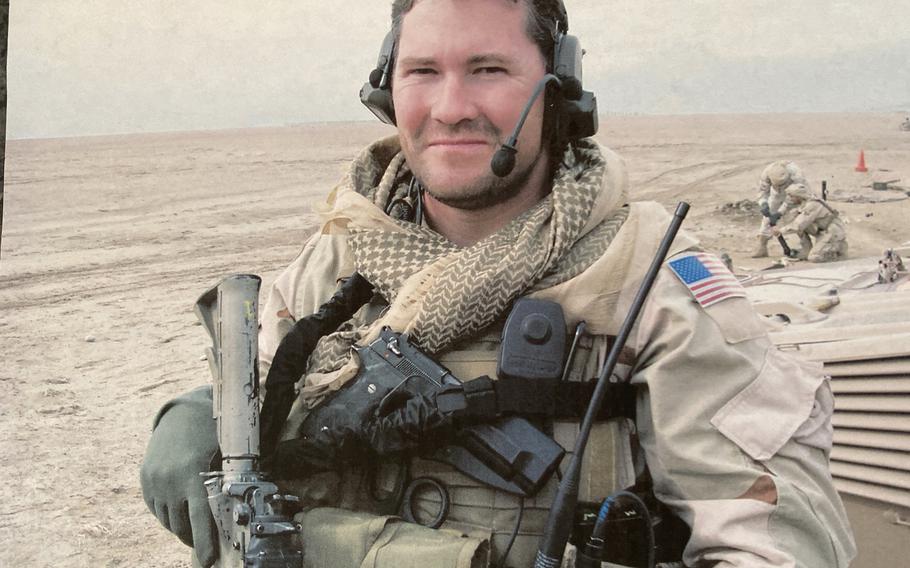

Michael Waltz, President-elect Donald Trump's choice for national security adviser, during a deployment as a Green Beret to Afghanistan’s Tagab Valley in 2006. He was an officer in the National Guard who served in Afghanistan with the 20th Special Forces Group. (Michael Waltz via The Washington Post)

In February 2020, Rep. Michael Waltz, then a first-term GOP lawmaker, received a coveted invitation to fly to his home state of Florida aboard Air Force One. During the flight, he seized the opportunity to lobby President Donald Trump about an issue to which he had devoted most of his career: the war in Afghanistan.

Trump had just approved a conditional peace agreement with the Taliban that called for the full withdrawal of U.S. troops within 14 months. Waltz, a Green Beret who had served two combat tours in Afghanistan, pleaded with the president to reconsider, arguing that the Taliban couldn’t be trusted and that the U.S. military needed to stay indefinitely. Yet Trump, who had campaigned on a promise to end the war, was unmoved. “We’ve been there so long,” he told Waltz, according to the congressman’s recently published memoirs. “It’s time.”

Despite their fundamental disagreement over the longest war in American history, Trump has tapped Waltz to return with him to the White House as national security adviser. The job does not require Senate confirmation but is one of the most powerful posts in Washington. In an administration that Trump is stacking with figures who share his isolationist leanings, Waltz stands out as the opposite: a post 9/11 veteran who still favors long-term commitments of U.S. troops to fight al-Qaeda, Islamic State and other terrorist groups overseas.

Waltz’s views are a reminder that sharp differences exist within Trump’s inner circle about how his “America first” campaign rhetoric should apply to myriad national-security challenges that his administration will inherit when it takes power next week.

In a recent interview with The Washington Post, Waltz, 50, downplayed his differences with Trump over Afghanistan and pledged to faithfully execute the boss’s wishes, pointedly drawing a contrast with aides who tried to obstruct Trump’s foreign policy decisions during his first term. “He welcomes disagreement. He welcomes the vigorous debate. But when he makes the decision, he expects you to implement it, and I will do that,” Waltz said.

At the same time, Waltz has made clear that his National Security Council staff at the White House — including career government employees — must be loyal to Trump. Last week, he told Breitbart News that he would ensure all staffers “are 100 percent aligned with the president’s agenda.”

Brian Hughes, a spokesman for Trump’s transition team, described Waltz’s difference of opinion with Trump over the 2020 deal with the Taliban as “not a disagreement but a discussion. Rep. Waltz clearly agreed with President Trump that there had to be a political solution in Afghanistan.”

