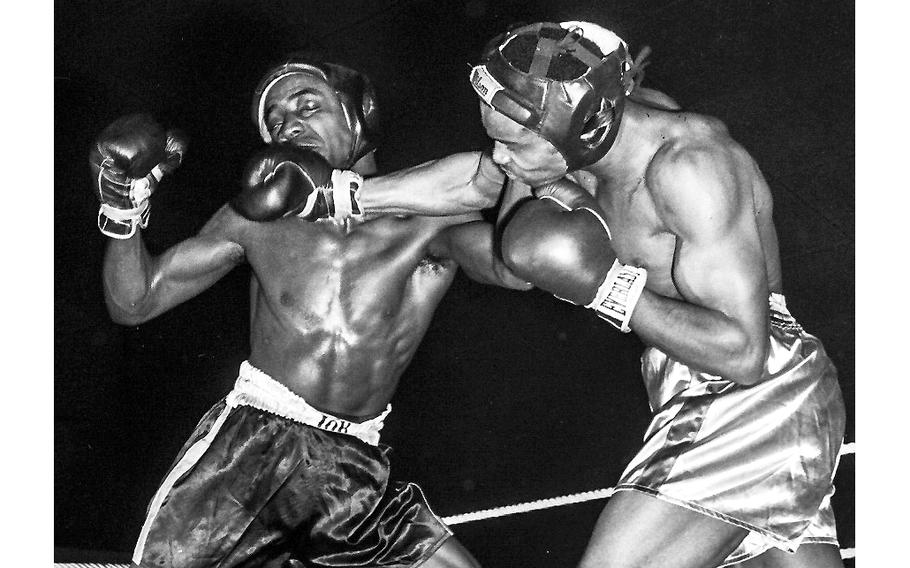

Hanau, West Germany, March, 1957: A fighter connects with a right during the opening round of the U.S. Army Europe northern regional boxing championships at the Pioneer Kaserne gym. (Red Grandy/Stars and Stripes)

BUFFALO, NY (Tribune News Service) —Patrick Welch stepped on a land mine in 1965 during a firefight in Vietnam and spent his late teens in two military hospitals recovering from his injuries.

He since has also faced the slow, steady ravages of Agent Orange.

The U.S. Armed Forces showered the herbicide over much of South Vietnam in a tactical strategy to clear leaves and vegetation for military operations for a decade, starting in 1964.

“There are places today in Vietnam where nothing grows because of the spraying,” said Welch, who along with veterans from the war continue to fight for better health care for those who struggle with its long-term effects.

The federal Department of Veterans Affairs since the 1990s has acknowledged a growing number of conditions tied to the spraying, including several forms of cancer and neurological diseases.

Last year, it added Parkinson’s disease, which Welch and other advocates estimate impacts as many as 110,000 soldiers who served in Vietnam.

He was diagnosed in 2020 and has since become involved in his latest battle, this time to get the VA to cover a therapy he calls “an extraordinary gift” in the fight to address his symptoms.

Parkinson’s boxing.

Welch is among a half-dozen veterans taking part in a pilot program in the VA Western New York Healthcare System to learn whether the therapy works well enough to expand across the VA system — and cover the cost. The disease

Parkinson’s, a neurodegenerative disorder, slows dopamine production in the brain, disrupting movement and sometimes speech. It can cause tremors, mostly in the hands and arms, and stiffen limbs, mostly the legs.

The fear of stumbling and falling intensifies with growing symptoms, as does a sense of discouragement that can easily become isolating.

“Because you don’t want to move, you can become very complacent, very sedentary,” said Welch, 74, a Marine Corps veteran who lives in Amherst. “When I was diagnosed, I fell back into a bit of depression because here’s another thing I have to deal with, after all the stuff I’ve dealt with for 60 years. And if you’ve talked to other veterans, we can leave the war in Vietnam, but Vietnam never leaves us.”

Like most with Parkinson’s, Welch takes two medications, rasagiline and carbidopa, which can address depression while easing stiffness and shakiness. They also can come with side effects that include headaches, joint pain and gastrointestinal discomfort.

The gym

Dean Eoannou, a 67-year-old former Ford plant shift manager and longtime boxing trainer, opened his first Parkinson’s Boxing Gym seven years ago in Kenmore. He opened his second in the region earlier this month at 4501 Southwestern Blvd., in Hamburg.

Welch and several veterans enrolled in the VA pilot program were among those on hand for the grand opening. Letters framed and hung on the walls of the new, 1,800-square-foot facility hail the gym’s track record. They come from doctors affiliated with the Mayo Clinic, UBMD Neurology and Dent Neurologic Clinic.

Boxing coaches include Taylor Atkinson, a former Golden Gloves champ who served six years in the U.S. Army Fourth Infantry

Division, including 2011-12 in Afghanistan. He sustained a traumatic brain injury during his service and struggles off and on with post-traumatic stress.

“Working with the veterans is just as helpful for me as it is on them,” said Atkinson, 35, of Marilla.

Twice a week he helps train John Beatty, 67, of Lancaster, a retired ironworker who served in the Navy from 1973 to 1977, and was a bouncer and heavyweight boxer before, during and after that service.

“Parkinsonism is a progressive disease,” Atkinson said, “so if you’re not getting worse, you’re still winning. You get in here and you start to make small progress, and you feel like you can build on it. I’m confident that there’s nothing we can’t fix.”

The training

The noncontact therapy is designed to help those with movement disorders including Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis.

“It’s a whole team effort,” said Eoannou, who became certified to teach Parkinson’s Boxing after watching a “60 Minutes” episode several years ago. Similar gyms have cropped up across the country, though he has added flourishes developed through decades as a boxing trainer.

