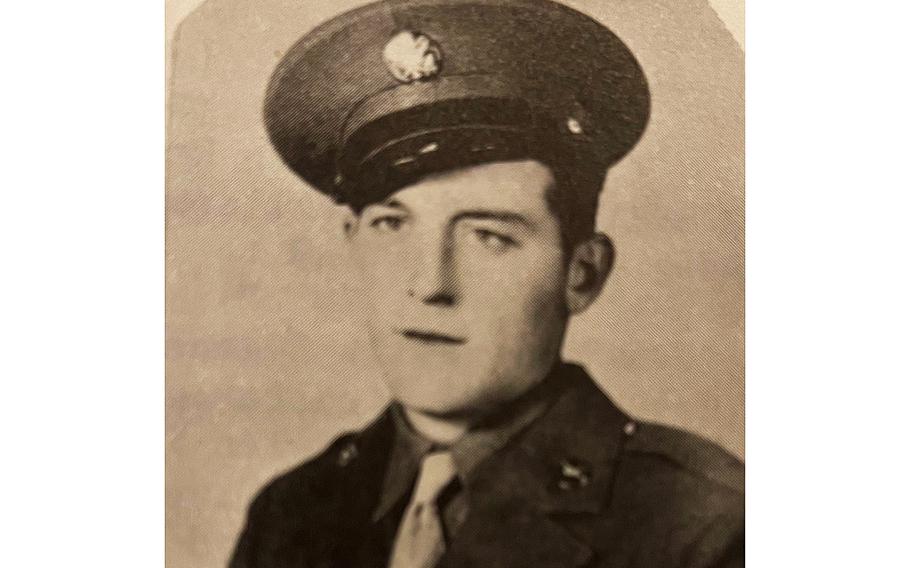

World War II veteran Army Pvt. Warren G.H. DaVault. Davault’s name — misspelled as DeVault on military records as a result of a clerical error — is recorded on the Walls of the Missing at Netherlands American Cemetery, an American Battle Monuments Commission site in Margarten, Netherlands, along with the others still missing from World War II, according to officials. (dpaa.mil)

DAYTON, Tenn. (Tribune News Service) — World War II Army Pvt. Warren Glinn Harding Davault rests peacefully in his hometown after nearly 77 years lying in an unnamed grave in Belgium’s Ardennes American Cemetery and a trip halfway around the world back to Tennessee.

The Rhea County High School senior and athlete was drafted before he graduated and served in the U.S. Army two years before he was killed Nov. 20, 1944, in the Battle of Hürtgen Forest while fighting German forces. Davault, at 24, was among the more than 33,000 American casualties in the costly battle.

Davault and his brothers, Emmett and Cleo, and two brothers-in-law, Roy Marler and Arthur Morgan, all were drafted into the service in World War II, four of them serving in the European theatre and one in the Pacific.

Bill Davault, the late private’s nephew, said Saturday he was glad the family’s long-lost soldier was home at last.

“I was 2 months old when he went in the army,” Davault, 79, recalled as the pews filled for the service.

When he’d grown old enough to remember the questions the mourning family had, Bill Davault said he remembered them talking about “how they missed him and they wondered where he was and wondering if he could still be living, if he survived.”

The mystery wasn’t forgotten by the family.

“Two of his sisters wrote letters to the governor looking for information about the remains, where he might be,” he said. “They didn’t just forget. They kept trying and trying to get information.”

En route to putting a name to the remains in Belgium, family members sent DNA to the military to help with identification and launch the return home, he said.

Davault was assigned to Company F, 2nd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division, according to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. Davault’s unit was engaged in battle with German forces near Hürtgen, Germany, when he was reportedly killed in action. Davault’s body couldn’t be recovered because of the ongoing fighting, and his remains were not recovered or identified, according to an accounting agency news release on Davault’s identification.

During Saturday’s service at First Baptist Church in Dayton, Tennessee, retired U.S. Army Col. H. Brock Harris spoke of Davault’s early life and military career and the price he would pay in service to his country.

Davault, born Sept. 29, 1920, entered the military at Fort Oglethorpe, Ga., on Nov. 14, 1942, and after completing his 13-week initial entry training was assigned to the 12th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division, Harris said, noting the 12th Infantry Regiment’s history traces its lineage back to the Civil War.

Davault spent August 1940 to August 1943 in the 4th Infantry Division, which participated as an experimental motorized infantry unit in the Louisiana Maneuvers, which would later prove successful in combat, Harris said.

“The 12th Infantry Regiment, along with the rest of the 4th Infantry Division, arrived in England on Jan. 29, 1944,” Harris said. “Chosen as the spearhead amphibious division of the D-Day landing on the Normandy coast of France, the men of the 12th Infantry Regiment stormed ashore at H-Hour on June 6, 1944, on a stretch of the French coast named Utah Beach.”

There were relatively few casualties among the 4th Infantry Division, he said.

