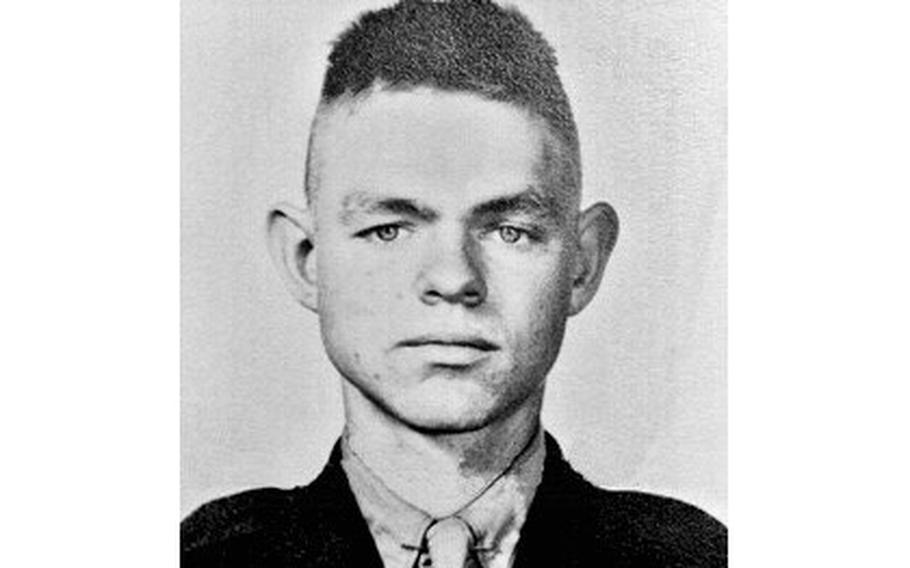

Pfc. Royal L. Waltz, 20, was accounted for in May 2019 but the announcement was delayed until after a recent briefing of relatives. (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency)

(Tribune News Service) — World War II veteran Pfc. Royal Waltz’s body was lost to the Marine Corps and his California family for over 70 years.

That changed a couple years ago, after some of his bones were found in 2013 on the remote Pacific islet of Betio, and then matched with unknown remains interred decades ago in Hawaii, resulting in Waltz’s identification in 2019.

This week — 78 years after the 20-year-old Marine was killed — his remains finally returned home to the central San Joaquin Valley, where he grew up before moving to the Central Coast while in high school.

The coffin holding his remains was received on Thursday morning by his family — a niece, great-niece, and cousin — at the Los Angeles International Airport, then driven north to Hanford ahead of a Monday funeral for him in that Valley city.

A burial will follow at the Grangeville Cemetery in nearby Armona, where he will be laid to rest with full military honors near his mother, siblings and other family.

“There were so many boys lost in all our wars,” said Waltz’s niece, Patricia Hanse Verheul, “and so many didn’t make it home. ... What an honor it is to be allowed to receive his remains and bury them as a family. It’s just indescribable.”

World War II vets’ bodies lost on island after Battle of Tarawa

Betio, where many of Waltz’s remains were lost and forgotten, is not a tropical paradise, said Justin LeHew, a retired Marine and chief operating officer of History Flight, the nonprofit that found Waltz’s bones on that Pacific island in 2013.

It’s “more than a third-world country,” he said, coupled with extreme heat and humidity where the WWII graves “were lost under pig sties, under public toilets.”

The sand above where Waltz’s remains were unearthed tells a sad story.

Digging into it, the first layer reveals buried trash, LeHew said. Deeper, it’s crushed coral, used by the U.S. military in the 1940s to make an airstrip during World War II. And below that, it’s black soil, scorched during the Battle of Tarawa, when Waltz was killed. The island was on fire for 76 hours in November of 1943, LeHew said.

“Then under that is the most beautiful, pristine white sand you’ve ever seen in your life,” LeHew continued, “and that’s where all the Marines are at, and undisturbed.”

Betio, where they died in the Tarawa atoll, part of the Gilbert Islands, is around two miles long and half a mile wide. That tiny piece of land in the Pacific Ocean was the most fortified atoll America invaded during the Pacific Campaign — an invasion that became one of the bloodiest battles in the Pacific.

More than 1,000 Americans, and thousands more Japanese and Koreans, were killed during the Battle of Tarawa.

The bodies of more than half of those Americans killed in the Battle of Tarawa still weren’t accounted for many decades after the war. That fact startled the founder of History Flight. It resulted in the organization shifting its mission from taking veterans on plane rides to searching for the remains of those missing in action.

History Flight has recovered over 250 sets or portions of remains from Tarawa since 2010 — in some cases, complete skeletons — that were then delivered to the U.S. military. Of those, over 130 have been identified, LeHew said.

After the Battle of Tarawa, some graves were relocated so the Navy could build a runway for aircraft, LeHew said. Later identifications were further complicated by the military setting out white memorial crosses in neat rows on a beach in Betio — photographed and shared widely in the U.S. — each bearing the name of a young man killed in the battle, but “none of the names corresponded to anyone,” LeHew said.

After the war, portions of skeletons were taken from graves for identification, but many weren’t found and were left behind. The remains of around 400 Americans killed in that battle remain unidentified, LeHew said. Many may still be on Betio.

“The most heartbreaking telegrams and letters I’ve seen in my life is after 1949, when the government sent final letters (to families of those missing in action) and said, ‘We’re no longer looking for your sons. We’re no longer putting resources to this. He’s gone.’ I can’t imagine what that would have been like,” said LeHew, a retired sergeant major who did multiple tours in Iraq. “In the military I was in, there was no end, no shutting the door. You don’t leave fallen comrades behind.”

Searching for MIA military service members around the world

The U.S. military experienced a big shift in ethos in the 1970s, following the Vietnam War.

