Mellisa Mendoza places white roses at a mural for Fort Hood Spc. Vanessa Guillen at a convenience store on July 6, 2020. (Jay Janner, The Austin American-Statesman/TNS)

AUSTIN, Texas — Latrece Johnson woke up gasping for air at exactly 2:43 a.m. March 14 in her home in Vidalia, Ga. She said it felt like a dream, but she knew instantly that something had happened to her son, Spc. Freddy Delacruz.

“I felt him take his last breath. I saw him call to me. I felt him being shot,” Johnson said, recalling the pain she felt at the exact time her son was shot six times in an apartment in Killeen, Texas. “I literally gargled on the same blood.”

Delacruz, 23, was shot and killed along with his pregnant girlfriend Asia Cline, 20, and Army veteran Shaquan Allred, 23. He was the second soldier murdered this year at Fort Hood but not the last.

Between March and June, the deaths of five soldiers have become suspected homicides, more than the past four years combined. At least two veterans who had separated from the Army at Fort Hood within the previous six months were slain. Additionally, two soldiers are alleged to have committed murder. In the previous four years, only two soldiers’ deaths were considered homicides, according to data from the Fort Hood Public Affairs Office. Both died in 2017.

In addition to the increase in homicides at Fort Hood, the number of violent crimes committed by soldiers at the post this year — and since 2015 — is alarming. The two issues raise questions: Why this post? Why now?

“The numbers are high here. They are the highest in most cases for sexual assault, harassment, murders, for our entire formation in the U.S. Army,” Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy said when he visited Fort Hood in early August.

Freddy Delacruz, right, is shown with his twin brother, Frederick, in this undated photo provided to Stars and Stripes. (Frederick Delacruz)

The Army Public Affairs office this week released the numbers McCarthy cited that day, which compare Fort Hood’s violent and nonviolent felony data from 2015 through 2019 to that of two installations of comparable size: Fort Bragg, N.C., and Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Wash.

Fort Hood averaged 129 violent felonies committed by soldiers per year. Fort Bragg had an average of 90, and Lewis McChord had 109. Violent felonies include crimes such as homicide, violent sex crimes, kidnapping, robbery and aggravated assault.

Fort Hood officials did not respond to questions concerning crime at the post.

A deadly 2020

All but two of this year’s homicides occurred within the city of Killeen, the town just outside the gates of Fort Hood. One other occurred in Harker Heights, a small suburb of Killeen. Those deaths received more public scrutiny after the international coverage of the disappearance and death of Spc. Vanessa Guillen.

The 20-year-old Houston native was bludgeoned to death in an arms room by Spc. Aaron Robinson, who with his girlfriend buried her body in a secluded area about 20 miles from the post. He shot himself dead when confronted by local law enforcement after her body was discovered June 30.

On March 1, Spc. Shelby Jones, 20, was shot and killed outside a strip club in Killeen. Though a redacted copy of the police investigation shows that 15 people were either involved in the incident or witness to it, a Bell County grand jury declined to indict the suspect June 10. The case has been “exceptionally cleared,” said Ofelia Miramontez, spokeswoman for the Killeen Police Department. This form of case clearance means elements beyond law enforcement’s control have prevented the agency from arresting and formally charging the offender. The district attorney did not say why the case was declined.

Spc. Shelby Tyler Jones, 20, was pronounced dead from a gunshot wound at 3:45 a.m. Sunday, March 1, 2020, outside of a convenience store on Fort Hood Street. (Facebook)

Two weeks later, Delacruz, Cline and Allred were killed.

On March 26, Michael Wardrobe, who separated from the Army in January, was shot and killed. Spc. Jovino Jamel Roy was arrested and charged with murder. A fight broke out between the 22-year-old men over an alleged love triangle involving Roy’s wife, the Killeen Daily Herald reported.

Guillen was killed on post the next month. During the two-month search for her, a tip led investigators to a field in Killeen on June 19, where police found skeletal remains of 23-year-old Pvt. Gregory Wedel-Morales. Homicide detectives are investigating that case, Miramontez said. Wedel-Morales went missing in August 2019, just days before he was set to begin out-processing from the Army. His unit labeled him a deserter, a status his mother had to fight to change so she could have her son returned home to Oklahoma and buried in a veterans’ cemetery.

