get all 58,000 names,’ ” Scruggs said. “Yeah, sure, why don’t you build a space capsule and fly to the moon for a weekend too while you’re at it? And she said, ‘No, I can make this happen by getting volunteers throughout the country.’ … It was kind of like me with the Vietnam memorial, the whole idea of having all the names engraved.”

In all, Hoehn spent about 11 years on the project, scouring websites such as ancestry.com and classmates.com. She worked with newspapers, high schools, historical societies and family members across the country alongside a team of volunteers — she estimates about 12 core team members stuck with it to the very end.

Puerto Rico and New York state proved challenging, she said. But on Aug. 5, Hoehn and her team found their last photo.

“I got very discouraged lots of times,” she said. “The reason that I stuck with it is again, my whole high school years, and I remember how the Vietnam veterans were treated when they came home, and it never left me. It was horrible; they shouldn’t have been treated that way. Whether they were in the service already or that they got drafted, they went and they did what they were asked to do, and then they got treated like criminals when they came home.”

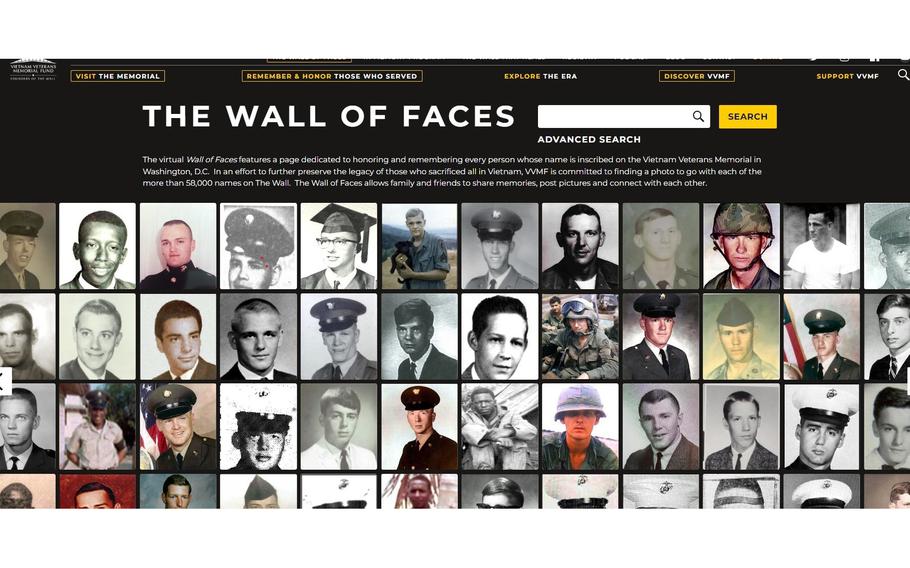

The Wall of Faces on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund website. (Screenshot/vvmf.org)

Putting faces to names

Scruggs retired as president of VVMF in 2015. VVMF’s current president, Jim Knotts — an Air Force veteran of the Persian Gulf War — helped usher the Wall of Faces project to completion alongside VVMF’s Director of Outreach Tim Tetz.

“It’s one thing to see all of the names, and it’s hugely impactful,” Knotts said. “But then when you can see faces for each one and realize that they were just like us — they had hopes and dreams and families and things they wanted to do with their lives, and all of that was given up for their country. So putting a face to a name really has given an additional depth of understanding for the sacrifices people have made.”

Tetz has worked on the project since 2012, when he became director of outreach (he volunteered with VVMF for a decade before). At the time the project was known as Faces Never Forgotten and was renamed the Wall of Faces when Knotts came on board, Tetz said.

“Thousands” of people volunteered to work on the project, Tetz said, although he couldn’t give an exact number. “That’s about like counting the blades of grass in a meadow,” he said.

“Probably a majority of them didn’t have a connection — a majority of the ones who really were the energy behind it didn’t have a connection,” he said. “They might have been Vietnam veterans, and they might have had one connection or something like that, but they really understood and realized after a while that what we could do with this and how we could continue the healing was really something that they wanted to be a part of.”

Once they started working on the project, like Hoehn, many volunteers were sucked in.

Jim Reece, who served in the Army from 1970-’77 and then the Air Force Reserves from 1985-2004, started working on the project with his brother, Tom Reece, in 2005. They started in their hometown of Wilmington, N.C., eventually finding photos for all North Carolina Vietnam veterans on the Wall.

Eventually, the Reeces hooked up with Hoehn. Jim Reece, who lived on Maui for a time, was able to help Hoehn find the last photos from Hawaii.

“We called her the sheriff and the rest of us were referred to as her posse,” Jim said of their group of volunteers. “Our process was, anybody that found a photo, they would send the photo to me and then I would use four different pieces of software to clean the picture up as best I could.”

Reece was never sent to Vietnam, but he considers the Wall of Faces part of his legacy.

“One of these days there’s gonna be a great-grandchild that’s gonna look up on the internet and say, ‘You know, my great-granddad was in Vietnam; I’m gonna look up his name and see if I can find him,’ ” Jim said. “And they’re gonna look, and they’re gonna find [him] just by using Google.”

A promise fulfilled

For Hoehn, the Reeces and others, the stories from family members were what really kept them going.

“I still — I mean, those people send me Christmas cards, and I reciprocate,” said Hoehn, who became the first female and non-veteran president of the Maui County Veterans Council four years ago. “… Some (family members) were very quiet when I would call. One of them said to me one time, ‘I haven’t heard my dad’s name in 40 years.’ It really takes them back; they just stop. I was so afraid at first when I started this project; I thought, what if I’m just gonna upset all of these people? Maybe they’ve tried to put it behind them? They haven’t.”

One story that stuck with Hoehn that she has retold in speeches came not from a family member but from another Vietnam veteran whose best friend was killed in Vietnam.

Army Spc. 4 Douglas Cook was killed Aug. 28, 1969, in Vietnam. While serving in Vietnam together, Cook and his friend and platoon leader, Bowman Olds, made a promise that they would always sing “The Star-Spangled Banner” whenever it was played at an event. (vvmf.org)

In 1969, Army veteran Bowman Olds served as weapons platoon leader and rifle platoon leader with Delta Company, 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry, and Doug Cook was his radio telephone operator. The two became close, bonding over a love of sports — Cook was a baseball fan, and Olds followed basketball.

In between lulls in combat, the two buddies would talk about different things. One topic that came up was “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and how both men were irked when, at special events when the anthem was played, no one would sing along.

“As time went on, especially again when we saw the different casualties that we had in the company there and some of the fatalities that we had, we made a promise to each other,” Old said. “Whenever we are at events where ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ is played, let us not forget that we will sing it. We will sing it. And I said to myself, well, I don’t see that as a problem. And he said the same thing, too.”

Cook was killed in Vietnam on Aug. 28, 1969. To this day, Olds has kept his promise. Years later, at one of his daughter’s high school basketball games, he was singing the anthem when he noticed his daughter looking at him in the stands.

“After the game was over with she came up to me and asked, ‘Dad, why were you singing “The Star-Spangled Banner?’ “ Olds said. “And I almost broke down. And I told her the story. I told her the story about the promise that Doug Cook and I had. And that moment in time, as well as that moment in time that Doug and I made that promise, has always stayed with me.”

Jan Scruggs, founder of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, cleans the memorial’s wall. (Jan Scruggs)