In an email, Hughes noted that Trump decided at the end of his first term to leave a small military presence at Bagram air base in Afghanistan “to ensure the Taliban would honor their agreement.” Hughes blamed the Biden administration for bungling the final withdrawal.

When he moves into his West Wing office on Monday, Waltz will be responsible for coordinating U.S. policy on the world’s most pressing flash points, including relations with China, Russia, Ukraine and Iran. But he — and Trump — will also have to confront lingering fallout from Afghanistan and who should be held responsible for the war’s many failures.

Waltz and Rep. Bob Good (R-Virginia) arrive for a House Republican Conference on Oct. 13, 2023, in Washington, D.C. (Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post)

After Trump’s term ended, President Joe Biden upheld his accord with the Taliban and ordered the remaining 2,500 U.S. troops in Afghanistan to leave by September 2021. That culminated in the sudden collapse of the Afghan government, the emergency evacuation of the U.S. Embassy in Kabul and the frenzied exodus of thousands of Afghans who helped the United States during the war. Thirteen U.S. troops were killed in an attack during the final week of the withdrawal.

During last year’s presidential campaign, Trump promised to fire generals and diplomats who oversaw the 2021 pullout, excoriating them — and Biden — for the disastrous retreat. “We’ll get the resignations of every single senior official who touched the Afghanistan calamity to be on my desk at noon on Inauguration Day,” he told a National Guard conference in August.

Waltz also has criticized the Biden administration for botching the U.S. exit from Afghanistan. But unlike Trump, he has said it was a mistake for U.S. troops to leave and that they should have stayed for decades, if necessary, to deter jihadists and to maintain control over Bagram, a strategic air base near China’s western border.

In interviews, televised appearances and his writings, Waltz has repeatedly warned that terrorists are regrouping in Afghanistan and will try to attack America again as they did on 9/11. He has suggested the Pentagon may have to send forces back to Afghanistan eventually, just as it did to Iraq to fight the Islamic State three years after pulling out of that country in 2011.

“If we don’t fight the war on terrorism in places like Kandahar, that war will come to places like Kansas City,” Waltz wrote in “Hard Truths: Think and Lead Like a Green Beret,” a memoir that he published in October. “That’s not hyperbole — it is historical fact.”

In his interview with The Post, Waltz declined to specify how U.S. policy toward Afghanistan might change under Trump or to elaborate on scenarios under which U.S. forces could return there. But he emphasized that the United States needed to improve its ability to collect intelligence from inside the country.

The Trump administration will “be taking a hard look at the intelligence community and the counterterrorism enterprise, and what kind of eyes and ears do we have, to make sure we’re not surprised again — yet again — from that part of the world,” Waltz said. “I wouldn’t interpret that as, ‘We’ve got to go back and fight in Kandahar.’ I would interpret it as, ‘I don’t want to wait until a Kansas City is hit.’”

Ever since Waltz rejoined the U.S. Army in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, the war in Afghanistan has shaped his entire career in the military, politics, media and business. His extensive experience in the field left him more hawkish on Afghanistan than Trump, who soured on the war more than a decade ago and once called the prolonged conflict “a complete waste.”

Colleagues and friends say the lessons Waltz drew from Afghanistan have influenced his worldview and given him credibility with Trump, even if he and the president-elect have disagreed on the war.

“If you look at the breadth and depth of his experience, this guy has done it all, from the street level to the pinnacle of national security and his time in Congress,” said Ryan McCarthy, who served as Secretary of the Army during Trump’s presidency and has known Waltz since the 1990s, when they attended Virginia Military Institute, or VMI. “National security runs through his veins. It’s his passion, his life.”

Michael Vickers, a former senior U.S. intelligence official and Green Beret who worked with Waltz during the Bush and Obama administrations, said his main challenge as national security adviser would be to serve as “an honest broker” in the decision-making process at the White House and as a conduit between Trump and senior members of his Cabinet. He said Waltz was well-qualified for the role.

“The key thing is really the relationship with the president,” said Vickers, who also served as an independent director for a defense-contracting firm that Waltz co-founded. “It’s a pretty high-level political job as well as a national security job.”

