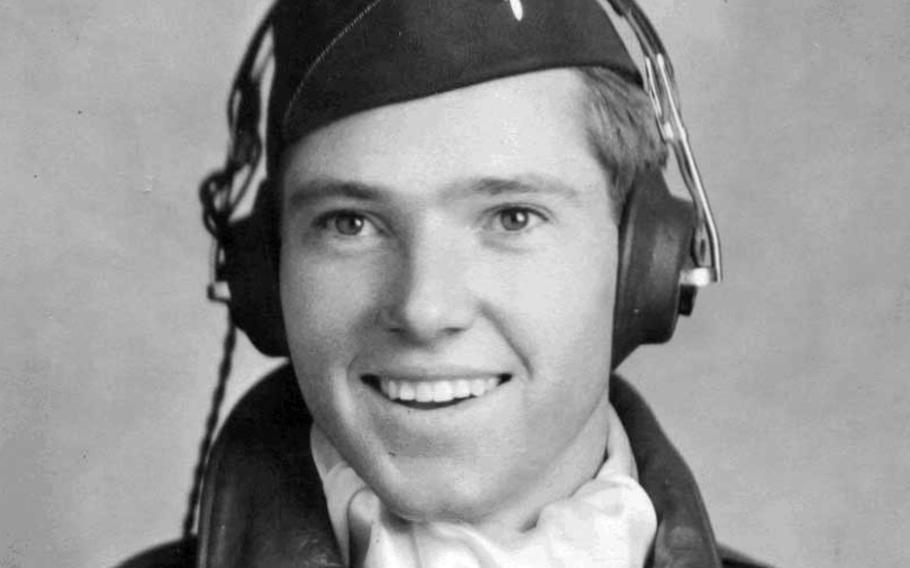

As a pilot with the Army Air Forces, John Billings flew 39 missions for the Office of Strategic Services, a wartime precursor to the CIA. (U.S. Army)

With Nazi troops on the defensive and World War II nearing an end, Army Air Forces pilot John Billings was enlisted for a risky operation organized by the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime precursor to the CIA. The top-secret mission would require him to fly deep behind German lines at night, avoiding enemy planes and antiaircraft guns, and drop three Allied spies over a frozen lake in the Austrian Alps, 10,000 feet above sea level.

Once there, the agents could infiltrate nearby towns and acquire crucial intelligence on the movement of Nazi troops and supplies through the Brenner Pass, along the border between Italy and Austria. Two of the spies were Jewish, increasing the risks they faced if the mission ended in capture. By some accounts, the flight itself was so dangerous that Britain’s Royal Air Force refused to go.

“Naturally, I signed up for the job,” Billings wrote in a 2021 autobiography, “Special Duties Pilot.” “If they’re crazy enough to jump there,” he recalled saying, “I’ll be crazy enough to take them.”

The mission, known as Operation Greenup, was considered one of the most successful OSS operations of the war; its operatives are sometimes described as “the real ‘inglourious basterds,’” after director Quentin Tarantino’s movie of the same name. Greenup was one of 39 OSS missions flown by Billings, who later worked as a commercial pilot and volunteered with the organization Mercy Medical Angels, flying patients who couldn’t afford to travel long distances for health care.

“John Billings is the prototype of an American aviator,” retired Air Force Gen. Norton A. Schwartz said last year, just before the publication of Billings’s autobiography. He was 98 when he died March 4 at his home in Woodstock, Va., four weeks after flying his single-engine Cessna Cutlass for the last time with help from a co-pilot. The cause was congestive heart failure and renal failure, said his wife, Barbara Billings.

“Everyone has some sort of addiction, and flying’s mine,” Billings told the Santa Cruz Sentinel in 2015 at age 91, in the midst of a 13-day flight around the contiguous United States with his longtime co-pilot, Nevin Showman. “But I have an excuse. I was born with a genetic defect. My feet hurt if I stand on the ground too long.”

