Members of the Buffalo Soldiers arrive at the African American Civil War Memorial in Washington on May 29. (Astrid Riecken/For The Washington Post)

WASHINGTON — The 8-year-old had waited all week to hear the roar of Buffalo Thunder on Sunday morning, and when hundreds of the motorcycles finally arrived in the nation's capital, his eyes opened wide.

Karter Hassell had decided earlier in the day that he would wear black and gold, just like the men and women on the bikes. He didn't know much about them, or the brave soldiers they had come to honor, but he wanted to.

"I'll learn," he said, standing beside his 7-year-old sister, Krista, and his grandmother, Helen Hassell, as they watched the riders pull up to the African American Civil War Memorial in Northwest Washington.

After two years of a pandemic pause, hundreds of Black motorcyclists returned to Washington for the annual Memorial Day tribute to the post-Civil War, all-Black regiments of the Army, known as Buffalo Soldiers, as well as all people of color who gave their lives for American freedom.

The threat of COVID-19 shut down the parade in 2020 and 2021, disrupting the event's nearly two-decade history. But the ride was back Sunday in a big way, and Hugh Valentine, one of the five founding members of the motorcycle club's Maryland chapter, was at the forefront, proudly wearing his Buffalo Soldiers gear.

Hugh Valentine, 91, right, laughs while greeted by members of the Buffalo Soldiers motorcycle club at the African American Civil War Memorial in Washington on May 29. (Astrid Riecken/For The Washington Post)

Valentine, 91, an Army veteran and retired District of Columbia police officer, was thrilled with the return of the ride, which he said is much more about community than motorcycling. After two years of protests for racial justice and a pandemic that has highlighted racial health disparities, Valentine said he hoped the parade would bring attention to the contributions that troops of color have made both at war and in their communities.

Today's racial divisions come well over a century after the Buffalo Soldiers faced discrimination within the military and deadly violence at the hand of civilians. Both then and now, Valentine said, the problems stem from people's exposure to diversity.

"It's up to us to change this," Valentine said. "So that our community values the life of each individual, Black and White."

Chiefly members of the Black 9th and 10th U.S. Cavalry regiments, the Buffalo Soldiers were known for battling Native Americans in the American West in the late 1800s. They protected settlers and built roads and infrastructure, while facing extreme racial prejudice within the Army. Historians say American Indians gave the nickname to the troops because of their curly hair - and as a sign of respect.

"These people served the country, and as Black men, they had so many struggles," said Bobbie Coles, of Silver Spring, Md. "They were the last ones that got benefits and recognition."

At Sunday's ride, organizers emphasized the Buffalo Soldiers' spirit of service.

"We ride motorcycles a lot," said Jeff "Shorty Airborne" Freeland, the Maryland charter's president. "But community service is what we do."

The U.S. flag is seen at the African American Civil War Memorial in Washington, D.C., on May 29. The Buffalo Soldiers, who are African American motorcyclists from across the country, came to the memorial to honor the people of color who paid the ultimate price for freedom in this country. (Astrid Riecken/For The Washington Post)

The Buffalo Thunder event is the group's biggest fundraiser, and its cancellation the past two years meant the Maryland branch had to scale back its charitable work in the region. They could longer able offer as many low-income families scholarships, Thanksgiving meals and Christmas gifts. This year, the group hopes to give more than $40,000 in college scholarships to local students and help as many as 150 families with holiday turkeys.

Mason Monroe, chairman of the Buffalo Soldiers of Maryland Foundation, said they didn't expect as many participants this year because of COVID-19, which meant the event was likely to yield less than half the $20,000 it did during a normal pre-pandemic ride. The foundation relies on individual and corporate donations year-round, and members participate in other functions to raise funds to help majority Black communities in D.C. and Maryland's Prince George's County.

That community engagement was the mission of the club from its creation nearly three decades ago, Valentine said. It was, he said, meant to recreate the spirit of service of the Buffalo Soldiers — 19 of whom were awarded Medals of Honor.

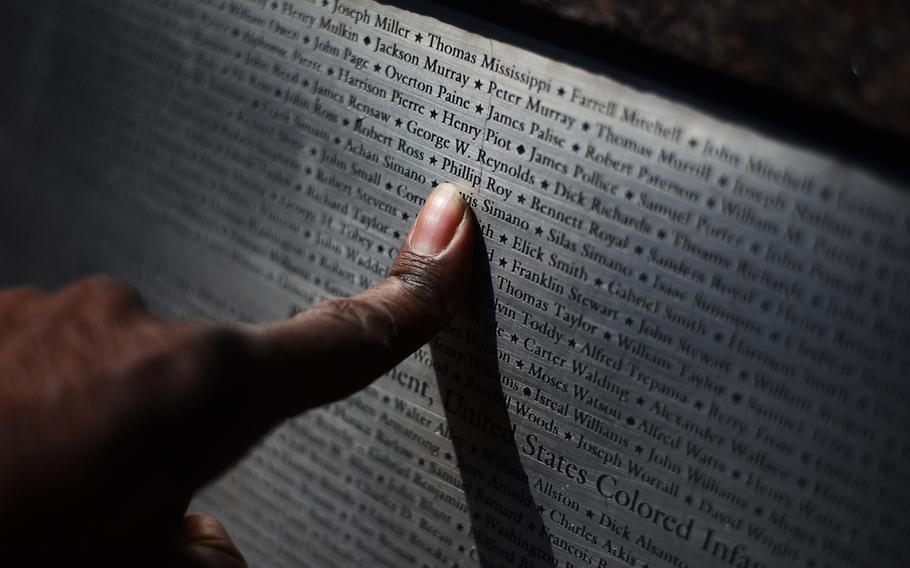

Photographer Roy Lewis points to the name of his great-great grandfather, Phillip Roy, who served in the infantry during the Civil War and whose name is engraved at the African American Civil War Memorial. (Astrid Riecken/For The Washington Post)

On Sunday, about 400 Buffalo Thunder riders from across the country, many from as far away as Florida and Idaho, rode from a Landover, Md., church parking lot to the African American Civil War Memorial at U Street, passing waving crowds along the 14-mile route.

"It's really nice to come back together and be able to fellowship in safer times and pay homage to the Buffalo Soldiers and their sacrifice for the nation," said Kisha Brown, a Maryland chapter member and event organizer.

Hassell said the event was a history lesson for her grandkids. Dressed in Civil War attire, reenacting a schoolteacher of the era, she walked with Karter and Krista around the statue of Black uniformed armed servicemen as they read some of the more than 200,000 names engraved at the African American Civil War Memorial.

"It's a teachable moment," Hassell said, "as well as a day of celebration."