Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen. Eric M. Smith salutes during ceremonial colors at the 40th Beirut Memorial Observance Ceremony at Lejeune Memorial Gardens in Jacksonville, North Carolina, Oct. 23, 2023. The memorial observance is held annually on October 23 to remember the lives lost in the terrorist attacks at U.S. Marine Barracks in Beirut, Lebanon and Grenada. (Zachary Zephir/U.S. Marine Corps)

JACKSONVILLE, N.C. — Behind the stone walls here of the Beirut Memorial, fog filtered in Saturday through a grove of Bradford pear trees planted 40 years ago to commemorate the deaths of more than 270 U.S. troops who were killed in a series of militant attacks in Lebanon.

Steve Aiken, a retired Marine Corps sergeant major, reflected wistfully on Oct. 23, 1983, the date when truck bombs targeted two buildings housing American and French troops, killing 241 U.S. service members and 58 French troops. Then a young lance corporal, Aiken was off the coast aboard the USS Inchon as wounded service members were transferred to a fleet of American vessels that provided medical treatment.

Memories like Aiken’s came flooding back after Israel announced on Friday that Ibrahim Aqil, a Hezbollah commander, was among those killed in an Israeli airstrike carried out earlier in the day. U.S. officials have said he was a principal member of a terrorist cell that carried out a wave of violence that included the bombing on the Marine barracks in October 1983, the bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut that April that killed 63 people, and the kidnapping of German and American hostages in Lebanon.

For Americans still bearing scars from the attacks in Lebanon more than 40 years ago, the killing, since confirmed by Hezbollah, feels like a belated measure of justice. The decades gone by have underscored the enduring nature of the losses, as those remaining cope with the loss of children, parents, grandparents and more.

“You know, my story is just one of those tiny tragedies. Big tragedy for me. Big tragedy for my family,” said Catherine Votaw, whose father Albert, 57, was killed in the embassy bombing in April 1983. “Everybody suffered these tremendous tragedies that blew their lives apart.”

The bombings — and several smaller deadly attacks on U.S. troops — took place after the Reagan administration deployed U.S. troops to Lebanon in a nebulous peacekeeping mission in 1982 after Israeli forces invaded Lebanon.

The United States withdrew nearly all of its forces in Lebanon early in 1984, just months after the attacks. Some members of the administration later voiced frustration that President Ronald Reagan had made one mistake by putting U.S. troops in harm’s way without adequate protection and then another by not retaliating after.

The Israeli strike on Friday in a Beirut suburb killed at least 37 people, Lebanon’s Health Ministry said Saturday, and came amid a days-long campaign against Hezbollah, which includes both a political party and an Iran-backed paramilitary group that the United States identifies as a terrorist organization.

Israeli officials have said they will continue their operations against Hezbollah until citizens in northern Israel are safe to return to their homes without cross-border attacks. Simultaneously, Israel is pressing on with the war in Gaza, which has killed tens of thousands of people and was spawned by an attack on Hamas militants nearly a year ago.

Hezbollah was founded in 1982, as violence against U.S. troops in Lebanon spiked. In addition to its roles in the major bombings of 1983, the militant group was involved in the bombing of the U.S. Embassy annex in Beirut in 1984 that killed 23 people, the hijacking of TWA Flight 847 in 1985 and the Khobar Towers attack in Saudi Arabia in 1996 that killed 19 U.S. airmen, according to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

“We’ve been engaged with Hezbollah for a very long time,” said retired Amb. Ryan Crocker, who survived the April 1983 embassy bombing while stationed there. Of Aqil, he said, “It is still a source of some satisfaction that he finally got it.”

Crocker, 75, was a political attaché in his fourth-floor office when a suicide bomber with a van packed with explosives careened into the front of the building and detonated. Among the 63 killed that day were 17 Americans, including CIA personnel, a Marine, embassy staff and a journalist who had been visiting the building.

Crocker said he saw a bright flash of light through his window and was thrown against a wall by the force of the blast. He initially thought a rocket-propelled grenade had hit the building and realized it was something much larger when he left his office and saw the Mediterranean Sea through where the CIA station in the building had stood. It was pitch-black as he went downstairs, he said, “except for the fires.”

Crocker, who went on to serve as the U.S. ambassador to Syria, Iraq, Pakistan, Kuwait, Afghanistan and Lebanon, warned that “actions and reactions, and reactions to the reactions, can go on in a seemingly endless chain.”

“It is not,” he said, “the end of the story.”

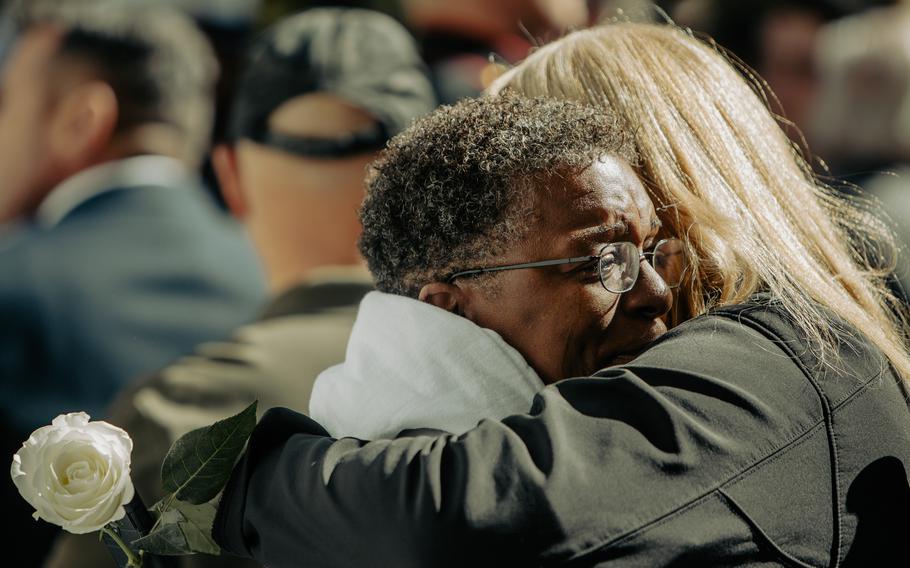

Thomasine Baynard, the spouse of Lance Cpl. James R. Baynard, a fallen communications specialist with 1st Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division, embraces a loved one following the 40th Beirut Memorial Observance Ceremony at Lejeune Memorial Gardens in Jacksonville, North Carolina, Oct. 23, 2023. (Zachary Zephir/U.S. Marine Corps)

