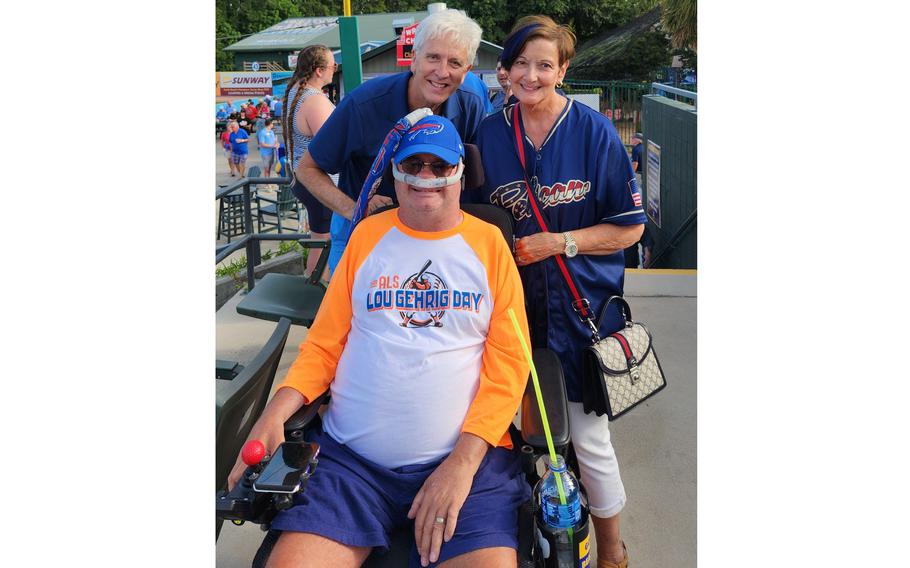

Veteran Tim Ritter, who uses ventilator to breathe, attends Lou Gehrig Day for the Myrtle Beach Pelicans baseball team. Standing behind him is his wife, Marie Amero, a Navy veteran who served for 31 years, and Steven Wetzel, a VA respiratory therapist who also is a Navy veteran. (Tim Ritter)

WASHINGTON — Advocates for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis — a fatal condition known as Lou Gehrig’s disease — urged lawmakers to keep funding the National ALS Registry that serves as a centralized database with patient information on the terminal disease that afflicts veterans at a higher rate than the general population.

More than a dozen nonprofit agencies that assist ALS patients and support research sent a letter this week to the 43 members of the ALS Congressional Caucus, a bipartisan group of House and Senate lawmakers, after a leaked proposed budget memo from the Health and Human Services Department called for defunding the registry and a biorepository with thousands of lab specimens.

The April 10 memo also proposes defunding the Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program and the Climate and Health Program. All three are part of the National Center for Environmental Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Established by Congress, the National ALS Registry includes demographic, military, job history and medical information on more than 20,000 people with the disease that attacks cells in the brain and spinal cord. People with ALS experience progressive muscle weakness and paralysis until they no longer can eat, move, talk or breathe on their own. The disease has no known cure.

“With $10 million in funding, the CDC’s National ALS Registry and biorepository represent a tiny fraction of the federal budget. Yet they deliver outsized impact, especially for our veterans, who are disproportionately affected by this devastating disease,” said Melanie Lendnal, attorney and a senior vice president at the ALS Association, a nonprofit that supports ALS research and advocates for people with ALS.

Elimination of the registry funds would dismantle a scientific and public health resource that thousands of patients have contributed to for 17 years, according to the letter, signed by the ALS Association, Les Turner ALS Foundation and ALS United, among other groups.

“We call on you, as members of the ALS Caucus, to take immediate and decisive action to restore and protect funding for the National ALS Registry and Biorepository,” the letter reads.

Tim Ritter, an Army and Navy veteran with ALS, has participated in numerous surveys for data collection in the registry. Ritter said he shared his medical and personal history for inclusion in the database after his ALS diagnosis in 2015 at the age of 50.

“ALS is like a train that comes barreling through your house. It will reach out and disrupt everything,” said Ritter, who uses a ventilator to breathe. “It will turn your life upside down and the lives of those closest to you.”

Ritter has been using a motorized wheelchair since losing the use of his arms and legs eight years ago.

“I cannot perform any of the functions of daily living. I require round-the-clock care,” said Ritter, who relies on his wife as primary caregiver. “When I was no longer ambulatory, I had to move into a wheelchair.”

Tim Ritter stands in a Navy patrol boat in 2010 as it patrolled the northern Arabian Gulf. (Tim Ritter)

But Lendnal said the registry information is offering a measure of hope for people with ALS and bringing scientists closer to identifying potential environmental factors that might trigger the disease. The National ALS Registry is the primary nationwide initiative for collecting and analyzing data supplied by people with ALS, Lendnal said. Individuals respond to a series of surveys that follow the progression of the disease.

“Researchers have theorized the higher risk of ALS among military service members could be caused by exposure to toxic substances or head injuries. However, more research is needed to figure out exactly what aspects of military service increase ALS risk. This is a question registry data can help answer,” she said.

Ritter, 60, of South Carolina is among the 10% of patients who have survived 10 years or longer with ALS, which has an average life expectancy after diagnosis of three to five years. Ritter was medically retired in 2016, after 25 years of service.

In 2008, the Department of Veterans Affairs established ALS as a presumptive condition for veterans with the disease to receive health care coverage and other benefits. Presumptive coverage means the VA will automatically consider ALS to be service connected regardless of when the condition is diagnosed or how long after service it developed.

Ritter gets his health care and therapy at the Charleston VA Medical Center, where he participates in a multi-disciplinary clinic that includes a team of specialists. He sees a neurologist, dietician, occupational therapist, physical therapist and a nurse practitioner on a regular basis.

Congress directed the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Research Program in fiscal 2025 to prioritize clinical research, including early-phase clinical trials, toward finding effective treatments for service members, veterans, their families and the public, according to Ripple Effect Communications, which provides services to the Army and other government agencies.

Ritter said he was working as a physics professor at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md., in 2015, when he first noticed changes in muscle control when he was teaching classes. He was having trouble picking up and grasping chalk.

He was diagnosed at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md.

“I still remember very clearly hearing the words, ‘You have been diagnosed with ALS,’ ‘‘ he wrote in a blog post for the ALS Association.

ALS first became widely known after the New York Yankees baseball star Lou Gehrig was diagnosed with the illness in 1939 at the age of 36. The disease brought an abrupt end to Gehrig’s 17-year baseball career.

Ritter joined the Army in 1982 after high school and spent two years on active duty. He transferred to the Army Reserve and was honorably discharged in 1989 as a staff sergeant.

In 1998, Ritter joined the Navy Reserve. He was mobilized after the 9/11 terrorist attacks and worked in the Naval Criminal Investigative Services. He deployed to Iraq from 2009 to 2010.

“I was diagnosed in March 2015 and stopped teaching in spring 2016,” he said. “If I really had wanted to, I could have continued working. But I was getting weak. I did not know how fast my disease would progress.”

Ritter said there continues to be a lack of knowledge in the public about the disease itself.

“Many people have heard about the disease, but few people understand the details of the illness,” he said. “I’ve been fighting this for 10 years. I am not a senior military officer or a university professor anymore. But while I still have a voice, I consider it my responsibility to speak out for those who can’t about the vital importance of this registry and of finding a treatment and cure for this awful disease.”