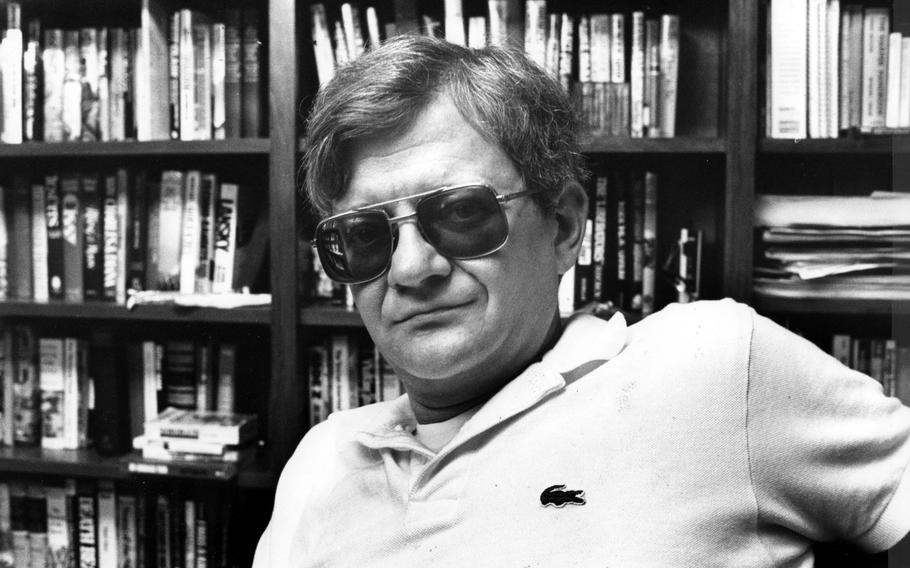

Tom Clancy’s book “The Hunt for Red October” was released 40 years ago this month. (Bob Farley/The Washington Post)

The 37-year-old insurance salesman said he had no expectations of writing a bestseller. He just wanted to publish a book after years of dreaming about it — “to get that monkey off my back,” Tom Clancy would tell an interviewer years later.

But when “The Hunt for Red October” was released 40 years ago this month — plunging readers aboard a Soviet nuclear-missile submarine whose captain was seeking to defect to the United States — Clancy would take his first step toward building one of America’s most unlikely publishing empires.

The rural Marylander had almost no written works to his name. He had never seen the inside of a submarine. His publisher, housed on the grounds of the U.S. Naval Academy, had never released a novel — and the military officer who reviewed the manuscript worried that “The Hunt for Red October” would be a national security risk and advised against publishing.

Still, Clancy’s book was here, arriving in area bookstores. And his opening chapter began with an apt three words: “The First Day.”

Three weeks later, a Washington Post critic pronounced the book “breathlessly exciting,” a glowing review that helped make Clancy’s reputation. A subsequent endorsement by President Ronald Reagan — who was reported to have called the book a “perfect yarn” — would cement it.

Within the year, Clancy would be celebrated at the White House, meet the president and emerge as a kind of spokesman for Reagan-era policies. Tall, typically seen in aviator sunglasses, Clancy’s arrival as a national figure coincided with a surge of mid-1980s patriotism in pop culture; as his books began to dominate bestseller lists, the Tom Cruise-starring “Top Gun” and other military-themed films sold out movie theaters.

And as Clancy churned out more blockbusters — with four books topping bestseller lists across the following three years — he was credited as the creator of a new genre of fiction, blending military acronyms and technological breakthroughs.

“Tom Clancy has a genius for big, compelling plots, a passion for research, a natural narrative gift, a solid prose style, a hyperactive, Mitty-esque imagination and a blissfully uncomplicated view of human nature and international affairs,” the New York Times wrote in 1988, dubbing him “king of the techno-thriller.”

His work would soon transcend the printed page. Over the ensuing decade, a film series starring Alec Baldwin, Harrison Ford, Sean Connery and James Earl Jones, among other actors, would win more fans for Clancy’s books and characters — even as the increasingly famous author entered into a stunningly public fight with Hollywood over how his books were adapted for the screen.