Then Davault’s division participated in the breakthrough at Saint-Lô on July 25, 1944, and was the first into Paris on Aug. 25, 1944, he said, as well as being the first infantry division moving into Germany on Sept. 11, and the first through the Siegfried Line three days later, Harris said.

He recounted Davault’s final action at Hürtgen Forest, which contained one of the largest wooded tracts in Germany at the time, extending from the northern portion of the Ardennes region of Belgium and Luxembourg to the Eifel region of Germany. It was 20 miles long and 10 miles wide and “contained some of Europe’s most rugged terrain,” he said.

An obstacle belt, the renowned Siegfried Line, ran through the forest and consisted of minefields, dense barbed wire, concrete pillboxes and mile after mile of “dragon’s teeth” — square, pyramidal fortifications against tanks and mechanized infantry. Harris said the Germans used dams to limit the Americans’ movement and block them from crossing the Rhine River.

It was the scene of a series of fierce battles that began in September 1944 and culminated in mid-February 1945, but along the way, Davault would make the ultimate sacrifice.

“Largely unknown by Americans today, this battle was one of the bloodiest, and most disastrous U.S. Army actions of the Second World War,” Harris told those attending Davault’s services Saturday.

“On or about Nov. 8, 1944, 12th Infantry relieved the 109th Infantry after the 109th suffered heavy casualties during its attack that began six days earlier on Nov. 2,” Harris said.

“An eyewitness account of the battle comes from an interview with Mr. Normand Chartier for the New Bedford, Massachusetts, Cable Network series, ‘Heroes Among Us,’” Harris recalled, citing the series. “ Mr. Chartier was both a medic and infantryman in Company F, and he described the Hürtgen Forest as ‘very dark and desolate, occupied by numerous German pillboxes and bunkers manned by machine gunners with itchy trigger fingers.’”

Harris noted Chartier’s recollection that “the worst part of the battle was the constant German artillery barrages that rained down hot metal on attacking American forces,” he said.

“On Nov. 20, 1944, Private Davault lost his life along with several Company F Soldiers and he had just turned 24 years of age,” Harris said. “While we do not know the exact cause of death, we can conclude that overwhelming firepower in the form of German artillery strikes was the most likely cause of his death.”

Efforts to recover remains that could be positively identified after the battle were unsuccessful, so Davault’s remains, along with those of several others, were interred at the Ardennes Cemetery in Belgium, he said.

During the Hürtgen Forest battle, Company F had 106 casualties, Harris said, noting an infantry company of the day was typically comprised of 150 men.

Davault’s awards and decorations include the Bronze Star, the Purple Heart, the Combat Action ribbon, the American Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, the World War II Victory Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, the Army Service ribbon, the Overseas Service ribbon and the Combat Infantrymen’s Badge, Harris said. The 12th Infantry Regiment was also awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for its defense of Luxembourg and the Belgian Fourragere, he said.

After Harris’ words and a presentation to the family, “Amazing Grace” was sung a cappella to a solemn room.

The words “I once was lost, but now I’m found,” seemed to take on a special meaning Saturday as Davault’s casket stood draped with an American flag in the church sanctuary. And when Brenda Morgan sang the last line, the church filled with more than 100 people was completely silent.

Following the end of the war, the American Graves Registration Command was tasked with investigating and recovering missing American personnel in Europe and conducted several investigations in the Hürtgen area between 1946 and 1950, according to the agency. But investigators were unable to recover or identify Davault’s remains.

He was declared non-recoverable in January 1952.

While studying unresolved American losses in the Hürtgen area, an accounting agency historian determined that one set of unidentified remains, designated X-5429 Neuville, recovered from the Hürtgen Forest in 1947 possibly belonged to Davault. The remains had been buried in Ardennes American Cemetery in 1951 and were disinterred in April 2019 to be sent to the accounting agency laboratory at Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska, for identification, officials said.

To identify Davault’s remains, accounting agency scientists used dental and anthropological analysis, as well as circumstantial evidence. Scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System also used mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosome DNA analysis, officials said.

Davault’s name — misspelled as DeVault on military records as a result of a clerical error — is recorded on the Walls of the Missing at Netherlands American Cemetery, an American Battle Monuments Commission site in Margarten, Netherlands, along with the others still missing from World War II, according to officials.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee issued a proclamation on Tuesday declaring Aug. 14 a day of mourning in remembrance of Davault.

Davault’s return home after more than three-quarters of a century offers hope to other families of lost veterans.

“What it really means is showing honor to him and giving the other folks who lost loved ones in the war, any war, the opportunity to have hope that they can get their family member back because we’re the only country in the world that searches for our lost soldiers,” Bill Davault said.

(c)2021 the Chattanooga Times/Free Press (Chattanooga, Tenn.)

Visit the Chattanooga Times/Free Press (Chattanooga, Tenn.) at www.timesfreepress.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.