Among those killed in the embassy attack was Albert Votaw, a housing officer with the U.S. Agency for International Development who had arrived in Beirut just 11 days earlier. His daughter Catherine said that it was years before she could say her father’s name without crying. She eventually named her second-born son after him.

Votaw said in an interview Friday night that she was shocked that Aqil had been alive for so long.

“I’m not a person who believes in capital punishment,” she said. “I don’t wish death on anybody, even my very worst enemies. It’s hard not to find some justice in him being dead. My only question is, you know: Why 41 years? How did he get to live 41 years longer than my dad?”

Votaw said sorrowfully that her father was robbed of the opportunity to meet his eight grandchildren. When the bombing occurred, her mother was still in Thailand, where her father recently had been posted, and it took days for the immediate family to be reunited. Her mother, Estera, a Holocaust survivor, died at 83 in 2012 and struggled with the grief of his loss for the rest of her life after settling as a widow in Washington’s Dupont Circle neighborhood.

“She told me once that she dreamt about him every night and woke up to realize he was dead,” Votaw said, choking up.

The traumas of the Marine barracks bombing are especially acute in Jacksonville, the coastal North Carolina town that is home to Camp Lejeune, a sprawling installation from which most of the U.S. troops had deployed with 1st Battalion, 8th Marines, an infantry unit that has since been nicknamed the “Beirut Battalion.”

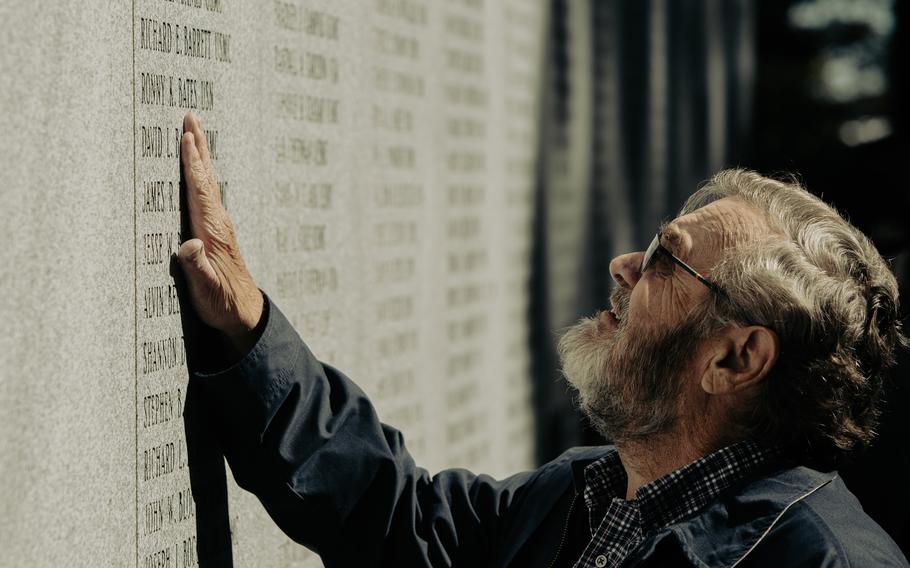

At the memorial on Saturday morning, walkers, joggers and parents with young children passed the monument. A few lingered to read the names of the dead.

A family member of a fallen service member pays his respects following the 40th Beirut Memorial Observance Ceremony at Lejeune Memorial Gardens in Jacksonville, North Carolina, Oct. 23, 2023. The memorial observance is held annually on October 23 to remember the lives lost in the terrorist attacks at the U.S. Marine Barracks in Beirut, Lebanon and Grenada. (Zachary Zephir/U.S. Marine Corps)

Aiken, who had been off the coast when the barracks was attacked, said the killing of Aqil more than 40 years later was “God’s judgment” and would send a message to Iran and other countries sponsoring terrorism.

“You might get away, but you’re not going to get by,” he said. “Our memory is long. Israel’s is even longer.”

At a nearby diner, Ray Mayer, a retired Navy chief petty officer, recalled watching at nearby Marine Corps Air Station New River as his squadron was called out of its barracks to get ready to fly to Beirut on a rescue mission. Mayer said he remained behind with other assignments.

“There were a lot of Marines, just kids really, who got killed over there,” said Mayer, who retired in 1986. “It was sad. They came in peace. And that bombing was the start of the wars that followed.”

James Lariviere, a retired Marine Corps general, said in a phone interview that he wonders whether the United States had a role in helping the Israelis find Aqil.

Although he deployed to Beirut as a lieutenant in 1982 and rotated home before the bombings the following year, the killing of Aqil still resonates with him, he said. He has always wondered, he said, why the United States never retaliated after the Marine barracks bombing.

Lariviere has been working on a thesis project about the U.S. experience in Beirut. He has been struck, he said, by how little senior U.S. officials adjusted security after the embassy bombing in April 1983.

“I have yet to find a good explanation for it in anything I’ve ever looked at,” he said. “It’s just striking.”

Working on his project, