Flags fly at Veterans Health Care Center of the Ozarks on Aug. 22, 2019. (Bonnie Jo Mount/The Washington Post)

Oversight failures, a fearful workplace culture and lax quality standards for years at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Arkansas allowed a pathologist, Robert Levy, who was routinely drunk on the job to misdiagnose thousands of veterans — sometimes with dire or deadly consequences, a new investigation has found.

Hospital leaders "failed to promote a culture of accountability" that would have led more of the doctor's colleagues to come forward with accounts that his behavior was putting patients at risk, according to the report released Wednesday by VA's Office of Inspector General. But the staff members at the Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks in Fayetteville feared that reporting their concerns would lead to retaliation from their bosses.

"Any one of these breakdowns could cause harmful results," Inspector General Michael Missal's staff wrote in an 86-page report about the failures to stop the pathologist. "Together and over an extended period of time, the consequences were devastating, tragic, and deadly."

For more than a decade, hospital officials led by Levy's supervisor, former chief of staff Mark Worley, ignored red flags that allowed the pathologist to make tragic mistakes, delaying medical care for cancers and other illnesses for some veterans and leading to unnecessary treatment for others, the report said.

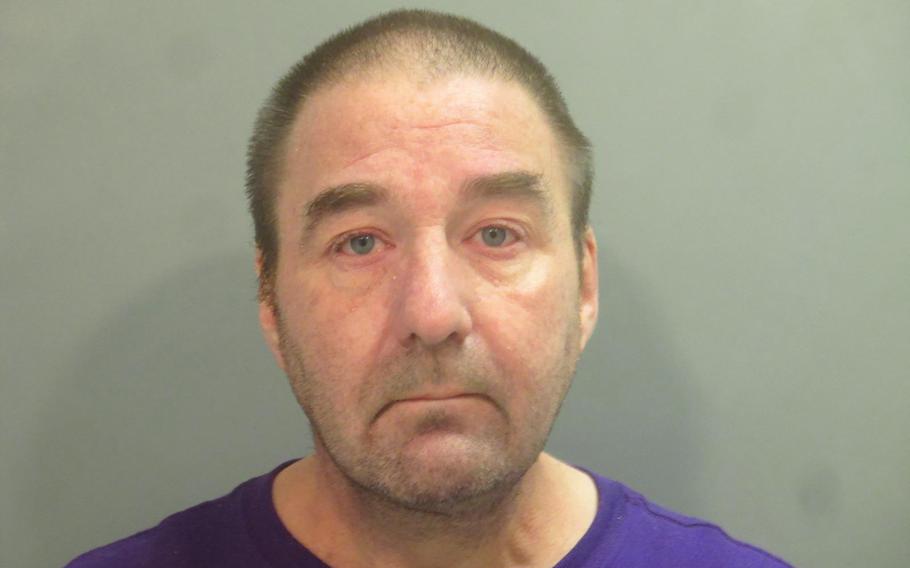

Robert Levy was arrested in August 2019 in Washington County, Ark. (Washington County Sheriff’s Office)

Levy, 54, who rose from temporary contract pathologist to chief of pathology during a 13-year tenure until his firing in 2018, was sentenced in January to 20 years in federal prison for involuntary manslaughter and mail fraud, following a plea agreement with prosecutors. He pleaded guilty last year to diagnosing lymphoma in an Air Force veteran who actually had a small-cell carcinoma. Levy admitted to falsifying the patient's medical record to state that a second pathologist agreed with his diagnosis; the patient later died. Levy also admitted to scheming to cover up his substance abuse problem.

When a team of outside pathologists reviewed almost 34,000 cases Levy had diagnosed since his hiring, they found that more than 3,000 had errors, 589 of them major mistakes that caused medical harm to veterans. At least 15 died.

In 34 of the most serious cases, VA called the patients or their surviving family members to tell them what happened. It's unclear from the report whether any of the other patients with serious misdiagnoses were formally notified.

The Washington Post reported many of Levy's misdiagnoses in 2019.

The Arkansas report comes three weeks after the release of another blistering investigation by Missal's office of oversight failures at a VA hospital in West Virginia. That report found cascading mistakes in quality control and patient care at the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center in Clarksburg that failed to stop a former nursing aide from injecting lethal doses of insulin into frail, elderly veterans in her care.

In Reta Mays’ case, her actions went undiscovered for almost a year. After confessing to her crimes, Mays was sentenced in May to seven consecutive life terms and an additional 20 years in federal prison.

Worley's attorney, Shane Wilkinson, said that Worley had cooperated with federal investigators and that "after a thorough investigation, it was very apparent Dr. Worley did a thorough job, but within the constraints of the Federal employment rules and regulations."

"It is my understanding that there have been recommended changes to certain policies that would allow supervisors more leeway in the future," Wilkinson said. "Dr. Levy's actions were tragic with tragic results. ... I understand that a report was probably necessary, but it is also easier to play armchair quarterback a few years later when all the facts and circumstances are known."