Pvt. Gregory Wedel-Morales (Courtesy of Fort Hood Press Center)

On May 18, Pfc. Brandon Rosecrans, 27, was shot and killed in Harker Heights, a wealthier, quieter suburb just east of Killeen and Fort Hood. His body was found on the side of a residential road, and his vehicle was found on fire a few miles away. A civilian, Brandon Olivares, 28, was arrested and charged with Rosecrans’ murder in August. The two had a disagreement about the sale of a gun, and Olivares shot Rosecrans as he slept in his Jeep Renegade, according to court documents.

Pfc. Brandon Rosecrans (Courtesy of Fort Hood Press Center)

Calls for reform

Guillen’s death was horrific and shocking and has led to at least four separate ongoing Army investigations.

“We will do everything we can to protect her legacy by making enduring changes,” McCarthy said.

But when added to the four other violent deaths, there have been calls for major reforms from veterans, lawmakers and the families who have lost loved ones.

“It breaks your heart that the institution itself, or these bases, is just not getting a handle on this,” said retired Col. Ann Wright. Known for her opposition to the Iraq War, Wright has spent considerable time researching and speaking out against violence in the military.

She sees the current level of homicide at Fort Hood as “pretty consistent.”

“It takes some egregious thing that really comes to the public’s attention, like Vanessa’s murder, and then all of the sudden you start digging around a little bit more and find all these other things that have happened,” said Wright, whose research and outreach in the early 2000s focused on female soldiers who died in noncombat incidents on deployment. “I give credit to Vanessa’s family for really raising hell for long enough that they were able to get congressional attention on it, and then getting a firecracker lawyer. I’ve never seen anything happen quite like this. We were never able to get anything close to what Vanessa’s family has been able to do.”

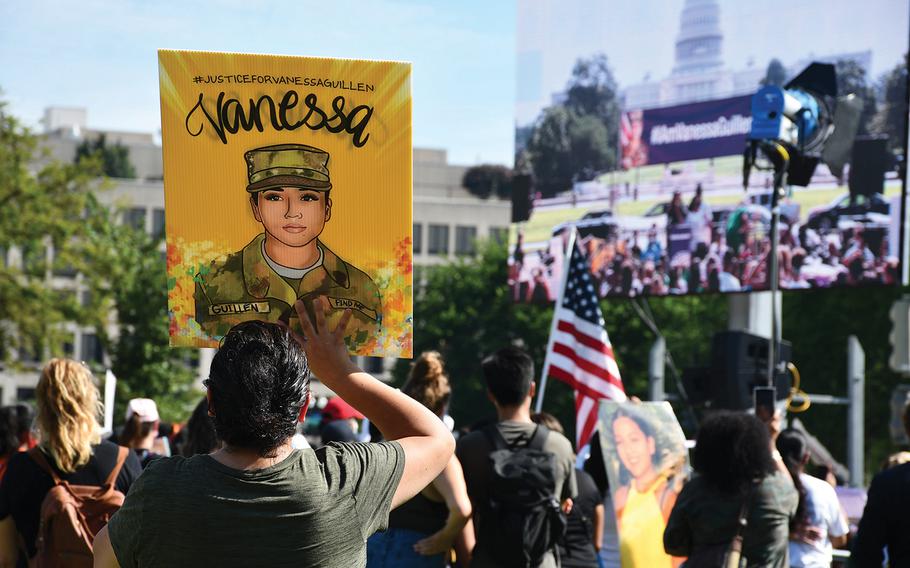

Activists held signs depicting Spc. Vanessa Guillen at a rally Thursday, July 30, 2020, in Washington, D.C. Guillen's family said Vanessa, who was murdered at Fort Hood in April, told them she was being sexually harassed but was too afraid to report it. (Nikki Wentling/Stars and Stripes)

The Guillen family spoke out about their disapproval of how the Army was handling search efforts. One month after Guillen’s disappearance, they began holding weekly rallies outside the gate of Fort Hood to keep the case in the spotlight. On June 15, they hired Natalie Khawam, that “firecracker” attorney from Tampa, Fla., who helped elevate their cause to Congress.