Success brought wealth — a sprawling Chesapeake Bay estate with a tank out front; a significant ownership stake in baseball’s Baltimore Orioles — and influence. Clancy said he turned down repeated invitations from politicians to run for Congress as a Republican.

Fortune and fame also revealed contradictions. A detail-obsessed author who berated filmmakers for minor inaccuracies would increasingly devise fantastical plots to serve his books. (His everyman hero Jack Ryan — spoiler alert — rises from CIA analyst to U.S. president across a decade of Clancy’s novels.)

A nearsighted, self-described nerd who never served in the armed forces would encase himself in military paraphernalia and bid to become a major player in American sports. A husband who stressed family values in interviews would divorce his first wife amid rumored affairs, launching a long-running legal battle over his fictional characters in a case known as Clancy v. Clancy.

Tom Clancy died 11 years ago this month, but the universe he created lives on. A stable of authors still write books under his name; a video game studio continues to churn out a series of “Tom Clancy”-branded video games. A “Jack Ryan” TV show on Amazon Prime drew millions of viewers before ending last year.

But it all began with a Washington Post article — and a real-life attempt to defect from the Soviet Union.

The birth of ‘Red October’

In 1976, a foreign correspondent for The Post revealed that there had been a mutiny aboard the Storozhevoy, a Soviet navy frigate that tried to sail for Sweden. But at a time of global tensions between the Soviets and their Western rivals, there was limited information about what had really happened aboard the ship. Clancy read The Post’s brief article, and his imagination filled in the rest.

Six years later, a U.S. Navy officer named Gregory Young published a master’s thesis about the Storozhevoy mutiny, piecing together the true story and revealing the motivations of the crew, including how the ship’s political officer had orchestrated the attempted defection. In an interview last month, Young said he had no reason to think that anyone — outside of his mother and thesis adviser — would actually ever read it.

Then he received a letter from an insurance salesman.

“I am a private businessman who finds business rather dull,” Clancy wrote.

Now, after years of researching naval warfare and soaking up stories — including from ex-submariners who worked at the nearby Calvert Cliff Nuclear Plant and bought their life insurance from him — Clancy was trying to finish his novel about the defection of a Soviet nuclear-missile submarine, or SSBN. (Standing for “Ship, Submersible, Ballistic, Nuclear.”) And he was turning to the Navy officer, stationed in the Philippines, to help him.

“Posit: Red October, a modified Typhoon-class SSBN is attempting to defect to the U.S. The Soviets find out. We find out. Chaos results,” Clancy wrote to Young, asking for feedback and sharing insights into his process. (Such as how a longtime Baltimore Colts quarterback inspired the ethnicity of his fictional submarine’s captain.)

Clancy — who had negotiated for a $5,000 advance on his book — worked on it steadily into 1983. It was set to be the first novel ever published by the then-111-year-old U.S. Naval Institute, an independent offshoot of the Naval Academy that was best known for its professional articles, analysis and manuals.

At The Post, the book was reviewed by editor Reid Beddow, a military veteran who persuaded his colleagues to take a chance on a first-time novelist from a little-known publishing house, and then did the same for the paper’s readers.

“’The Hunt for Red October’ is a tremendously enjoyable and gripping novel of naval derring-do,” Beddow wrote. It was a key endorsement when The Post’s “Book World” section had the power to make — or break — writers’ careers. By November, the book was on local D.C. bestseller lists and was winning fervent fans. Nancy Reynolds, an influential Washington lobbyist, reportedly shared the book with first lady Nancy Reagan, who then gave it to her husband.

By early 1985, it was national news that the U.S. president had read Clancy’s book — and loved it.

Clancy took to the moment, bantering with Reagan in an Oval Office meeting and being celebrated at a luncheon in the White House’s Roosevelt Room. But he claimed the attention was surreal and returned to selling insurance while working on more books.

