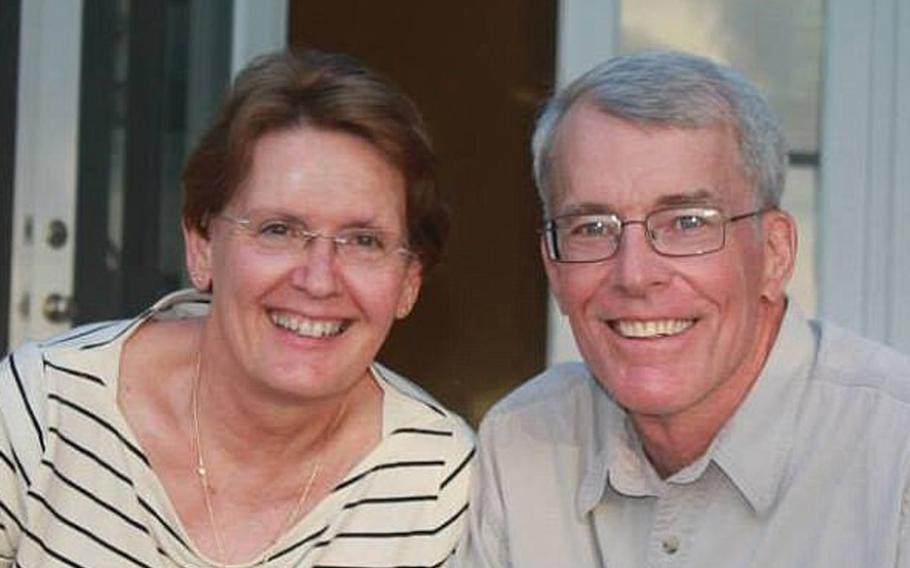

Pamela and Stephen Kruspe, who were married 42 years, appear in this undated family photo from Facebook. Stephen Kruspe, 65, is charged with first-degree murder in the fatal 2017 shooting of his wife and now seeks to be released from Palm Beach County Jail before his trial. (Facebook/South Florida Sun Sentinel/TNS)

(Tribune News Service) — After raising three kids while her Marine husband was shipped around the world, Pam Kruspe was ready to enjoy retirement in Lake Worth. But at age 59, she was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s. Her husband, Steve, tried to care for her. After a year, he put her in an assisted living facility. When Pam was lucid, Steve said, she begged him to kill her. So he did.

Her younger brother was already at the courthouse, waiting by the wide window.

She walked past him without a word.

Stephanie Wilhelm and Matt Kruspe used to be close, used to talk every week. But they hadn’t seen each other in more than three years.

They hadn’t seen their dad, either, not since he shot their mom in the heart.

Stephen Kruspe had spent that time in the Palm Beach County Jail, charged with premeditated first-degree murder. His case had been delayed by clogged courts and COVID-19.

Now, on Sept. 29, 2020, he was finally having a bond hearing.

As a bailiff opened the doors to Courtroom 10F, Steve’s children took their sides.

Stephanie, 42, greeted the prosecutor who said her dad was too dangerous to be out on house arrest.

Matt, 40, shook hands with the defense lawyer. They hoped for bail, so Steve could await trial at home with Matt’s family.

Two deputies led in Steve, now 66, shuffling in ankle shackles, his wrists handcuffed in front. His gray sweatsuit seemed to swallow his thin frame. Oversized glasses magnified sunken eyes.

“Mr. Kruspe, how are you?” asked Judge Caroline Shepherd.

He nodded and said softly, “OK.”

He had confessed to the crime, then pleaded not guilty.

He faces life in prison.

“He wants his story told,” said his lawyer. He wants a jury to know not just what he did — but why.

A spotless record

Steve is a decorated Marine and retired teacher who helped raise three kids. Both of his sons became Marines. He worked with troubled youth, trained police officers and was married for 42 years. He had no criminal record.

He told police he killed his wife, Pam, because she had Alzheimer’s and didn’t want to live like that, because he loved her and couldn’t stand to see her suffer. He said he was willing to sacrifice anything to give her peace.

After turning himself in, he told a detective, “I’ve lost my sense of honor.”

“Are you hurt in any way?” the detective asked.

Steve said, “Broken heart.”