“I wanted to bring it to a national level because I knew we needed legislation,” Khawam said. “… It felt like it was more than Vanessa. It was not an isolated incident. It felt like it was widespread.”

Khawam, who said she represents hundreds of soldiers stationed around the world, said the Texas base gives her an uncomfortable feeling.

“It’s a ‘shut up and mind your own business’ mentality,’ Khawam said of leadership at Fort Hood. “It’s very totalitarian.”

She said she believes the problems at Fort Hood stem from toxic leadership. When speaking to people who have experienced or witnessed sexual harassment and assault, Khawam said the common refrain is that soldiers are told: “Just act like you didn’t see it.”

“Who’s teaching these people that?” she asked. “These are learned behaviors.”

Before Guillen went missing, she told her family she faced sexual harassment on base but was afraid to report it. While the family has said Robinson was harassing Guillen, Army investigators maintained they have not found any evidence to support that allegation.

The allegations have led to internal Army reviews of how the base and Guillen’s unit implement the Army’s sexual harassment and assault program, as well as an independent committee formed by McCarthy.

Made up of four veterans and a former FBI investigator, the committee will look at Fort Hood and the surrounding community to determine whether the command climate and culture “reflect the Army’s commitment to safety, respect, inclusiveness, diversity and freedom from sexual harassment.”

Its final report is due Oct. 30.

Keeping track

In the last five years, 165 soldiers assigned to Fort Hood have died, according to the Fort Hood Public Affairs Office, which regularly released information on soldiers’ death until a 2018 decision to stop the practice. The post was an outlier in this level of transparency.

In those years, seven soldiers died by homicide, while six died in a combat zone. The deaths of 70 soldiers were ruled suicides, and on- and off-base accidents resulted in the deaths of 60 soldiers.

Army and Defense Department officials did not respond to requests for similar information on deaths throughout the Army or other bases.

The annual Army Crime Report gives some insight into the level of criminal activity throughout the service. In fiscal year 2017 there were 56 homicide offenders and 72 homicide offenses. Of those offenses, 21 were charged as murder. In fiscal year 2018, 58 soldiers are listed as homicide offenders, and 17 of those soldiers were charged with murder.

()

The reports show that 5% of active-duty soldiers commit some form of crime. Of that, violent felonies make up only about 4% of all cases. Among the violent offenders, 90% of the soldiers come from ranks E1-E6. Those statistics were consistent in 2017 and 2018.

“We train people to be violent, but only, supposedly, on the orders of the government,” Wright said. “Tragically, the violent behavior flows into home life and sometimes to interactions with your own fellow service members.”

The post, the city

Fort Hood, with its 36,500 service members, and Killeen, population approaching 150,000, share a symbiotic relationship.

The post generated $29.8 billion for the Texas economy last year, according to the state comptroller. Fort Hood employs more than 12,000 civilians as Defense Department personnel, contractors and employees of its exchanges and commissaries.

Two of Fort Hood’s three gates that flow into Killeen deposit soldiers directly into an area of local businesses, barber shops and tattoo parlors. The third feeds onto a stretch of highway that recently expanded to a full-fledged interstate.

Bernie Beck gate at Fort Hood, Texas. (Rose Thayer/Stars and Stripes)

As Fort Hood has experienced an increase in homicides, so has Killeen. So far this year, the city has had 21 homicide victims, surpassing the 16 cases investigated in 2019, Miramontez said. That number includes Jones, Delacruz and Wedel-Morales. Police have closed eight of this year’s cases.

The two also share horrific histories of violence.

In 1991, a man drove his pickup truck into a Luby’s Cafeteria in Killeen and opened fire, killing 23 people and wounding 27. Fort Hood suffered a similar fate 18 years later when Maj. Nidal Hasan shot and killed 13 people and wounded 30 at the base’s Soldier Readiness Processing Center on Nov. 5, 2009.