“I have 1,000 clients. I can’t walk away from them,” Clancy told the Los Angeles Times in August 1986.

Fame, fortune and family pains

Clancy’s calculus quickly changed, thanks to more bestsellers like “Red Storm Rising” and multimillion-dollar book advances from his new publisher, Putnam Publishing Group. He switched to full-time writing and escalated his output.

He also broke through in Hollywood. After years of production delays, “The Hunt for Red October” became the top movie in America for three weeks in March 1990.

Forbes magazine estimated that Clancy’s annual income reached $50 million by the mid-1990s. By the end of the decade, he would be paid about $25 million by his publisher for every new hardcover title he delivered.

The money allowed him to buy fast cars, fancy homes — even a 25% stake in the Orioles baseball team. The fame gave him a platform to pontificate in speeches and essays on matters such as gun control (he was against it), the privatization of the U.S. space program (he was for it), and personal morality.

“If a guy cannot manage his family successfully — be a good husband, be a good father — then why the hell would we trust him to do anything else?” Clancy said in a 1991 interview for “The Tom Clancy Companion,” a guide to his works.

Actors such as Tom Selleck befriended him; rising GOP leader Newt Gingrich and other politicians sought him out for advice.

But as Clancy’s star power rose, his personal intrigues began to rival his fictional dramas.

He fought with his first publisher, the Naval Institute, over who owned the rights to the character “Jack Ryan.” (Clancy settled the case in 1988 by paying the institute $125,000.)

He battled with Hollywood as a second book-turned-movie, “Patriot Games,” went into production in 1991. Clancy said that he wrote memos — 14 pages, single-spaced — complaining about details, such as a scene that called for characters to look east at the sunset off the Chesapeake Bay. He also insisted that casting Harrison Ford to play Ryan was a mistake, saying that at 49, Ford was almost two decades too old. Paramount Pictures effectively froze Clancy out of the making of the next film in the series, “Clear and Present Danger.”

And Clancy fought with family. His divorce became fodder for tabloids as well as intellectual property lawyers, fascinated by his wife’s claims of ownership to Clancy’s characters and future work. The fallout would kill his bid to own the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings; it also would spark two decades of family legal battles that persisted after Clancy’s death.

Meanwhile, Clancy’s books remained bestsellers — but had grown longer and increasingly unwieldy, a point picked apart by critics. Patrick O’Brian, author of an acclaimed series of novels on British naval warfare, including “Master and Commander,” was recruited by The Post’s Beddow in 1991 to offer a verdict on Clancy’s latest book: the 798-page “The Sum of All Fears.”

“There is no doubt that Clancy is a brilliant describer of events,” O’Brian wrote in his review, before criticizing his “verbose” writing and suggesting that the book was 200 pages too long.

Leaving an imprint

Forty years after Clancy first surfaced, he continues to leave ripples in his wake.

“The Hunt for Red October” has sold more than 500,000 hardcover copies for the Naval Institute, Scot Christenson, the institute’s director of communications, wrote in an email. Its success also teed up more fictional bestsellers for the small press, including the 1986 novel “Flight of the Intruder” — another military thriller that became a Hollywood movie.

In an email, a spokeswoman for Putnam said that Clancy’s books had sold “many, many millions of copies” for the publishing house. Two more Clancy-branded books featuring Jack Ryan and his son, Jack Ryan, Jr., as the protagonists are close to publication.

Young — the former Naval officer who helped Clancy on several books — ended up writing his own book on the true story of the mutiny that inspired “The Hunt for Red October.”

But while the Clancy-built machine rolls on, the author’s absence is sometimes noticeable.

The Amazon TV show — with Ryan played this time by actor John Krasinski — opens with Ryan’s highly unrealistic commute to work, starting in Georgetown, heading to Capitol Hill, before presumably turning around and then heading to the CIA’s offices in Virginia. It’s the kind of error that would have had the accuracy-obsessed Clancy firing off a memo.