Tim Kennedy, a U.S. Army Green Beret and a mixed martial artist, takes a photo of himself and evacuees inside a U.S. military cargo plane, in an undated photo taken during the evacuation of at-risk people from Afghanistan in the last two weeks of August 2021. Kennedy traveled to Kabul, Afghanistan as a private citizen affiliated with an ad hoc volunteer group that formed to help evacuations. (Nick Palmisciano)

Veterans and civilians who worked tirelessly to help Afghans escape Taliban rule are now agonizing over the fates of friends and allies left behind in the wake of the U.S. military’s withdrawal, which was completed Monday.

Although the hurried efforts brought more than 123,000 civilians from Afghanistan on U.S. and coalition aircraft, not everyone the U.S. wanted to evacuate made it out of the country, said Marine Gen. Frank McKenzie, head of U.S. Central Command.

“There's a lot of heartbreak associated with this departure,” McKenzie said.

Volunteers served as conduits between at-risk Afghans and the U.S. government during the evacuation. Some even flew to the Kabul airport to help.

“We knew it was going to end in tears from the very beginning,” said Nick Palmisciano, an Army infantry officer for six years, in a Twitter direct message Tuesday. “It was a hard pill to swallow, but it is the very reason we pushed so hard.”

Palmisciano said he worked to bring 12,000 people out of the country with a large a group of volunteers that had a base of operations in Washington, D.C., and its own hangar at the Kabul airport.

A group of U.S. military veterans and civilian volunteers gathered for an undated photo as part of an effort to evacuate at-risk Afghans. The group helped bring 12,000 people out of Afghanistan, said Nick Palmisciano, an Army infantry officer for six years, adding that they had people based at a hangar at Kabul’s international airport and at the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C. (Nick Palmisciano)

But so many people who helped the U.S. remain in Afghanistan despite volunteer efforts, said retired Col. Mike Jason, the interim executive director of an informal group called Allied Airlift 21.

“Let’s face it,” Jason said. “The numbers indicate most of us failed to get them out, most of us failed. So how do we deal with that?”

Jason said he is worried about the mental health of the veterans and civilians who poured their efforts into evacuations.

Allied Airlift 21 evacuated around 600 to 700 people, Jason said, but this was out of a list of over 30,000 who sought their help.

The former battalion commander in northern Afghanistan said his hopes for an orderly evacuation disappeared once he realized how disorganized and chaotic the airport was.

He and other volunteers described a system in which people with adequate paperwork were turned away from the airport, while some people with no documentation or connection to the U.S. got in.

Chris Jones, a Marine veteran, said the process brought back memories of his time as a machine gunner in Afghanistan and the accompanying feelings of helplessness and regret for not being able to save lives.

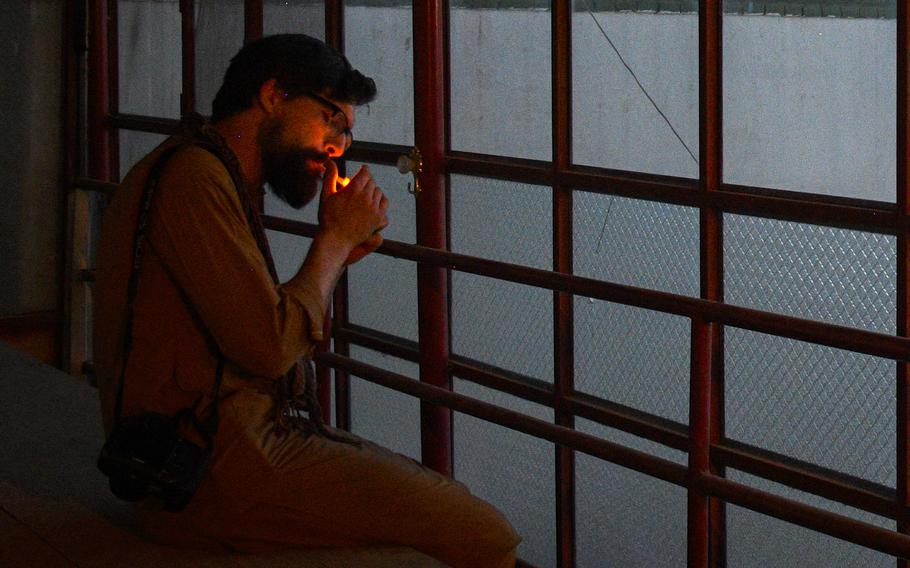

Chris Jones, who fought in Helmand province during two tours as a Marine, lights a cigarette as he watches the sun set on a return trip to the province in 2019. Jones said the process of trying to help evacuate Afghans who worked with the U.S. government brought back memories of his time in Afghanistan, along with feelings of helplessness and regret for not being able to save people. (J.P. Lawrence / Stars and Stripes)

“There are thousands of American veterans who are having to tell the guys who kept them alive on their deployment, ‘I don’t know what to do,’” Jones said.

Jones recalled traveling to Arlington National Cemetery last weekend to pay respects to a friend who died during their first deployment to Afghanistan in 2010.

While at the gravesite, Jones received a text message from an Afghan man who wanted help leaving the country.

“It was surreal to tell a grave, ‘Hey, man, I think we lost this war pretty bad,’ and to have the reality of it thrust into my face, via my phone, and to sit there and to say, ‘I can’t help you,’” he said.

Afghan women tend to a baby in an undated photo taken through a chain link fence at Kabul, Afghanistan’s international airport. While an evacuation effort brought more than 123,000 civilians from the country on U.S. and coalition aircraft, not everyone the U.S. wanted to evacuate was able to leave, said Marine Gen. Frank McKenzie, head of U.S. Central Command, on Aug. 30, 2021. (Nick Palmisciano)

Jones and other volunteers said they still plan to try to help Afghan allies escape, perhaps via land routes to neighboring countries.

Efforts will pivot to welcoming and assisting refugees who have arrived in America, and the lists of Afghans requesting help will be offered to the U.S. government, Jason said.

Air Force veteran Christy Barry was in basic training at the time of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

She said she had believed in the mission of helping Afghanistan, and she signed up for a program in which she learned one of the country’s languages to better assist Afghan forces.

“I’m heartbroken for the Afghans that I couldn’t get out,” said Barry, who deployed to Afghanistan as an Air Force officer and then as a civilian. “Devastated, just gutted, absolutely gutted.”

The next few weeks will be hard for a lot of veterans, Barry said.

She had supported the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan but said the execution was a disaster.

“There’s a part of me that has died,” she said. “A part of me that used to be a patriotic American has died.”