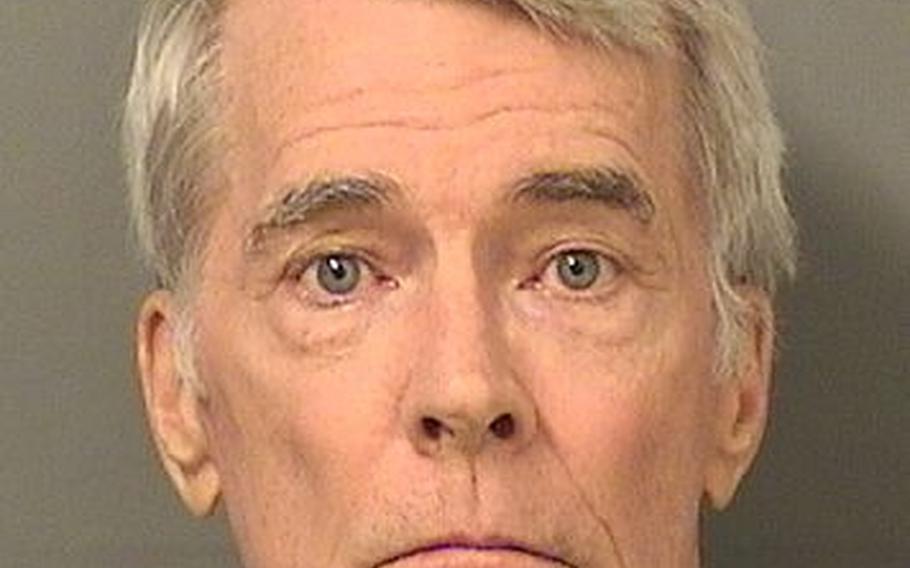

Stephen Kruspe, 65, appears at his first appearance before a judge after the March 27, 2017, shooting of his wife, Pamela, at a Boynton Beach assisted living facility. (South Florida Sun Sentinel/TNS)

‘Like a horror story’

Because of the pandemic, many people had to testify remotely at the bond hearing. A screen on the back wall at the Palm Beach County Courthouse showed 24 boxes of witnesses waiting to weigh in from across the country.

A forensic psychologist, Marine general and several co-workers planned to speak about Steve’s state of mind and character, how he wouldn’t be a flight risk.

His oldest son, daughter, nephew and sister-in-law were listed as witnesses for the prosecution.

That morning, the state had offered Steve a plea bargain: Admit to a lesser charge of second-degree murder with a firearm and be sentenced to 25 to 30 years.

He would be in his 90s by then. He turned it down.

Prosecutors opened the hearing by playing the 911 call, the account Steve gave the dispatcher. In the chair beside his lawyer, he stared straight ahead.

“And you say your wife is beyond help?” the operator asked on the recording.

Steve blinked behind his glasses as he heard himself say, “Yes, ma’am.”

Boynton Beach Detective Charles Ramos, who first interviewed Steve, took the stand.

“Did he admit he knew what he was doing was wrong?” the prosecutor asked.

Yes, said the detective.

“Did he ever indicate it was an accident?”

No.

Then Steve listened to himself try to explain. “For months, she had been telling me … the anguish she was going through … just unbelievable … like a horror story … She said, ‘I don’t want to be here. I want to die. I want you to kill me.’ ... It went on and on. I couldn’t take it anymore.”

Questions unsaid

In jail, Steve has his own cell in the medical ward, where nurses monitor his depression. He serves lunch to the other inmates, talks to the guards, counsels young veterans. His friends send him books on history, politics, philosophy. He calls them sometimes, and they discuss what he’s reading — until his 15 minutes are up.

They often talk about the past and Pam.

But never about what happened.

Matt Kruspe poses with the ashes of his mother, Pam Kruspe, in his home in Lake Worth, Florida. (John Pendygraft)

His two oldest children don’t want anything to do with him. But his youngest son, Matt, drives an hour every Thursday to see his dad’s face through the video monitor.

He has so many questions he doesn’t feel he can ask — not with the jail’s recorder running. So Matt tells his dad stories about his 12-year-old twins’ soccer games, his wife’s job at the bank, their boisterous pit bull.

Those questions don’t really matter now anyway, he says. His mom is no longer hurting. “She’s up in heaven running marathons, telling Jesus to catch up.”

‘Sacrificed salvation’

At first, Matt said, he’d been furious. He felt betrayed.

When his dad called from jail that first night, he hung up. When his dad called back, he hung up again.

How dare he steal what was left of his mom? And without warning?

But after a few days, Matt said, he started to understand. After all, he’s a combat veteran, too.

“The military tend to view death differently than most people. Death is part of your job,” he said. “Is it justifiable? Were you defending or protecting someone? It gives you the ability to take the emotion out of the process.”

