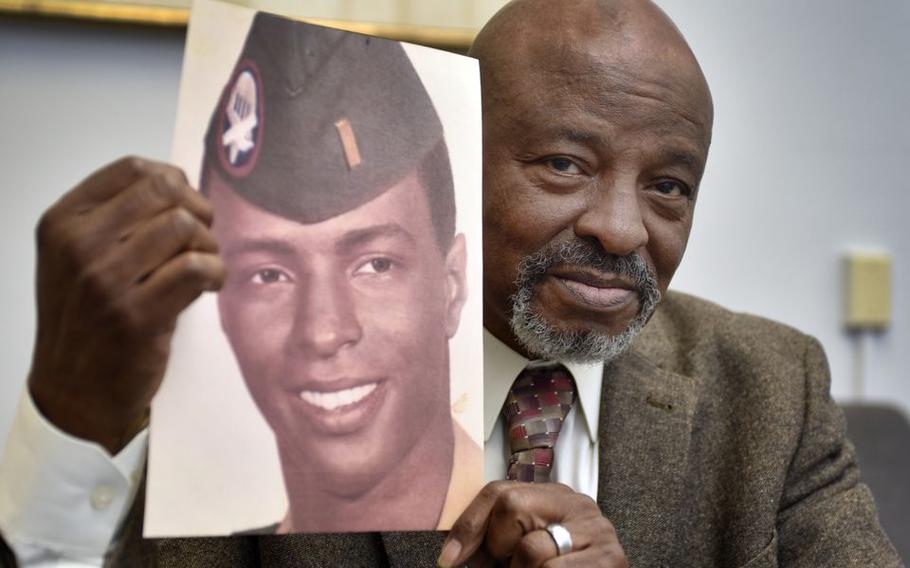

Local National Association for Black Veterans commander Tony Francis with a photograph from when he was 21 years old. (Don Treeger, The Republican/TNS)

(Tribune News Service) — Bernard McClusky said when he went off to serve his country in Vietnam, he was a happy-go-lucky guy.

""My goal was to be an entertainer. Actually, it still is," said McClusky, whose war experiences in 1967 and 1968 led him on a path to help modern veterans that continues today.

"By the time I came back, things I used to think were funny no longer seemed funny. The only comfortable times were when I was around other Vietnam veterans. I didn't know why I had changed," he said.

McClusky is now 75, an average age for the Vietnam Era veteran who now serves as the predominant face and voice for United States military veterans. The youngest surviving World War II veterans will be 95 this year. For those who served in Korea, youth means 90.

"The country has come to grips with the bad treatment given to Vietnam veterans. And today, it's the Vietnam veterans carrying the flag for the others," said Springfield, Mass., attorney Frederick A. Hurst, whose brother, Ronald C. Hurst, was 21 when he was killed in Vietnam on April 12, 1967.

Other than those who served as teenagers in the early 1970s, today's Vietnam Era veterans are at least in their 70s. Many are in their 80s. And they are leaving us: according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs in 2021, approximately 530 Vietnam veterans die every day.

That's why Anthony Francis doesn't keep in touch with many of them.

"What veterans miss (after leaving the service) is the closeness. You've been waking up with these guys and then none of them are around," said Francis, 74, the commander of the Springfield chapter of the National Association for Black Veterans (NABVETS).

The Springfield chapter has about 45 members, according to McClusky, its secretary and also director of the Vietnam Veterans of Massachusetts.

"You don't want to write a letter and hear, 'Billy died in Vietnam,'" Francis said. "In my mind's eye, they all came home. I spent time in the National Guard after that, and I do stay in touch with some of them."

He'll never forget them, though. "I lost all my pictures with guys I'd served with," Francis said. "That still upsets me."

For African American veterans in greater Springfield and beyond, their loyalty and devotion to their fellow veterans, and to their country, remains as strong as ever.

As has often been documented, the return of the Vietnam veterans was treated not with parades, but with abuse, disrespect and neglect. It is an infamous chapter in our history that affected veterans of all colors, but it also came during a time of civil unrest that forced African Americans to face other layers of challenge, which left countless among them confused and emotionally damaged.

"When I came back, I felt out of step. Everybody else was on their right foot and I was on my left foot," Francis said.

The men of NABVETS and other Vietnam Era veterans remain steadfastly proud to have served their country — proud enough, in fact, to not only appreciate its potential, but address its flaws and improve it today.

They are determined to ensure that veterans of all of America's subsequent conflicts not only receive the appreciation denied Vietnam veterans for decades, but are made aware of benefits and opportunities that might otherwise go untapped.

"I didn't know about Veterans Administration benefits until the late 1980s. People who didn't look like me knew about them. There's a need for our organization," Francis said.

Many of them believe that should be required of all Americans in some way — not just men like McClusky, who received his draft notice on Nov. 8, 1966, and the many others who enlisted.

"We were called to serve our country. And it trained us to make our country better — for all of us," McClusky said.

That explains why NABVETS is focused primarily on African American veterans but excludes no one. The "B" in its acronym notwithstanding, the organization also seeks to help Hispanic, Asian and other groups — including whites — who have served in the military and could use a helping hand and support.