Billings deployed to Italy in August 1944, tasked with flying the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, a heavy bomber that he jokingly referred to as “the pregnant pig.” He completed 14 combat missions before being assigned to the 885th Heavy Special Bombardment Squadron, which he later discovered was a front for the OSS. “We weren’t even supposed to mention that we were with OSS. The less people that know, the safer it is for all of us,” he told CNN in 2016. “I was a good boy. I didn’t talk about it to anybody.”

Stationed in the southern city of Brindisi, about 70 miles from the spy agency’s headquarters in Bari, Billings flew a camouflaged B-24, painted gloss black to avoid being seen at night. He and his fellow aviators dropped supplies for partisans and undercover operatives, including 500-pound containers full of gold coins used to bribe Germans. They also dropped spies, notably in Operation Greenup.

Launched in February 1945, the mission was aborted twice because of bad weather. Billings recalled that the third attempt went forward after he was told that the wind speed atop the Alps would exceed 200 miles per hour that night - an ominous warning that bore out when the plane encountered a powerful downdraft that caused it to drop 6,000 feet in 18 seconds, according to the flight navigator.

In his autobiography, Mr. Billings wrote that he used emergency power to give the plane’s four engines more horsepower than they were designed to withstand, helping to slow the descent and stop the fall. The three spies soon parachuted successfully to the ground, landing in waist-high snow, and sledded downhill, heading toward Innsbruck.

The operatives included Frederick Mayer, a German-born Jew who posed as a Nazi service member separated from the rest of his unit; Hans Wynberg, a Dutch-born Jew whose parents and younger brother perished in the Holocaust; and Franz Weber, an Austrian officer who had defected from the German army.

Mayer “gathered vital intelligence that hastened the war’s end,” Charles Pinck, president of the OSS Society, a group that honors the wartime agency, said in an email. Even after he was captured and tortured by the Germans, Mayer persuaded the regional Nazi authority to surrender Innsbruck to approaching Allied forces, “saving untold thousands of lives,” Pinck added. “He was the only member of the OSS who was nominated for the Medal of Honor.”

Billings became good friends with Mayer, who died in 2016, two years before lawmakers awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to the OSS as a whole after a years-long campaign for recognition for the spy agency. “I’m happy that the OSS got recognized,” Billings told The Washington Post after an award ceremony he attended with about 20 other OSS veterans. But, he added, “So many people, deserving people, are not here anymore. It would have been nice to have them know about it as well.”

The oldest of three children, John Malcolm Billings was born in Winchester, Mass., on Aug. 7, 1923, and grew up in Scituate, a coastal town south of Boston. His mother was a homemaker, and his father was a millwright who took Billings for his first flight as a third birthday present.

The ride was “probably 10 to 15 minutes, but it seemed like the whole afternoon,” Billings told the Virginian-Pilot in 2018. “That really buried itself under my skin, and it’s still there.” He took his first flying lesson at 15 and entered aviation training after enlisting in the Army in 1942.

Billings retired from active duty as a captain in 1946, having received honors including the Distinguished Flying Cross.

His first wife, Nancy Gardiner Billings, died in 1995. In addition to his wife of 24 years, the former Barbara Staley, survivors include three children from his first marriage, Susan Billings of Dumfries, Va., Leslie Billings of Alexandria, Va., and Lee Billings of Stafford, Va.; two stepdaughters, Lisa Oleskie and Lori Staley, both of Woodstock; a brother; six grandchildren; and 13 great-grandchildren.

Billings spent nearly all of his commercial aviation career at Eastern Airlines, where he worked as a pilot before going into mandatory retirement at age 60 in 1983. He continued flying for nearly four more decades, upgrading his Cessna to fly 462 “Angel Flights” as a volunteer pilot with Mercy Medical Angels.

As Billings told it, his passengers - including sick or disabled children - paid for the trips in “big smiles and big hugs,” with aviation costs covered by him and his co-pilot, Showman, who developed lasting relationships with some of the patients.

“One time, an adorable little girl asked me, ‘If I’m going on an Angel Flight, does that mean I’m an angel?’ Naturally, I confirmed it,” Billings told the Patriot Ledger of Quincy, Mass., in November, when he retired from the volunteer flight program because of a recent heart attack. “By the end of the flight,” he continued, “both of us were absolutely convinced.”