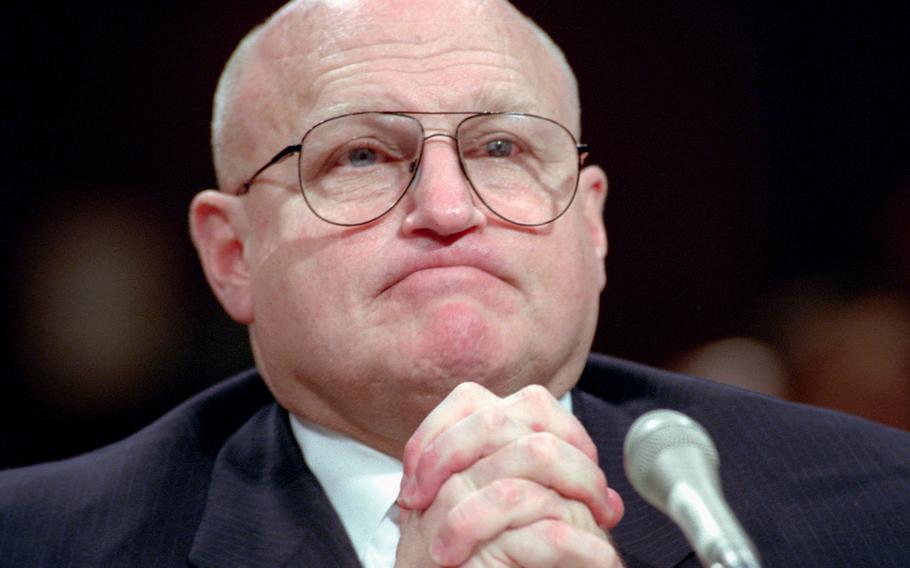

Then-Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage in 2003. (Ray Lustig/The Washington Post)

Richard Armitage, who as deputy to Secretary of State Colin Powell helped guide U.S. foreign policy during President George W. Bush’s tumultuous first term and was a central figure in chapters of American national security from the Vietnam War era to the post-Sept. 11, 2001, war on terror, died April 13 at a hospital in Arlington, Virginia. He was 79.

The cause was a pulmonary embolism, said his wife, Laura.

Barrel-chested and with a vocabulary often closer to a sailor’s than a diplomat’s, Mr. Armitage was little known to the wider public until 2006 — more than a year after he retired as deputy secretary of state — when he publicly admitted his role three years earlier in events that led to the unmasking of a serving CIA officer, Valerie Plame.

Mr. Armitage apologized for what he said was his inadvertent role in the “Plame affair,” which was widely seen as an attempt by high-ranking White House officials in the Bush Administration to punish Plame’s husband, retired ambassador Joseph C. Wilson, for publicly contradicting a key piece of the White House’s rationale for the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq.

Wilson, who had undertaken a fact-finding mission for the CIA, said there was no evidence Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was pursuing a nuclear weapons program — undercutting one of Bush’s key messages during his 2003 State of the Union address.

Mr. Armitage said his disclosure to a columnist that Wilson’s wife worked for the CIA was made in error and that he had not realized she was working undercover. He apologized publicly, cooperated with a federal investigation and was not charged with wrongdoing. Without cover, Plame was forced to retire from the spy agency.

After leaving government service in 2005, Mr. Armitage ran his own consulting firm and traveled frequently to East Asia, where he maintained contacts with the highest echelons of governments in Japan, South Korea and other countries allied to Washington.

It was in Asia where Mr. Armitage began his career after graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1967. He served three combat tours, including as an adviser to South Vietnam’s riverine forces.

He left military service in 1973, but the Pentagon asked him to return to Vietnam in early 1975 to report on the deteriorating situation for the U.S. military and the U.S.-backed South Vietnamese government. He was soon asked to organize a mission to deny communist North Vietnam the use of American military machinery, including ships and planes, by destroying it if necessary.

Mr. Armitage, who had little patience for bureaucratic niceties, developed his own ideas about how to proceed, especially after coming under air attack at Saigon’s airport. Working with a South Vietnamese navy captain, he hatched a plan to evacuate South Vietnam’s navy, along with sailors and their families, rather than destroy the vessels.

As many as 31 ships, and between 28,000 and 30,000 people, sailed to the U.S. naval base at Subic Bay in the Philippines, Mr. Armitage said in a 2018 oral history. He and his South Vietnamese partner acted without explicit authority from the governments either in Washington and Saigon.

“My government was quite angry,” Mr. Armitage said. “It was my plan. It wasn’t their plan.”

During Republican presidential administrations in the 1980s and early 1990s, Mr. Armitage served in senior defense and diplomatic posts. In 2001, he and Powell, a retired Army general who had been the first Black chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, took the helm at the State Department after Bush’s election victory.