While Matt was fighting the Taliban, he did his duty but kept thinking about the enemy soldiers’ wives and kids. Since his mom died, he said, he’s been questioning his morality and spirituality.

“How do you balance Dad did something wrong vs. Dad saved my mother?”

Matt knows some people question Steve’s method. But to Matt, his dad did the most humane thing: make the end clean and quick.

Suffocating his mother with a pillow, or plying her with pills, Matt said, would have been much worse.

His mom must have been desperate, he said, to have begged his dad to help.

Both of his parents were devout Catholics, which means his dad sacrificed salvation.

Matt said, “He gave that up for my mom.”

He has never heard his dad say he was sorry.

“If he had to do it again, he’d do it again,” Matt said. “And I’d be OK with that.”

‘The greater good’

Prosecutor Reid Scott called Steve a selfish coward, a murderer playing God.

Defense attorney Chris Haddad painted him as a hero, rescuing the woman he loved from unbearable anguish.

“His record is exceptional,” retired Marine Gen. Mark Birches testified. “Top 1 percent of the Marine Corps.”

“Objection,” called the prosecutor. “Irrelevant.”

The judge overruled.

Five people swore that if Steve were let out on bond, he wouldn’t be a flight risk. His friend Kent Bolin’s wife, Deb, testified that she’d invited him to stay with them. So did a fellow teacher. “To think that the act was in any way done with malice or violence,” said Jonathan Todd, “that borders on the impossible.”

Matt’s wife, Letoria, said their children understand what happened and miss both of their grandparents. She said she’d be happy to have Steve in their home. She had helped sell his house, and the money from that would cover a $250,000 bond. She said, “I believe he’s trustworthy.”

The defense introduced Steve’s glowing military reviews, citations and endorsements — and letters of recommendation from two dozen people, many fellow Marines, who wrote that Steve’s act was merciful.

There also were thank-you letters for Steve’s civilian service: training police officers in Lake Worth, Palm Beach, St. Lucie County. A Florida congressman commended him for his work on the Jupiter Lighthouse. The Boy Scouts thanked him for his leadership.

Steve’s lawyer said, “These all show how he contributed to the greater good.”

When you kill someone, should the life you’ve lived matter?

Stephen Kruspe, 62, of Lake Worth, Fla., is accused of fatally shooting his wife. (Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Officd)

‘Where was his loyalty?’

On the way to the witness stand, Stephanie passed within a few feet of her dad. She didn’t look at him. He hung his head.

She carried a printed statement titled, “This Is My Father.”

Before she started reading from it, she told the judge that her brother Matt had guns, and she was worried about her dad being there. “In his mental situation, he could do damage to the children, to my brother and sister-in-law.”

He might be suicidal, she said.

Stephanie and her mom had been close, and ran races together. Her mom babysat her kids.

She had lived 90 minutes away from the assisted living facility and said she visited twice a month. Toward the end, she didn’t feel safe taking her mom out alone.

She knew how sick her mother was, but Stephanie testified that she’d never heard her express a wish to die.

Her dad had other options, she said.

“He could’ve put her in that home and walked away if things got too difficult. We would’ve made sure she was taken care of.

“He chose to take matters into his own hands to make it go away.”

She turned to her paper, then stopped and stared at her dad, who was looking at his lap.

“He is not capable of doing what’s recommended when faced with adversity,” she said angrily. “To have and to hold, for better or for worse, in sickness and in health is not demonstrated by a .45 to the chest.”

Next, her older brother, Andrew, video called from Alabama. He was a percussion instructor in the Marines and now teaches music. He also had written a letter.

In 2016, he said, a year before his dad shot his mom, he flew to Florida. Andrew said his dad told him and his sister, “I wish I could just put a round in her chest and put her out of her misery.”

“We thought he was just saying this out of frustration with her condition,” he testified. “Until he wasn’t.”

He called his dad irrational, unpredictable, deceptive. His dad prided himself on his code of ethics. “But where was his loyalty to my mother?” Andrew asked. “Those things that were offered to defend him also showed he should’ve treated my mother with more respect.”

His dad is exactly where he belongs, Andrew said.

He echoed concerns for Matt’s family.

Pam’s sister wrote a letter saying Steve is dangerous, lacking impulse control “and the necessary emotional intelligence to know that in society it is never appropriate to take another person’s life when the person is mentally incapacitated.”

Having known Steve for 44 years, Paula Purdy described her brother-in-law as petty, spiteful, deceptive and a know-it-all who always has to have the last word. “He is not the upstanding, honorable person that the defense is attempting to paint him as,” she wrote. “The bullet Mr. Kruspe chose to end my sister’s life with has ricocheted around the family causing immense pain, testing relationships, and left us reeling as to how one person’s selfishness can cause so much destruction.”