In many respects, they have succeeded. As a rule, Americans opposed to military engagements no longer blame the soldiers, as many did with Vietnam — so much so that returning service personnel were told not to wear their uniforms if they left their military base.

McClusky said Vietnam veterans have also worked tirelessly and successfully to remove lingering skepticism of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and treat as a genuine and serious medical condition. He says that helps not only returning veterans but police and fire personnel, victims of rape or violence and others affected by traumatic experiences.

When Black veterans discuss their memories today, their pride in having served their country is inspiring.

"Even as African Americans and descendants of slaves, we have a lot of unbelievable rights compared to many other nations," says Milton Jones, past commander of the Springfield NABVETS chapter. "We have the opportunity to make change here. If I had to make a choice of where to live, I'd choose here."

Francis says he enlisted "when I was young and dumb," but his tone says he does not regret his decision.

"My great uncle served in World War I. I had uncles in World War II. This was my generation's war," said Francis, who rose to Army second lieutenant in Vietnam from 1969 to 1970.

"Seems like just yesterday. Wars like that, you're fighting for the guys you're with. Even if you didn't know them, it's for them," Francis said.

Jones, 76, acknowleges his military experience differed from that of others. After enlisting in the Air Force in 1967, he served four years (as opposed to two for draftees), but not in Vietnam.

Instead, he was deployed at American bases in Europe, but says had orders come to send him to the war, he was ready to go.

"I am sometimes embarrassed to say how well I was treated. There were problems, as there always will be, but mine were probably on the low end."

Not everyone was so fortunate.

"I faced racism in the military, and I wasn't prepared for it," Francis said.

Francis was the only Black graduate in his Officer Candidate School. He'd grown up in the North but had some experience in the South, where unwritten rules about addressing white people — and never looking them in the eye — were still the norm.

Those prejudices did not vanish when he put on the uniform and risked his life to serve his country.

"I was with the 82nd Airborne at Fort Bragg, (N.C.), and my company commander was from Georgia. I was set up purposely to fail," Francis said.

He didn't. His experience as a combat engineer in wartime will always be with him, though.

"Even today, I still walk the perimeter, making sure the doors at my house are locked and the windows shut," Francis said.

“I saw more racism in the officer ranks,” he recalled. “It contributed to my PTSD, because there was no one I had confidence I could talk to. My first commander in Vietnam was from Alabama, and another was from South Carolina.”

When Francis asked one of them a basic question, he was told not to question his officer or he'd be thrown in jail.

Hurst does not dispute that bigotry existed in the military, but he thinks the service branches have advanced integration in ways beyond some other areas of American life, and certainly in modern times.

"Don't get me wrong, there was discrimination at Normandy in World War II, too," said Hurst, 77, who did not go to Vietnam, but said he would have served if called.

"In World War II, all my uncles fought in the Africa campaign or the Pacific campaign," said Hurst, who was deferred because one brother was killed, another was permanently disabled and a third was serving in Korea's Demilitarized Zone.

Hurst nonetheless paid an unimaginable price.

"I remember how I'd been shy but Ron sang and danced and was a ladies' man, until he got married and settled down. My brother's tour had a month left, and he had been communicating with me about bringing his family to D.C.," said Hurst, who was attending Howard University and thought his brother would, too.

"I got a call from his wife that he'd been killed. Ron was a year younger than I. My older brother, James, he suffered and suffered and never recovered from the Vietnam War," Hurst said.

"It's a doggone shame. None of this was their fault. In some ways, I think (Ron) came out of it better," he said.

Francis' memories extend far beyond the hostility of bigots.

"I loved my guys — Black, Hispanic, Native American, Asian and Caucasian. We had one Caucasian radio man from a wealthy Kentucky family who could have avoided service, but he felt he should serve his country.

"Not long before his tour was up, he volunteered to go out (on a risky patrol.) I said no because he was almost home," Francis said. "He talked me into it but then we hit a monsoon, so he was out there longer. I'm thankful he came back."