A native Floridian, Waltz grew up in Jacksonville, raised by a single mother. In 1992, he moved to Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains to attend VMI, a state-supported military college known for its exacting academic, physical and disciplinary standards.

Of the 430 “rats” — VMI’s term for new cadets — who enrolled with him, fewer than half made it to graduation four years later, he said in an oral-history interview for the Library of Congress. “You get your head shaved every Monday. You get the crap beat out of you by the upperclassmen. And eventually, at the end, you’re recognized as a human being,” he added.

Waltz received an Army ROTC scholarship and majored in international relations. He studied abroad at the University of Valencia and became fluent in Spanish. He also boxed for the VMI club team.

One of his roommates, Jon Sherrod, said Waltz thrived on the challenges that the school threw at them. “Mike chose VMI because of its rigorous standards. At 18, he was more clear-eyed about that than I ever was,” Sherrod recalled.

Upon graduation, Waltz was commissioned into the Army and assigned to an armored cavalry unit. He graduated from the Army’s Ranger school, a notoriously grueling course, and was selected to join the Special Forces and become a Green Beret.

Michael Waltz as a Green Beret in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, in 2006. (Michael Waltz via The Washington Post)

In October 2000, Waltz left the Army to take a job as a management trainee with a diamond company. But a year later, after the 9/11 attacks, he rejoined the military as a part-time soldier in the Army National Guard, he said in his interview with The Post.

His introduction to Afghanistan came when he deployed with a Special Forces unit to Central Asia in 2003. From a base in neighboring Uzbekistan, he made brief trips into Afghanistan that didn’t involve combat, he told The Post.

When his call-up with the National Guard ended the following year, he landed a civilian staff job at the Pentagon in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, focusing on counternarcotics policy. Because Afghanistan produced most of the world’s opium, he wrote in his memoir, the country demanded much of his time.

In September 2005, his National Guard unit returned to Afghanistan for a year-long deployment. As a captain with the 20th Special Forces Group, Waltz led a team of Green Berets that served as a liaison to NATO forces and other allies in southern Afghanistan.

Conditions had deteriorated since his last call-up. In remote areas, U.S. troops began to find themselves outnumbered by the resurgent Taliban.

In May 2006, Waltz and five other U.S. Special Forces personnel were guiding about three dozen allied troops from the United Arab Emirates on a mission to Musa Qala, in northern Helmand Province, to scout a location for a new firebase, according to an account provided by Waltz in “Warrior Diplomat,” another book that he published in 2014.

An operations officer at command headquarters had warned Waltz not to go, saying the route was too risky because of an influx of Taliban fighters. But Waltz and the UAE forces, which were part of the U.S.-led military coalition in Afghanistan, resolved to press ahead anyway, he wrote.

After a few hours, their convoy of about eight vehicles ran into an ambush in the town of Sangin, where Taliban armed with mortars and rocket launchers pinned them down in a crossfire. The convoy became separated and struggled to fight its way out, Waltz wrote.

As Waltz’s armored Humvee hurtled along a dirt track, a Taliban sniper took aim at Gordon Cook, a Special Forces medic riding in the exposed rear of the vehicle. Cook was hit in the chest, right arm and left thigh, opening his femoral artery. In an interview with The Post, Cook said he remained conscious, but began to bleed out.

Under fire, Waltz crawled into the back of the Humvee and applied a tourniquet to Cook’s leg just below the crotch, tying it so tightly that it tore muscle, ligaments and tendons, according to Cook. The wounded medic said he was drenched in blood and in the “worst pain of my life.” But the tourniquet worked and the bleeding slowed.

Yet they weren’t out of danger. Moments later, Cook recalled, he saw Waltz briefly knocked cold by a Taliban rocket that landed nearby. “I looked over and he had dirt and black s--- all over his face and eyelids,” Cook said. “But then he got up, kind of shook it off and started returning fire.”

Miraculously, the convoy escaped without suffering any fatalities. Cook and two UAE soldiers were evacuated by helicopter to a field hospital.

Despite the ambush, Waltz and the UAE commander wanted to continue with their original mission, Waltz wrote in his book. The convoy regrouped and prepared to drive onward to Musa Qala, 30 miles to the north.

