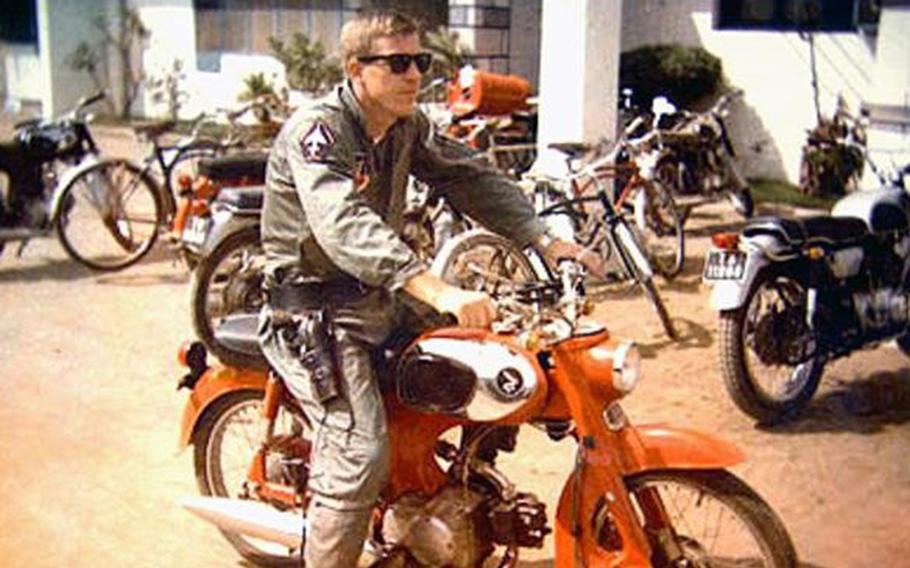

Air Force Col. Warren Anderson sits on a motorcycle in South Vietnam in this photo taken in 1965. He went missing about a year later when his RF-4C reconnaissance jet went off radar during a scouting mission over North Vietnam. (Natalie Rauch)

JOINT BASE PEARL HARBOR-HICKAM, Hawaii — On April 26, 1966, Col. Warren Anderson and copilot Maj. James Hale Tucker took off in their Air Force RF-4C reconnaissance jet for a routine scouting mission over North Vietnam.

They went off the radar and were never heard from again.

Anderson’s daughter, Natalie Rauch, was just 8 when he went missing. Her mother never remarried and raised Rauch and three younger children by herself.

Rauch, who has lived in Honolulu since 2014, has over the years come to accept the reality that her father’s remains will likely never be found, because so little is known about where the jet went down.

That is a big part of why the annual National POW/MIA Recognition Day is of towering importance to her and the thousands of other family members whose lives were forever changed by the unresolved loss of someone in uniform.

On Friday, Rauch was the keynote speaker at a ceremony at the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency on the joint base marking the day, which is intended to honor those held as prisoners of war and those who remain missing.

“I feel like every time I have the opportunity to represent my dad, I hope I come across as composed,” she said during a media roundtable Thursday at DPAA’s headquarters. “But then, at the end of it all, I feel like I’m still that 8-year-old kid waiting for her dad to come home.”

Natalie Rauch, whose father went missing during an Air Force mission over North Vietnam in 1966, talks with reporters at the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Thursday, Sept. 16, 2021. (Wyatt Olson/Stars and Stripes)

DPAA is the agency tasked with finding, retrieving and identifying the missing dead from World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War — and the mission is vast.

“Today, more than 81,900 U.S. personnel remain unaccounted for — including more than 72,000 from World War II, more than 7,500 from the Korean War, and more than 1,500 from the Vietnam War,” Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said during a ceremony in the Pentagon on Friday. “Many of the missing are lost deep at sea, but our experts estimate that some 38,000 may be recoverable.

“So we still have a lot of work to do.”

Precautions over the coronavirus have curtailed the number of missions DPAA has been able to send into Southeast Asia since the spring of 2020, said Johnie Webb, the agency’s deputy director for outreach, during the roundtable.

DPAA, however, has helped stand up six teams in Vietnam staffed by locals that have continued work during the pandemic, Webb said.

“I wish we could do more, and I wish we could do it quicker, but we have to work within the limitations that we face on a daily basis,” said Webb, a veteran of the Vietnam War.

The agency’s previous iteration, the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command, came under fire for mismanagement and a sluggish pace in making identifications, and the accounting effort was reorganized into the DPAA in 2015.

The agency had slightly surpassed its annual target of 200 identifications in fiscal years 2018 and 2019, but the total plummeted to 120 for the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30, 2020. It has projected making 200 identifications by the close of this fiscal year.

DPAA is now winding down a years-long effort to identify the disinterred remains of sailors and Marines who died aboard the USS Oklahoma at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, and then buried as unknowns in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu.

As of Wednesday, DPAA had identified 346 of the 394 crew members who had been buried as unknowns.

The agency is “doing more with less” because advances in DNA capabilities can be used on ever tinier and decayed bone samples, Debra Prince Zinni, deputy director of DPAA’s laboratory, said at the roundtable.

The agency was recently accredited to use isotope analysis, she said. Isotopes found in bones reveal, among other things, an individual’s diet and whether it is particular to a given geographical location.

However, no amount of technology is useful if remains cannot be found, and that is the sort of limbo that Rauch and others like her learn to live with.

Acceptance comes in waves.

Audience members render honors during a National POW/MIA Recognition Day ceremony at the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency facility on Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii, Friday, Sept. 17, 2021. (John Miller/U.S. Army)

When the Vietnam War was over and Hanoi released the U.S. prisoners they had held for years, hope Rauch held that her father would be among them was dashed.

In 1978, the status of her father and Tucker was changed to Killed in Action/Body Not Recovered.

Anderson’s name is on a gravestone at Arlington National Cemetery, etched into the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall near the National Mall and engraved on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific.

But no part of him has come home, and Rauch has spent her life gathering remembrances, like pieces of a puzzle, from people who knew him.

“I’ve had to make my own peace,” she said. “Because I don’t want to run around being angry. I don’t want to run around being distraught, bitter. It would be a waste of my time, and no one’s going to want to spend time with me.

“So, I’ve made my own peace that if I don’t find an answer, it’s OK,” she said, pausing a moment. “But I still want DPAA to keep working.”