While it was Powell who was the secretary of state and Cabinet member, the two men, both Vietnam veterans who had bonded during Ronald Reagan’s first term, ran Foggy Bottom more as pilot and wingman than as principal and deputy. When Powell died in 2021, Mr. Armitage was the first guest speaker at his funeral.

Mr. Armitage had joked in his confirmation hearing to be deputy secretary of state that the art of diplomacy involved saying, “Nice doggy, nice doggy, until you can find a big stick.”

As State’s No. 2, he often acted as a troubleshooter in tense situations that required blunt talk. He helped negotiate the release of 24 American airmen whose U.S. Navy electronic spy plane collided with a Chinese fighter jet in April 2001 and was forced to land on China’s Hainan island.

After the September 2001 al-Qaeda terrorist attacks on the United States, Mr. Armitage flew to Pakistan — which the United States knew to be covertly supporting Islamist militants — and presented an ultimatum: Islamabad had to decide whether it was “with us or against us” in the coming fight against al-Qaeda, the Taliban and other violent extremists.

He denied telling Pakistani officials they risked being bombed “back into the Stone Age” if they did not cooperate, as Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf later claimed.

“It would be completely out of character for me to threaten the use of military force when I was not authorized to do so,” Mr. Armitage told NPR in 2006. “I don’t command aircraft and could not make good on such a threat.”

In 2002, as the Bush White House stepped up its efforts to make the case for invading Iraq, often deploying cherry-picked or misleading examples of Hussein’s ties to terrorism and his supposed nuclear, biological and chemical weapons programs, Powell and Mr. Armitage increasingly found themselves outside the inner circle of policymaking, eclipsed by hawks such as Vice President Dick Cheney and Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld.

Neither Powell nor Mr. Armitage argued directly against invading Iraq. But both men counseled the White House that the United States should assemble a large international coalition behind its efforts and plan carefully for what was likely to be a messy aftermath following Hussein’s ouster.

It was the debate over Iraq’s weapons programs, and Mr. Armitage’s penchant for trading gossip, that tripped him up in what arguably was the biggest mistake of his government career.

In his January 2003 State of the Union address, Bush had cited a British intelligence finding that Hussein had been seeking significant quantities of uranium in Africa for his presumed nuclear weapons program. Bush made his statement despite deep doubts at the CIA and State Department about the intelligence. The country at issue was Niger, which had a significant uranium mining industry.

In July 2003, Wilson revealed in a New York Times op-ed that he had traveled to Niger in February 2002 at the request of the CIA to investigate the purported British intelligence findings. His piece, titled “What I Didn’t Find in Africa,” largely debunked the Iraq-Niger claims.

Eight days later, columnist Robert Novak wrote that Wilson’s wife was Plame, a CIA officer who specialized in weapons of mass destruction programs.

Mr. Armitage was one of the sources for Novak’s report, and separately had shared information about Wilson’s wife’s employer with Washington Post editor Bob Woodward.

In a 2006 interview with McClatchy Newspapers, Mr. Armitage expressed regret for his actions and said he contacted the Justice Department in October 2003 as soon as he realized he was a source for Novak’s column.

“There wasn’t a day that went by that I didn’t feel that I let down the president, the secretary of state, the Department of State, my family and friends and for that matter, the Wilsons,” he said. He added that he did not know Wilson’s wife by the name Valerie Plame or that she was working undercover.

Mr. Armitage said he delayed making public his role at the request of the federal prosecutor in the case, Patrick Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald’s probe led to the conviction of Cheney’s chief of staff, I. Lewis Libby Jr., for lying during the investigation. Bush commuted Libby’s 30-month prison sentence and, in 2018, President Donald Trump pardoned him.

Richard Lee Armitage, the son of a businessman and a nurse, was born in Wellesley, Massachusetts, on April 26, 1945, and grew up in Atlanta, where he graduated from St. Pius X Catholic High School in 1963.

In 1968, he married Laura Samford. In addition to his wife of Pooler, Georgia, survivors include eight children; a brother; a sister; and 12 grandchildren. He and his wife also served as foster parents for dozens of children.

Throughout his career, Mr. Armitage made it a point to spot and nurture promising young military and diplomatic officers, in the process building a network of confidants in government long after he had left.

“His example shaped and inspired generations of public servants. I was deeply fortunate to be one of them, and equally fortunate to be his friend,” said William J. Burns, the former CIA director who worked for Mr. Armitage and Powell at the State Department.

Mr. Armitage was a lifelong Republican, but his belief in a robust American role in the world and the importance of global alliances left him and many of his generation on the periphery in a political party that, in the Trump years, became increasingly nationalistic and isolationist. In the 2016 presidential campaign, he endorsed Democrat Hillary Clinton over Trump.