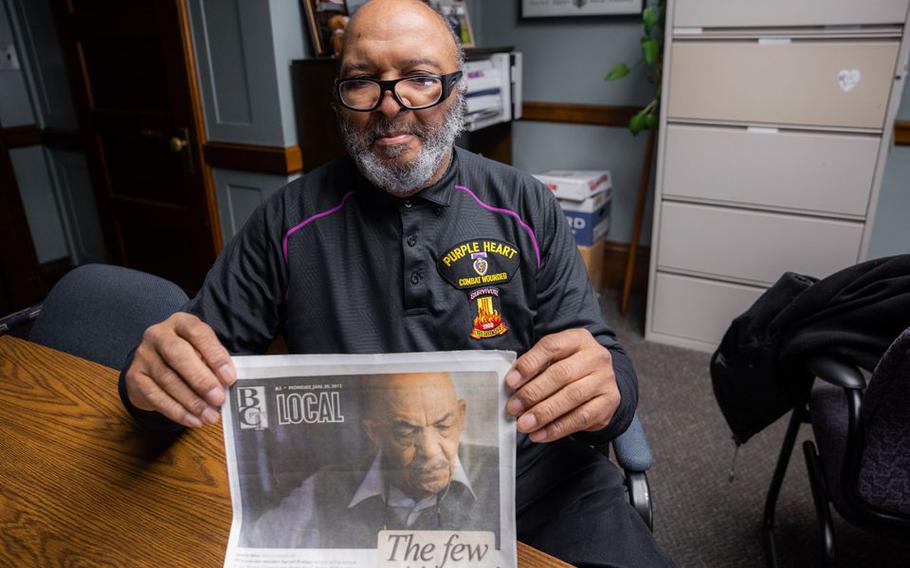

"They didn't want (Black military personnel) in the first place," says 74-year-old Thomas M. Belton, who was wounded in Vietnam and earned a Purple Heart for his service in 1968 and 1969.

Thomas M. Belton shows an article featuring his cousin Harold Phillips, who was one of the first African Americans to serve in the U.S. Marine Corps who received the Congressional Gold Medal. Belton has been Springfield’s Director of Veterans Services since 2011. (Leon Nguyen, The Republican/TNS)

Belton encountered prejudice in the military, yet never regretted serving, even though his job at Pratt & Whitney had provided an opportunity for a deferment.

“The Marines Corps trained me well,” said Belton, the Springfield director of Veterans’ Services since 2011. But it wasn’t easy, he said.

"I was in an aviation unit, where not many people of color were. That was one of the problems. I was made aware of who I was every day," Belton said.

Whatever difficulties Belton endured in the military were compounded by the mood he encountered coming home.

"The way I was greeted in Boston, it didn't matter what color you were. If you were a veteran, they didn't think you were anybody," he said.

According to McClusky, "we were considered knife-chewing, mad, crazed baby-killers. The only one glad to see me when I came back was my mommy. And African Americans did not feel particularly free at home.

"I was in Vietnam when Martin Luther King was killed in 1968. I was torn about whether to get involved in that story or stay in the military."

McClusky wound up doing both by using his military background to facilitate assistance and change. He credits his wife, Alvine, and son, Adrian, for helping him readjust.

"We've been married 51 years. And I'm still chasing her," said McClusky, smiling.

He says Vietnam vets can feel some kinship with Korean War veterans, whose numbers are dramatically dwindling — and whose war, in some history interpretations, is being forgotten.

"We were the bastard children," McClusky said of veterans from both conflicts.

Francis ran into the same disrespect when he came home.

"I went back to school in Brooklyn, and you didn't (tell) anyone you served. But if I was asked, I didn't lie," he said. "One girl asked me, 'How many women and children did you kill?'

"I didn't say a word. But a guy told me we were all suckers to go, and I looked at his throat. I didn't do it, but he didn't realize how close he came to dying that day."

Given sectional prejudices and the mood of the 1960s, tension in the military was probably inevitable.

"When you have someone from Alabama sleeping in the same barracks as someone from New Jersey, sometimes sparks fly," Jones said. "But from a military perspective, you put that aside. The foxhole mentality is that you don't care about the color of the man next to you, or where he came from — you care if he can shoot a rifle."

"When you need help, you don't look at color or creed. You look for help," McClusky said.

The Vietnam Veterans of America was founded in 1978 with the motto, "Never again will one generation of veterans abandon another." For Black veterans, the challenge of coming home to an uncertain future, a divided country and hostility from anti-war activists, veterans of previous and popular conflicts, and African Americans who felt they'd been used and manipulated, that return was even more difficult.

McClusky and Jones are among many who believe every American should serve the country.

"I wouldn't trade my military experience for anything. It built me to train and taught me to work together with people. Freedom isn't free — I think everybody should go in," said McClusky, who said he'd support the return of a draft.

"The North Vietnamese were dropping leaflets, saying 'it's not your war. We don't want to kill you.' But we knew we were serving our country, and that was the larger cause," Jones said.

"If we could choose our war, I wouldn't necessarily have chosen Vietnam. But you don't get that luxury."

In Vietnam, Belton realized the value of education when he encountered a serviceman who kept bringing the wrong ammunition because he couldn't read the orders.

Upon his return, Belton used VA support to attend Springfield Technical Community College.

"Education determines who goes to war and who doesn't, who's on the front lines and who's in the rear, carrying the gear," he said.

Local African American veterans first organized under the auspices of the Winchester Square Vietnam Era Veterans of Greater Springfield. McClusky recalls the men hoping they had enough gas to reach their meetings with state legislators.

Today, well past the normal accepted retirement age, African American Vietnam veterans still soldier on. Their experience, and their patriotism, is devoted to helping others in a nation that still needs them.

"We want to make sure veterans and people of color aren't forgotten," Francis said. "People waste so much time (with racism). It's still out there, a sickness we're not addressing.

"But we're for everybody, not just in the military but in the community. We want to effect change there, too."

(c)2022 The Republican, Springfield, Mass.

Visit The Republican, Springfield, Mass. at www.masslive.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.