(Tribune News Service) — For the past century, a row of military graves in Tacoma's Oakwood Hill Cemetery has been conspicuously gap toothed. Only a patch of grass has marked the final resting place of David Franklin, Tacoma's only Black naval Civil War veteran.

That changes Saturday when a years-long effort spearheaded by a Civil War historian will finally bring Franklin the white marble tombstone that was forgotten in 1920.

Tumwater-based historian Loran Bures' quest to get Franklin his headstone began in 2017 when he was researching Pierce County's Civil War veterans. He found documents listing Franklin and his burial at Oakwood Hill but when he visited the cemetery he couldn't find his grave.

Using cemetery records, Bures discovered the gap in the neat row of military burials was Franklin's unmarked grave. That's when he set out to learn who Franklin was and right a wrong.

"As any veteran of the United States they should receive their proper burial honors," Bures said. "That's what were trying to rectify after 102 years."

Franklin and the battle for Wilson's Wharf

Little is known about Franklin's early life except that he was born free in New York City in 1840. He enlisted in the Union Navy on Nov. 13, 1863, when he was 23.

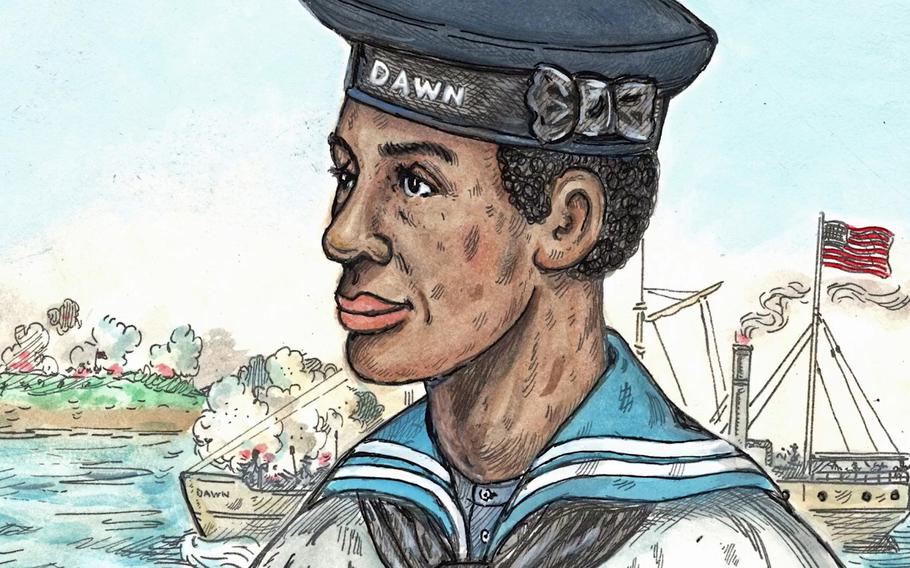

The young seaman was assigned to the Union Navy's USS Dawn, a gunboat, as the officers' steward and cook.

According to Cynthia Wilson, a Seattle-based historian who researches Black Civil War veterans, the 154-foot-long steamer Dawn averaged 65 crew and three officers. Approximately 17 percent of the crew were Black.

The ship was part of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron and, while Franklin served on it, it spent most of its time on the James River in Virginia.

While on the Dawn, Franklin would have taken part in one of the most significant battles in Black Civil War history, according to historians — The Battle of Wilson's Wharf.

On May 24, 1864, about 2,500 Confederate troops attacked the Union supply depot at Wilson's Wharf, Virginia. They were repulsed by two Black regiments totaling 1,100 men, with help from the USS Dawn's guns.

The battle showed that a smaller force of Black soldiers and sailors could defeat a larger, white force.

"It was a loss for the Confederacy with minimal deaths to the African American soldiers (40) but the Confederacy lost 200 men," Franklin said.

"It was a turning point in Black history," Bures said.

Coming to Tacoma

Franklin was discharged on March 31, 1865, Wilson learned from documents provided by the National Archives. A few days later, Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union general Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, Va.

Where Franklin went after the war has been lost to history. But he first appears in Tacoma as a member of a veterans group, the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), in 1888. An 1899 Tacoma city directory lists him as a broiler at the Donnelly Cafe. The cafe was attached to the Hotel Donnelly.

Tacoma was a boom town in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Franklin would have witnessed Washington achieving statehood in 1889 and lived through the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918.

In 1906, records show Franklin enlisted in the hospital corps of the 2nd regiment of the Washington National Guard infantry. He was listed as a cook.

"We know nothing else about it except that," Bures said. "It's amazing that at 65 years old he's enlisting in the National Guard."

According to census records, Franklin died March 16, 1920, at age 79 in his home on South 4th Street.

Franklin's death certificate says he was a widower but Bures hasn't been able to find any records confirming that Franklin had a wife or children. He's still looking for family members. A flag flown over the U.S. Capitol Building on Sept. 2 in honor of Franklin will be presented to a family member if one is found.

Finding Franklin

Bures' discovery of Franklin came when he attempted to locate the graves and final resting spots of every Union Civil War veteran in Pierce County.

"It's important for history and genealogy," Bures said.

He was aided by a 1939 survey conducted by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a Depression-era New Deal agency aimed at employing people for government projects. WPA workers created biographical cards for all war veterans in Pierce County.

The original cards are stored in the Northwest Room at the Tacoma Public Library. About 75% of the 2,000 cards at the library are Civil War vets, Bures said.

During Bures' research, Franklin's card stood out.

"What's interesting about it is what's not there," Bures said. It didn't show how or where he served.

It wasn't until Bures found Franklin's death certificate that he learned the veteran was Black. Further digging in a National Park Service database revealed Franklin had served on the Dawn.

Then earlier this year, Bures went looking for Franklin's grave at Oakwood Hill.

"We went out in the cemetery and found it was unmarked," Bures said.

Righting a wrong

The GAR was the nation's first veteran's organization. It was dissolved after its last member died in the 1950s. Bures belongs to Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, the successor of the GAR.

Bures worked with Oakwood Hills owner Corey Gaffney to confirm that Franklin was buried in the cemetery and was missing his tombstone.

The Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War is considered by the Veterans Administration to be Franklin's legal next of kin and therefore Bures was able to apply for the grave marker. The VA provided the marker, cut from the same Vermont quarry in use a century ago, at no cost.

Gaffney is donating his cemetery's resources to ensure Franklin gets the respect he deserves.

"If you're in the funeral business, you're almost by default a historian," Gaffney said, "This is just me doing my very small part to make sure that Mr. Franklin gets what he's had coming to him."

The redress is personal for Bures. His great-great grandfather, another Civil War veteran, is interred just steps away from Franklin's grave. Both men were members of the Custer Post of the GAR and might have known each other.

Earlier this week, Franklin's tombstone was lying on its back in a cemetery building, waiting for its installation.

In the military section where it will be installed, years of neglect have turned the tombstones a dark gray. Rosettes of orange lichen grow in blotches on the marble.

Gaffney, who bought the cemetery in 2021 with his wife, said he has a VA-approved cleaning solution that will restore the darkened stones to their original white color.

Until then, Franklin's gravestone will be the brightest spot in Oakwood Hill Cemetery.

(c)2022 The News Tribune (Tacoma, Wash.)

Visit at www.TheNewsTribune.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

A years-long effort spearheaded by a Civil War historian will finally bring Civil War Navy veteran David Franklin the white marble tombstone that was forgotten in 1920. (Screenshot from The News Tribune video)