Welch started the therapy last October, going through exercises on grids taped in patterns both inside and outside the ring.

The lines, boxes and dashes on the gym floor promote walking by landing the right and left feet at distances of varying length. Students are encouraged to focus on breathing while counting off steps aloud in alternating numbers and letters as they move forward. Combinations might include 1-A-B-C, 2-E, 3-F, 4-G, 5-H and so on.

Jennifer Taggart, a certified personal trainer who worked for more than a decade at World Gym and LA Fitness, often puts Welch through his paces.

While hitting a speed bag that dangles under a circular slab of wood, Welch and other clients wait for the bag to strike the board three times before striking it again, a repetitive 1-2-3 cadence that changes with how hard and quickly the bag gets struck. The body must be in alignment, the brain engaged, to strike the bag directly at the proper time, and build momentum.

“I hardly hit it the first time,” Welch said. “It hit me. That’s when she said, ‘move back a scooch.’ “

The strategy

Fitness alone tends to build muscle memory. Parkinson’s boxing was designed not only to boost strength but forge neuroplasticity, a process that builds new electrical connections between the brain and the body.

“Movement is always good,” Eoannou said. “Plasticity is the key. When a network with Parkinson’s shut down, it shuts down because there’s no dopamine. “Here, you build a new network on different real estate in the brain.”

The mind-body connection also builds spirit.

“If you walk into this building, and you’re feeling down,” Beatty said, “when you walk out, you don’t feel that way anymore.”

New students are evaluated before training starts. Goals are set, measured and re-evaluated each month.

Eoannou and his trainers tracked 98 of his clients over six months in his Kenmore gym for part of a study led by researchers at Northwestern University. They reduced falls by 87%.

“The same 98 people, when we shut down over Covid for two and a half months, falls went up 53% and medication went up 22%,” the gym owner said.

Eoannou can tick off clients with several kinds of neurological conditions the training helped.

“I’ve never seen anyone come here with a balance issue that we haven’t improved,” he said. “We routinely get them out of walkers and out of wheelchairs. Patrick is a perfect example. He came in with a walker and had a brace on each knee. Now, he’s walking.”

VA involvement

Hourlong training sessions cost $125. Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield of Western New York and Independent Health offer its members with Parkinson’s the program with $10 copays per class.

Those with Parkinson’s enrolled in VA health care are eligible for free training sessions for up to a year. Learn more by calling Pam Kaznowski, a recreational therapy supervisor with the VA Western New York Health System, at 716-289-6764.

The pilot program will help the VA decide whether to cover the cost of the therapy as it does others, including sled hockey, PGA golf, outrigger canoeing, horse-riding and art therapy.

These programs are especially important for veterans with post-traumatic stress and other health conditions that raise the risk of suicide, Kaznowski said.

“Sometimes you do have to start with medication to help somebody, but then you go to exercise and programming,” she told The Buffalo News April 8, during the grand opening of the Hamburg gym. “I don’t want to say just veterans, but other program participants are reducing their medications. One of the men here just came up and said, ‘I’m down three different pills because of this program.’ “

She is tracking the health progress of those who enroll in boxing training to share with the VA.

“I don’t want to say this is a miracle,” she said, “but it’s pretty close.”

Addressing costs

Vets Herd, a Lancaster nonprofit that empowers disabled veterans in the region, has raised $30,000 to cover the cost of the pilot program, largely through Foundation 214, started two decades ago by Western New York business owner Sal Alfiero, a combat pilot during the 1970s with Marine Attack Squadron 214, better known as the “Black Sheep.”

The effort also has friends tied to Congress.

Rep. Brian Higgins, D-Buffalo, has been working since 2019 with former Republican congressman Jack Quinn and Quinn’s brother Jeff, who both have Parkinson’s and have benefited from the Parkinson’s Gym.

In February, Higgins introduced the bipartisan Boxing Therapy for Parkinson’s Access Act that would require the VA to cover boxing classes for veterans diagnosed with Parkinson’s or similar movement disorders. The Michael J. Fox Foundation supports the bill.

“When people develop Parkinson’s, a lot of them cut their medications because the side effects sometimes lead to falls,” Higgins said. “This physical activity not only helps them add fluidity but is a substitute in many cases for some of their medication.”

Greater need

Roman Figler, of Grand Island, diagnosed in 2016 with Parkinson’s, hid his condition from co-workers at the Army Corps of Engineers for three years before he started boxing therapy.

“It’s given me a real confidence,” he said. He son led a fundraiser that raised $32,000 toward renovating the space for the new Hamburg gym.

Figler and others hope the VA pilot program will help make training more affordable for people like him. So does Higgins.

“The Parkinson’s Access Act will have the VA cover for veterans the cost of Parkinson’s boxing,” Higgins said. “Some (private)

insurance companies will cover it, some won’t, but the more you get to do so, the more universal coverage will become.” Welch relishes his latest fight.

It follows a string of challenges that include joining the service at age 17 after getting kicked out of high school. Recovering from serious war injuries and graduating with an accounting degree from the University at Buffalo. And changing jobs after two decades to help launch a computer software company with clients in 50 countries.

It also includes veteran advocacy leadership roles in regional, state and national Vietnam veterans organizations, and as director of Erie County Veterans Services a decade ago.

“I’m very pleased right now with the group we brought together,” he said. “We’ve got a good collaboration of people from most aspects of the community working on this project.”

(c)2022 The Buffalo News (Buffalo, N.Y.)

Visit The Buffalo News (Buffalo, N.Y.) at www.buffalonews.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.