When Waltz radioed their plan to headquarters, however, the staff warned him that the firefight in Sangin was just a taste of what lay ahead. Surveillance aircraft showed a larger Taliban force massing nearby, according to Scott Mann, an Army lieutenant colonel who was on the headquarters staff.

“Of course, like a good Special Forces captain, he wanted to push on,” Mann, now retired, recalled in an interview. “I said, ‘Hey man, you’re going into a buzz saw. In fact, you’re in the buzz saw.’”

This time, Waltz listened and the convoy turned around. Over the following 12 hours, his team narrowly eluded Taliban fighters in close pursuit, thanks in part to a U.S. Air Force AC-130 gunship that arrived in time to wipe out two groups of insurgents. “His guys were really pinched,” Mann said in an interview. “I still get chills thinking about it because it was very, very bad.”

For his actions, Waltz was awarded a Bronze Star with a “V” device, denoting valor in combat. Cook, the medic, said he thought Waltz deserved additional recognition.

Years later, he offered to help nominate Waltz for a Silver Star, the U.S. military’s third-highest war decoration, for gallantry in action. But Waltz demurred. “He just said something to the effect of, ‘I’m not a medal chaser. Don’t do that,’” Cook recalled.

Cook said he remains a fervent admirer of Waltz — even though he’s not a fan of Trump.

“I’m not at all on the same political wavelength as Mike Waltz, but he saved my life that day and his bravery was unquestionable,” he said.

Waltz returned to his civilian job at the Pentagon in late 2006 and grew frustrated by a disconnect between how senior officials in Washington viewed the war and what he had observed in the field.

In his first book, Waltz wrote that the war had become “rudderless” because the Bush administration was preoccupied with the war in Iraq and had “basically outsourced” Afghanistan to NATO allies. Waltz strongly felt NATO was not up to the task. He had dealt with French, Dutch and other NATO troops in Afghanistan and found them risk-averse, difficult to coordinate and badly equipped.

In his interview with The Post, Waltz said his experiences with NATO forces left a lasting impression — one that echoes Trump’s harsh criticism of the military alliance.

“NATO was a phenomenal alliance in deterring the Cold War,” Waltz said. “But to see what a sad state their equipment has become and how politicized their chain of command was operationally in the field has certainly impacted my views now.”

At the Pentagon, Waltz took a new policy job as a country director for Afghanistan, then was detailed to the White House to work on counterterrorism issues for Vice President Dick Cheney.

As a junior White House staffer, however, he often bit his tongue in briefings when generals gave rosy assessments about how the war was unfolding, he said in his oral history interview. He became especially irked when they exaggerated their progress in training the Afghan security forces, a keystone of the U.S. war strategy.

Waltz said he witnessed “general after general saying, ‘Mr. President, I can turn this military, this Afghan army, around on my watch.’ And I knew they were full of it.”

At the outset of the Obama administration, Waltz briefly returned to his civilian job at the Pentagon. In March 2009, however, his National Guard unit mobilized again and he deployed for a third time to Afghanistan, this time as a major.

Obama had campaigned on a promise to fix the war and eventually boosted the number of U.S. troops to 100,000. In his books, Waltz wrote that the wave of reinforcements created a new set of problems, including a top-heavy and unresponsive chain of command. As a company commander, he sometimes needed to obtain authorizations from 12 different offices before his Special Forces teams could conduct raids against Taliban targets.

He also disagreed with Obama’s strategy for exiting Afghanistan, according to his memoirs. The president announced the troop surge would be temporary, to buy time for the Afghan government to build up its forces and pressure the Taliban into peace talks. Waltz felt the United States needed to make an open-ended military commitment and not let up in Afghanistan. Unlike many in Washington, he still believed the Taliban could be defeated outright.

“The underlying theme of everything we were discussing seemed to be how to end the war rather than how to win it,” he wrote in “Warrior Diplomat,” his 2014 book.

Disenchanted with Obama’s policies, Waltz resigned from his civilian government job in 2011. While he remained a reservist in the Army, he co-founded two private-sector companies in the field of national security.

One was Askari Associates LLC, a small geopolitical consulting firm. The other was Metis Solutions LLC, a Virginia-based defense contractor that ultimately earned him millions of dollars, documents show.