For better or worse, the civilian community leaders outside of Fort Hood wholeheartedly support the base. Jean Shine, a local real estate agent who serves as a civilian aide to the Secretary of the Army, said in the wake of Guillen’s death, “everyone wants to help.”

The community is filled with retirees and former service members, many who chose to return to the area.

Shine said she finds the negative coverage of Fort Hood disappointing and unrepresentative of the community. She’s watched this year as her soldier-neighbors deployed — to work in combat zones, to quell civil unrest and to support America’s fight against the coronavirus pandemic.

“We put a lot on our military,” she said.

McCarthy met with Shine and other members of the community, as well as soldiers, in early August to get a better understanding what exactly is happening at Fort Hood.

“We are sitting down with a group of investigators to understand the root causes associated with the violence, felonies, violent acts, but better understand why this is happening at this installation,” McCarthy told reporters during the visit.

Killeen Police Department Chief Charles F. Kimble also met with McCarthy and described the relationship his department has with Fort Hood and the Army as “strong.”

Because the populations are so intertwined, he said the two are more like one community.

“Collectively, we know criminals do not concern themselves with city borders, let alone military installation borders, so from time to time, crime spills over from both ways,” Kimble said this week in emailed responses. The base and the police work collaboratively on cases when they can, he said.

Much of the violent crime in the city is caused by people engaging in “at-risk” behavior such as drugs and prostitution, Kimble said.

Asking for a solution

Air Force veteran Jennifer Norris believes Fort Hood’s current situation has been years in the making.

For the past decade, Norris, a trained social worker with a master’s degree in public policy, has been tracking crimes committed by and against service members and advocating for reform. She posts her research on her website, Military Justice for All.

She first focused her research on several large military bases, but after noticing a trend of Fort Hood deaths, Norris narrowed her efforts to the Texas post.

“I didn’t set up to go after Fort Hood at all. It’s a compilation of systematic issues,” she said.

At the end of 2017, Norris used her own money to travel from her home in Maine to Washington to meet with lawmakers. By the time she got home, Norris said she thought everyone had moved on without intending to address the problems.

“The other bases are nothing like Fort Hood is right now,” she said. “I think the anomaly with Fort Hood is that its isolated and that it’s such an economic powerhouse in the community that it’s in everybody’s best interest to protect it so they can protect themselves.”

Epilogue

Back in Georgia, Freddy Delacruz’s mother said she tries to remember the laughter and the joy he brought to her life. He was “her goofiness,” she said. The two spoke almost daily and there’s no denying the void that his death left in her days.

There’s also uncertainty because the case remains open. Johnson has business related to her son to deal with in Killeen, but with his killer still not arrested, she said she’s too afraid to travel there.

Delacruz’s family has been told that a suspect was identified, but it is now up to the Bell County District Attorney to determine whether charges will go forward. Killeen Police did not provide any updates to the case.

When asked about delays in arresting suspects, Police Chief Kimble said, ‘To secure an arrest warrant for a murder suspect, we must confer with the Bell County District Attorney’s office, who issue the complaint.” Waiting for lab results and evidence processing can delay when police approach that office.

“My mom is trying to keep calm and wait for the detective and stuff to call her,” said Fredrick Delacruz, Freddy’s twin brother and a soldier at Fort Campbell, Ky. “I’m uneasy. It’s taking too long for me.”

Johnson had pushed her twins to join the Army. They were restless at home and wanted to travel. They also struggled to find work, Fredrick remembered.

“I was happy and sad at the same time,” Johnson said. “I am proud of their service. I have always been proud of them. Always.”

Now, she worries about Fredrick. Even though he’s states away from Fort Hood, Johnson said she questions the safety of living around any Army post.

“It most definitely gives me concern of why. Why is it happening or what is going on where they’re not paying attention to soldiers missing or getting murdered?” Johnson said. “When they’re in the Army, that’s [supposed to be] the safest place. Fort Hood just taught me otherwise.”