Army Secretary Daniel Driscoll stands by a new sign for Fort Bragg on Friday, March 7, 2025, during an official ceremony at the North Carolina Army post marking the return of the name Fort Bragg. The base was renamed Fort Liberty in 2023. (Corey Dickstein/Stars and Stripes)

FORT BRAGG, N.C. — Army Pfc. Roland L. Bragg’s youngest daughter shrugged off the idea that there was anything cynical about choosing her father as the new namesake for the service’s largest installation once named for a Confederate general.

“My father was a very humble man, and he was a good man, and he did what was right,” Bragg’s 69-year-old daughter, Diane Watts, said Friday at the North Carolina post where she and her family members gathered with Fort Bragg’s top brass to recognize its new — and old — name. “I couldn’t be more thrilled. They found a good one in my father’s name.”

Less than two years after the Army officially changed Fort Bragg — then named for Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg who was a slave owner and failed military tactician who struggled to relate to his own troops — to Fort Liberty in June 2023, the world’s most populous military base is again Fort Bragg. This time named for Roland Bragg, the little-known World War II private whose Battle of the Bulge heroics earned him a Silver Star and a Purple Heart.

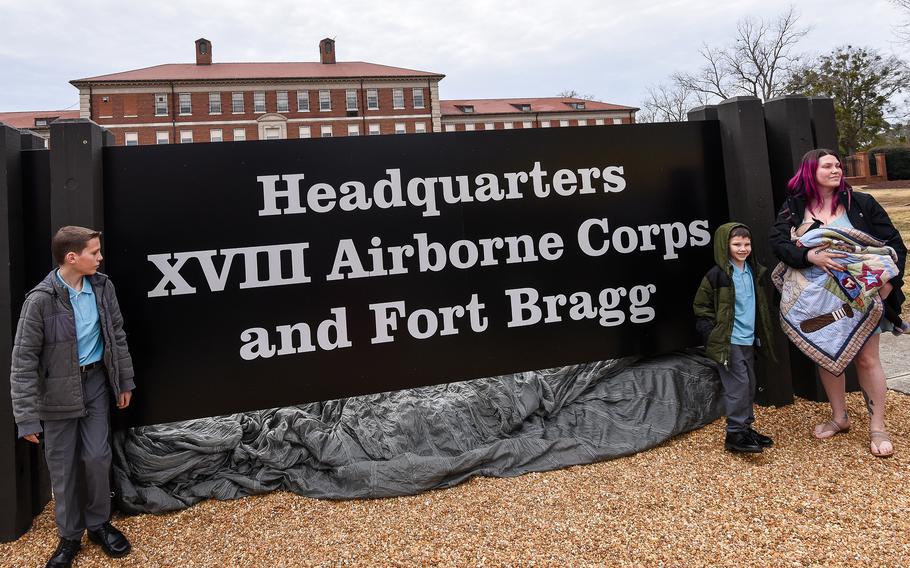

Family members of the late Pfc. Roland L. Bragg pose by a new sign on the North Carolina Army post now named for him during a ceremony Friday, March 7, 2025. The Army renamed the installation after the World War II Silver Star recipient last month, after it had spent almost two years as Fort Liberty, a name chosen by a committee tasked with stripping the Army of Confederate ties. Fort Bragg was originally named for Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg. (Corey Dickstein/Stars and Stripes)

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth ordered the change last month, undoing a yearslong and multimillion-dollar effort to find a new name for the post and eight other Army installations associated with the Confederacy. Hegseth had blasted the name changing efforts as “woke” and damaging to the military’s intergenerational bonds before taking the Pentagon’s top job under President Donald Trump, who has also long opposed the installations’ name changes.

Hegseth did not consult with Pfc. Bragg’s family before delivering the order to revert the post to Fort Bragg in his honor. Watts said she only learned of the name change honoring her father when a news reporter called her shortly after the announcement. She thought it was a “prank call,” she said.

On Friday, just outside the 18th Airborne Corps’ headquarters on Fort Bragg, Lt. Gen. Gregory Anderson, the unit’s commander, joined Col. Chad Mixon, the post’s garrison commander, in permanently retiring the short-lived Fort Liberty colors and replacing them with the once-retired Fort Bragg flag.

Officials made no mention of the post’s past ties to the Confederacy during the ceremony. Anderson said they were choosing to look forward with Pfc. Bragg as a perfect example of an “ordinary hero” forged on Fort Bragg’s vast training ranges.

“Over 80 years have passed since Roland Bragg arrived here, eight decades of soldiers from Fort Bragg deploying to every major conflict, defending America and her allies across the globe,” the lieutenant general said. “Today, we salute a man who answered the call from North Carolina and forged the best version of himself, and so today, we honor a hero worthy of the name Bragg, which is synonymous with excellence.”

The 172,000-acre Fort Bragg is the most populous military base in the world, boasting some 282,000 people, including 50,000 active-duty service members.

