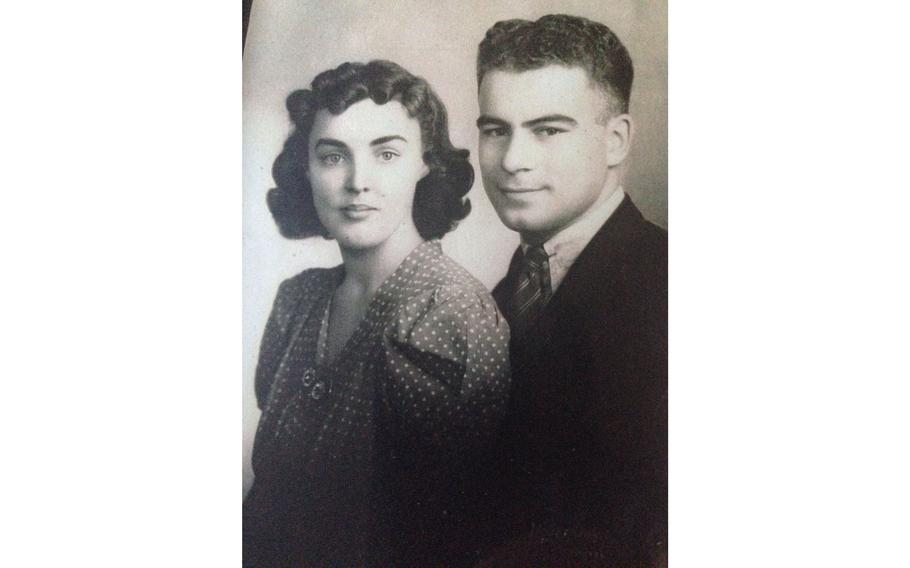

George L. Paradis (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency)

BOULDER, Colo. (Tribune News Service) — Every detail of Oct. 7 is seared into Beverly Carrigan's memory.

She won't forget the sound of taps reverberating through the cemetery; the pink-blossomed tree under which she stood; or the slow funeral salute as her uncle George Paradis was laid to rest at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific.

Paradis died 80 years ago aboard the USS Oklahoma during the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor. He was only recently identified through mitochondrial DNA supplied by Carrigan and her sister. They were contacted in 2015 as the military made a final attempt to identify the remains of the Oklahoma's crew.

Carrigan, a longtime Boulder resident living in the Frasier Meadows retirement community, said they were happy to provide DNA, but as the years continued on, she all but forgot she'd done so. That is until February, when she received the call that her uncle had been identified.

Months later, Carrigan flew to Hawaii with her son and daughter, to officially honor the man she remembers as a husband and father, her smiling uncle who hoisted her on his shoulders and who once set fire to their home after he fell asleep with a lit cigarette.

"I'm the only person in the world who remembers this man," Carrigan said, noting her younger sister was 2 years old on the day of the attack.

Much like her memory of her uncle and of the day he was buried earlier this year, Carrigan remembers the Pearl Harbor attack with impressive clarity, considering it happened 80 years ago.

After attending Sunday morning church services with her family, Carrigan went to a friend's birthday party. The friend's father was a pressman for the Los Angeles Herald-Express and he was able to list the ships that had been hit in the attack, Carrigan recalled.

"I remember picking up the phone — here I am 11 — calling my mother and saying Uncle George's ship went down," Carrigan said. "I remember it very clearly."

While in Hawaii in October, Carrigan was overwhelmed by the love and compassion she experienced. She was moved by the amount of thought and consideration that went into the event.

"Once the bones were found, I didn't expect to have such a military ritual," she said. "That really took me back, that they were so generous and it was so beautiful and so respectful."

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), the entity tasked with recovering United States military personnel who are listed as prisoners of war or missing in action, provided Carrigan and her family with a certificate that included a photo of Paradis.

It was signed by Rear Admiral Darius Banaji, the DPAA's deputy director of operations.

"We in DPAA are deeply honored to have helped bring your uncle home and to provide your family long sought answers," he wrote.

When her uncle's remains were identified, the military told Carrigan she could bury Paradis anywhere she wanted. She decided he should stay in Hawaii at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, known informally as the Punchbowl.

The military also said she could bring two direct blood relatives to attend the service. She chose her son Patrick, since he lived in Honolulu for a while, and her daughter Sheila, since she named her child Paradis after the family name.

Originally, Sheila Carrigan said she wasn't certain about the military spending money to fly her family out and hold a funeral service for her uncle. But her opinion changed once she experienced it.

"It brought home to me the cost of war," she said. "I think of this 23-year-old guy who never got to live his life."

It would have been a teary affair for her mother, had she lived to see the day Paradis was laid to rest, the elder Carrigan said.

"She would be very honored," she said. "She would be overwhelmed."

Sheila Carrigan wore her grandmother's wedding ring to service, as a way for her grandmother to attend and honor the younger brother she so loved.

The experience also reminded her how important it is to keep the stories and memories of older generations alive, to ensure the stories don't die out when the people with direct experience die.

"From my perspective as a descendent, this is good because this story won't die with her," Sheila Carrigan said. "Because she's the last living person who remembers him. To the extent our children are interested in family history, it will go on."

As the military on Tuesday honors the 80th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack in a formal ceremony at the Punchbowl, it marks the end of DPAA's six-year USS Oklahoma Project. The project identified 92% of the 429 sailors and Marines who died aboard the ship, one of six ships that sank or was destroyed in the attack.

For Beverly Carrigan, the effort is an impactful one.

"It's not only for the families," she said. "It's for the country."

(c)2021 the Daily Camera (Boulder, Colo.)

Visit the Daily Camera (Boulder, Colo.) at www.dailycamera.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.