Please, she wrote, “let’s not romanticize the acts of a murderer and spin it into a Shakespearian tale that never actually existed.”

Matt understood his siblings’ feelings but felt they were misinterpreting their dad’s motive. And he wondered: Where had some of these relatives been all this time? These people who said they worried about his kids, they hadn’t been checking in.

Regular phone calls had turned to infrequent texts. They had lost family Thanksgivings, Christmases, birthdays. Their kids were growing up without their cousins.

Matt had tried to tell his brother and sister he understood their feelings. But he felt they weren’t willing to see his side.

He hadn’t planned to testify. But now he felt he had to.

From the stand, he met his dad’s eyes, then turned to the judge. “A lot of people have expressed concerns today about our safety. But no one ever asked about me or my family’s well-being,” he said.

He sounded hurt. He said he and his wife didn’t have any concerns about his dad moving into their home. Neither did their kids.

“It was their idea.

A 62-year-old man who fatally shot his wife who was suffering from dementia told investigators she had asked him to kill her. (South Florida Sun Sentinel/TNS)

‘Absolutely tragic’

Steve didn’t take the stand. While his children and others talked about his character, he never reacted.

After four hours and final arguments from the lawyers, Judge Shepherd called a recess.

Florida doesn’t allow any aid in dying, even for terminally ill patients. Killings by caregivers are rare, often linked to stress, and have drawn a wide range of reactions from judges and juries. But here in Florida, state statutes consider “assisting self-murder” to be manslaughter.

Even so, Shepherd didn’t have to determine a verdict yet — only whether to let Steve out until the trial.

After a half-hour, she returned and called the circumstances of the killing “absolutely tragic.”

But she worried that Steve was a flight risk and ruled that he had to stay in jail.

Matt, deflated but not surprised, lingered to talk to his dad’s lawyers.

Stephanie and her husband left the courthouse quickly, without looking back.

A delay and a divide

During the last 15 months, while Stephen Kruspe has waited in jail, his children have not talked. Matt said his sister and brother have texted a couple of times, but they’re not really in touch.

Matt still visits his dad most Thursdays. Steve’s friends still send him books.

He has been in jail for almost five years. His trial was scheduled to start this month in Palm Beach County. But on Jan. 4, it was postponed again.

The next time Steve will see his children, they will be on opposite sides of the courtroom.

However the jury rules, Matt knows that his relationships with his siblings and his mom’s family likely will never be repaired.

He feels the gulf between them growing.

Caregiver killings

No state or federal agency tracks data about caregivers who kill their patients. But University of South Florida professor Donna Cohen researches violent deaths and homicide-suicides in the Department of Child and Family Studies.

In her research on 116 family caregiver killings in the U.S. from 2010 to 2015, she found that most of the crimes were committed by men, and most of the victims were older women. About two-thirds of the caregivers also took their own lives.

“Their decision-making becomes impaired by overwhelming stress, depression, anxiety, physical exhaustion, extreme frustration … and isolation,” Cohen wrote.

She said that pressure left them feeling hopeless and helpless.

U.S. law, she points out, does not distinguish between caregivers who kill with compassion and those with other motives.

But she found “significant variability” in the way those cases were handled.

Roswell Gilbert, 75, had been married to Emily for 51 years. She had Alzheimer’s and osteoporosis and was in pain, he said. So in 1985, he shot her twice in their Lauderdale by the Sea home. A jury convicted him of first-degree manslaughter, and he was sentenced to the minimum 25 years. But five years later, then-Gov. Bob Martinez gave him clemency, saying he was too old and ill to remain in prison.

Wayne Juhlin, 94, said he killed his wife, Jacqueline, 80, in their Venice home in 2019 because she was suffering from dementia. He tried to shoot himself afterward, he told police, but the gun malfunctioned. So he called 911. Prosecutors initially charged him with first-degree murder, then dropped it to manslaughter with a weapon. In February 2020, he got out on bail and went to live with his daughter in Missouri. In July 2020, all charges against him were dropped.

Manuell Chance, 81, said his wife, Joyce, 81, was trying to kill herself in their Seminole home by overdosing on Klonopin on April 11, 2021. When she didn’t die, he told police, he tried to help by choking her, then stabbing her in the chest with an ice pick, which collapsed her lung and ended her life. As of Jan. 6, he hadn’t been arrested.

©2022 Tampa Bay Times.

Visit tampabay.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.