According to federal contracting records, Metis operated primarily at first as a services provider for the U.S. Special Operations Command, which is headquartered in Tampa. In 2016, a Northern Virginia venture capital firm, Blue Delta Capital Partners, invested in Metis, fueling an expansion.

With Waltz as CEO, the company grew from a handful of staff to 400 employees, with operations in 20 states and nine countries, according to a podcast interview that Waltz gave last year.

Kevin Robbins, a general partner at Blue Delta, said the firm invested in Metis because it was impressed with Waltz’s management skills, calling him “a very tough Green Beret.”

“We were writing a check to back Mike and the team and take the company to the next level,” Robbins said. “It was a phenomenal run.”

Metis obtained other federal contracts, including from the Treasury Department. Much of its work focused on analyzing how terrorist networks raise money. The Defense Department also paid Metis to send advisers to Kabul to work alongside Afghan ministries, records show.

Waltz sold his stake in the company when he ran for Congress in 2018, ultimately netting him between $5 million and $26 million, according to a financial disclosure form he submitted in 2020.

Meanwhile, Waltz’s credentials as a Green Beret and Afghanistan veteran opened doors for him in the media world.

The impetus was a 2014 deal negotiated by the Obama administration for the release of Bowe Bergdahl, an Army private whom the Taliban had held prisoner for five years. When Bergdahl was freed, Obama met with his parents in the White House Rose Garden and praised the soldier as a hero.

The description angered Waltz, who went public in interviews with his concerns. Waltz had led Special Forces teams that carried out an intensive — and risky — search for Bergdahl in 2009 when he went missing from a tiny outpost in eastern Afghanistan.

Though the circumstances surrounding Bergdahl’s disappearance were murky at the time, Waltz and others viewed him as a deserter who had endangered hundreds of U.S. personnel by forcing them to conduct a search in hostile territory. Bergdahl later admitted that he abandoned his post because he was unhappy with conditions in the Army. He was captured by the Taliban shortly afterward.

A telegenic Green Beret, Waltz soon found a regular home on Fox News, where he expanded his repertoire beyond the Bergdahl case to become a national security commentator and a critic of Obama’s foreign policy.

In January 2018, he used his perch on Fox to declare his candidacy for Congress. Brian Kilmeade, a host on Fox & Friends, was effusive. “If you want a guy that’s good on business, good on camera, who served in the military with distinction, you’re looking at him,” Kilmeade said.

Waltz defeated Democrat Nancy Soderbergh in November 2018, making him the first Green Beret to win a seat in Congress. Though Waltz did not deploy again to Afghanistan, he remained in the Army National Guard until 2023, when he retired as a colonel. Over his 26-year military career, he received four Bronze Stars, including two with the “V” device for valor, according to his Army service records.

During his first term in Congress, Waltz bonded with Trump on a May 2020 trip to Cape Canaveral, Florida, to observe the launch of the SpaceX Crew Dragon and two astronauts to the International Space Station. Their relationship strengthened during last year’s presidential campaign.

In August, Trump visited Arlington National Cemetery to mark the three-year anniversary of a suicide bombing that killed 13 U.S. service members and 170 Afghans at the Kabul airport.

Federal law prohibits election-related activities at the hallowed site. A Trump campaign staffer got into an altercation with an Army official who tried to block the operative from recording video of Trump amid the gravestones.

The dustup kindled a national debate over whether Trump was politicizing the deaths of U.S. military personnel — or, in his supporters’ view, trying to hold the Biden administration accountable for botching the conclusion of the war.

One of the loudest voices defending Trump belonged to Waltz, who joined him at Arlington for the commemoration. Despite their past differences over Afghanistan, the retired Army colonel had built a rapport with Trump and introduced him to relatives of some of the fallen troops being honored that day. (While several of the Gold Star families supported Trump’s role at the ceremony, others declined to take part).

“Those families wanted him there,” Waltz said in an Aug. 30 interview on Fox News with Pete Hegseth, a talk-show host and fellow Afghanistan war veteran whom Trump has since nominated to serve as defense secretary. “And damn it, they deserve to have whatever they want.”

Alex Horton and Nate Jones contributed to this report.