“Decades ago, after WWII and after the Korean War and going into the ‘60s, this mission didn’t exist,” said Sgt. 1st Class Sean Everette, a spokesperson for the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, a branch of the U.S. Department of Defense. “We didn’t have a dedicated agency within the DoD that would go and try to find and recover still-missing service members.”

Today’s DPAA has only been around since 2015, but had similar predecessors that went by other names. The agency has partnered with more than 40 organizations to look for the remains of missing veterans around the world, Everette said. It’s a huge mission.

“Over 81,600 service members are missing from all our modern wars and conflicts back to World War II,” Everette said. “We estimate 38,000 of those are recoverable. The ones not recoverable, many of those were losses at sea, Navy ships that were sunk in with all crew members aboard, or planes that crashed in the water and are currently too deep for us to safely be able to do a scientific archaeological excavation.”

He said most of the missing are from World War II. The military was able to identify around 130 missing service members this fiscal year, 120 last year, and 219 in the 2019 fiscal year, Everette said.

LeHew said 20% of all the military’s missing-in-action identifications are tied to remain recoveries conducted by History Flight, which now does this work in multiple countries.

War’s painful effects through many generations

History Flight’s discoveries on Tarawa prompted the reexamination of 94 sets of unknown remains from that island that had been moved to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii.

Waltz’s remains there in Oahu, previously just known as X-228, were disinterred in 2017 and then matched with those found in 2013 by History Flight. Putting those pieces together resulted in a nearly complete skeleton. New DNA submitted from Waltz’s niece, Verheul, helped make his 2019 identification possible. The sole of a boot and a belt buckle were also identified as belonging to Waltz.

Verheul was born two years after her uncle was killed in Tarawa. She didn’t have to know him to feel the pain of his loss, passed down through generations of her family. Her mother was Waltz’s older sister.

“There was just a sense of loss,” Verheul recalled. “I was a little kid, they didn’t talk about it with me, but I knew Uncle Royal was missing and gone and there was a hole in their lives. ... My grandmother, it hurt her heart all the rest of her life.”

Waltz’s great-niece, Cindy Garcia, was born decades later and still feels that collective pain. Her father was born a month after Waltz enlisted in the Marine Corps. The middle name he was given, Royal, was in honor of his uncle.

She’s been doing a lot of research into his past.

There was confusion immediately following the Battle of Tarawa about what happened to Waltz. Early reports to his family was that he was wounded in a hospital. They got a certificate from the Marine Corps a year after the battle stating that Waltz was “officially declared killed in action.”

The following year, in 1945, they got another letter from one of Waltz’s friends, a fellow Marine at the Battle of Tarawa, who shared more information.

“Your son was wounded in the initial landing,” his letter explains. “The best I can remember he was hit in the shoulder. The fighting was so thick and hot, that he was put in a hole just off the beach. I am sure he received medical attention, because he was to be evacuated as soon as it was possible. When he was going from there to a boat at the beach, he was killed by sniper fire. I don’t know where he was buried.”

Having his remains finally found and identified means a lot to his surviving family, who received his remains on Thursday with the memory of their deceased loved ones, including Waltz’s parents and siblings, close to their hearts.

“The amazing thing is how close our family has become as a result of this,” Garcia said. “The interactions we’ve been able to share. The tears we’ve been able to cry, just talking. We’re each sharing our own heart. ... It’s really special what it’s created, new connections and deeper connections.”

Hanford recalls young man’s ties to central San Joaquin Valley

Waltz experienced other battles before Tarawa. The carpenter and then engineer in the Marine Corps also fought at Pearl Harbor and the Battle of Guadalcanal.

He was tall and strong, and described boot camp in San Diego, not long after enlisting in 1941, by saying, “This life is much easier and we have more time to ourselves,” in a letter to his family.

He ended it, “Don’t work too hard and remember to eat candy for me. Your appreciating son, Royal Lawrence Waltz.”

His family is looking forward to honoring him during a funeral service at 10 a.m. Monday, Sept. 27 at First United Methodist Church in Hanford. Verheul said masks will be required, and there will be limited seating because of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

His burial will follow at Grangeville Cemetery in Armona. His remains arrived at a funeral home in Hanford on Thursday afternoon after being flown from Hawaii to Los Angeles.

“My family and I are amazed at the amount of recognition Uncle Royal is receiving — from the church historian, to the pastor who has sanded and varnished the church doors, to people we don’t know that feel a connection to the process of recovering our missing soldiers,” Verheul said.

That church historian, Jim Gregory of First United Methodist, has been doing a lot of research into Waltz’s connection to the Valley. Waltz grew up on a dairy farm in the Hanford area, and his family’s ties to the area go back to the 1800s.

One of First United Methodist’s stained glass windows was previously dedicated to Waltz and his parents. Waltz was a member of that church, and was elected president of its youth group. He had Methodist minister ancestors on both sides of his family.

Waltz attended elementary school between Armona and Lemoore in a now-gone school district that’s now part of Central Union School District, Gregory said, and then finished grammar school in Grangeville, also in Kings County. He attended Hanford High School until his family moved to Cambria, where his uncle worked for a newspaper and his father got into the real estate business.

Waltz’s parents moved back to Hanford in the early 1950s.

Verheul is very grateful Waltz will be buried at the Grangeville Cemetery near many family members.

“It makes it all that much more meaningful,” Verheul said, “because there is that history and that link. I know the cemetery. I know where we’re going to put him, and I know who’s next to him. It’s just comforting to be so close to him and to know that it’s home.”

(c)2021 The Fresno Bee (Fresno, Calif.)

Visit The Fresno Bee (Fresno, Calif.) at www.fresnobee.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.