Following the failures in Fayetteville, VA agreed to make multiple agencywide changes on the inspector general's recommendations, including better competency assessments for newly hired and temporary medical staff, stricter protocols for pathologists, broad alcohol testing and better management of staff with drug or alcohol issues. Missal's office also recommended administrative actions for agency leaders involved in the Levy case.

The long-awaited investigation — on hold as the criminal case against Levy unfolded — brings more closure to a rare criminal case against a government physician. It also underscored a common failure by the agency to hold its medical staff accountable for administrative misconduct, audits and interviews show.

The case demonstrated the staffing challenges VA faces in rural communities, where it is often hard to recruit qualified specialists. When he arrived in Fayetteville in 2005, Levy was a star hire, an Air Force veteran with degrees from top medical programs.

But he also had jumped from job to job and acknowledged a previous arrest and conviction for drunken driving, warnings in his background that investigators said should have guided the hospital staff when troubled started.

Levy's eventual firing after an arrest for driving under the influence followed a tumultuous tenure during which colleagues in the pathology lab complained of witnessing his erratic behavior on the job. On multiple occasions, their complaints were not fully investigated — and Levy continued to read pathology slides while impaired, the report found.

In 2014, Worley told investigators that he heard "episodic, informal reports related to Dr. Levy's smelling like alcohol or other possible signs of impairment." But the chief of staff concluded that the complaints were "not actionable," according to the report.

On one occasion, Worley evaluated Levy after receiving a complaint that he smelled of alcohol. The pathologist "gave an implausible excuse for his smelling like alcohol (drinking a lot of juice)," according to the report. Worley concluded that Levy did not smell of alcohol, and did not take further action, the report said.

During one incident on duty in 2015, Levy smelled of mouthwash, had red glassy eyes and exhibited hand tremors, the report found. He agreed to alcohol testing. But Worley did not have him tested, concluding that VA policy prohibited drug testing of its medical staff. But in this case, the conclusion was incorrect: There is no prohibition when an employee agrees to take a test. The episode represented another missed opportunity to stop Levy, investigators said.

The hospital allowed Levy to enter a program for impaired physicians after another incident in 2016. A VA team did a limited review of his cases while he was in treatment, finding some misdiagnoses. But nothing further was done, the report said.

The eventual look at the full 12 years of his work in Fayetteville would find a consistent clinical error rate that hovered at 10% of his diagnoses — more than 10 times the normal misdiagnosis rate of 0.7% for pathologists.

At the time, the hospital also was learning that Levy was using his role as chief pathologist to subvert quality control in the lab. As a safeguard against errors, Levy and his deputy were required each month to review a random sample of 10% of each other's cases, a routine practice among pathologists.

The results of these "second reads" were communicated by sticky notes, a system of informal documentation that allowed Levy's misconduct to fester. It turned out that he was altering his deputy's reviews to show them as concurring with all of Levy's diagnoses, according to the report.

Levy consistently had a tiny official error rate, at times even zero. No one with the power to dig deeper noticed.

The peer review system was further flawed, investigators found, because the randomness of the samples allowed misdiagnoses to go undetected. The sample should have targeted cases with a higher risk of interpretation error — or ones that could result in clinically significant consequences.

Levy and his deputy did not get along, presenting another problem: A third pathologist should always join peer reviews to examine discrepancies in opinion on diagnoses in such a small practice, the report said. Otherwise, as the mounting problems in Fayetteville showed, there are no guardrails on the physician in charge.

"Dr. Levy developed quality management policies and controlled all aspects of the quality management program in a service with only one other pathologist (a subordinate of Dr. Levy), which made the process susceptible to subversion," the report concluded.

When investigators interviewed Levy's colleagues, they said they had been terrified to report more of what they witnessed, the report found.

"The OIG concluded that facility leaders did not meet [the Veterans Health Administration's] goal to establish an environment in which staff act with integrity to achieve accountability," it said.

To avoid detection of his severe substance abuse problem, Levy used his knowledge of toxicology and the science of blood testing and urinalysis to come up with a way to elude detection once he returned from rehab and agreed to regular drug and alcohol testing.

He acknowledged to prosecutors that he routinely took a substance called 2-methyl-2-butanol (known as 2M2B), which he bought online, to mask the alcohol level in his blood. The substance, which is not approved for individual use, cannot be detected in routine tests for drugs and alcohol.

When Levy came up for recredentialing every other year, the hospital did not ask other pathologists to review his work or assess his performance, instead turning to physicians without a background in his specialty, another failure investigators cited.

The case drew attention to what investigators, Congress and veterans groups have called a lax system of oversight of poor-performing VA physicians, who often are reassigned rather than dismissed.

Worley retired from the Fayetteville hospital in 2018 and now practices psychiatry at a local community clinic, his attorney said. He faced no formal consequences from VA for his role in the Levy case.

As the case first made headlines, Bryan Matthews, then-director of the Fayetteville hospital, was transferred to lead VA's Gulf Coast Veterans Health Care System in Biloxi, Miss., where he still works.