Known throughout the Army as “the center of the universe,” the base hosts some of the Army’s most-deployed units, including its immediate response force — an 82nd Airborne Division unit tasked with always being prepared to deploy quickly. The installation is also home to key units such as the 18th Airborne Corps, Army Forces Command, Army Special Operations Command, 1st Special Forces Command, 3rd Special Forces Group, Army Reserve Command, the Army’s most elite unit known as Delta Force and the multiservice Joint Special Operations Command.

Officials have said the installation boasts the second-largest population of general officers in the world after the Pentagon.

Bragg’s Army service was brief but action-packed, and family members said it left a profound impact on him even though he rarely talked about his military days.

Bragg of Webster, Maine, was drafted into the Army as a 20-year-old in 1943, according to the service. He trained at Fort Bragg before deploying to Europe to fight with the 513th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 17th Airborne Division in the 18th Airborne Corps.

In January 1945, amid the fierce fighting on the frozen battlefields of Bastogne, Belgium, Bragg was wounded and taken prison alongside four other soldiers by German troops. The captured soldiers were transferred to a German aid station where Bragg found he had something in common with their German guard — both were freemasons, Anderson said.

“They somehow convinced the German guard to let the prisoners go, but only if [Pfc.] Bragg first knocked the German guard out with a rifle, so it looked like he struggled,” the general said. “Wounded as he was, Pfc. Bragg was more than happy to oblige.”

Bragg took the German’s uniform, stole a nearby ambulance and loaded his fellow wounded Americans into the back and raced toward U.S. lines under heavy fire. He survived, but he believed for more than 50 years that none of the men in the back of the ambulance made it. Only decades later did he learn one of the men did survive, his family members said Friday.

Army Lt. Gen. Gregory Anderson escorts Diane Watts, the youngest daughter of Pfc. Roland L. Bragg, and her family members during a ceremony on Friday, March 7, 2025, to mark the return of the North Carolina Army post’s original name. After being known as Fort Liberty for almost two years, the post is again Fort Bragg, named now for the World War II Pfc. Bragg instead of Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg. (Corey Dickstein/Stars and Stripes)

By November 1945, Bragg left the Army to return to Maine where he spent his life running an auto repair and salvage garage and raising his three daughters. He died in 1999.

Watts said Friday that she knew little of her father’s military service until her mother grew very sick toward the end of her life. That’s when her father opened up to her about his World War II experiences, she said.

“It was the first time I really heard him talk about the war and all the atrocities that he had lived through and experienced,” Watts said.

In one instance, she said, Bragg had placed in his breast pocket a package with a set of steel pencils that her mother had sent him so he could write letters home. He almost did not pick up the package before going into battle that day, she said.

“And he went out and got shot that day, and if he hadn’t had that pencil set in his pocket, he would have been killed instantly, because the bullet would have gone straight through his heart,” Watts said her father told her.

Rebecca Amirpour, Bragg’s granddaughter, said he was a constant and steady presence in her life growing up in Maine. She described her granddad as a jokester who “didn’t take things to seriously.” But he was also a pillar of their small community.

Like other family members, she knew little of his military service.

“I never saw my granddad wear his military uniform,” she said Friday. “He was not one to go to a Memorial Day parade or a Veterans Day parade – even one Memorial Day when I was marching in the parade in our town, he was working. The uniform I knew him to wear was green and blue Dickies work clothes. … He was strong, hardworking and proud.”

Anderson said soldiers at Fort Bragg could now relate proudly to the post’s namesake.

“His story is similar to the stories we’re making,” the general said. “An ordinary person comes to Fort Bragg to serve his nation or her nation, and they do great things. That’s why today is such a special day for us.”

The installation’s naming reversal will come with a cost, but Bragg officials insisted Friday that they could do it much cheaper than in 2023 when Fort Bragg became Fort Liberty.

Army Col. Chad Mixon, left, and Lt. Gen. Gregory Anderson, right, unveil the Fort Bragg colors on Friday, March 7, 2025, during a ceremony to mark the return of the North Carolina Army post’s original name. After being known as Fort Liberty for almost two years, the post is again Fort Bragg, named now for World War II Pfc. Roland L. Bragg instead of Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg. (Corey Dickstein/Stars and Stripes)

Mixon, the garrison commander, said he believed the total cost to change the name back to Fort Bragg — including new signs and updated websites — would be less than $1 million.

“We’ve done this before,” he said. “You know, we did this a couple years ago, and we’ve got a lot of know how this time around.”

It was not immediately clear Friday how the Army would pay for the name flip-flop. Mixon said his office was keeping track of all the costs and would seek reimbursement from a higher authority “as we get to the end” of the process.

He expected that process to be fully completed on the post by May 31. Off the installation, road signs and some Fayetteville, N.C., businesses still bared the name Fort Liberty on Friday.

Anderson said he was not certain how people would remember the brief period in which Fort Bragg was known as Fort Liberty.

“I can’t say what people will think 15 years from now,” the general said. “But I will say that 15, 20 years from now, this place will still be producing warriors for our nation. That I can pretty much tell you with 100% confidence.”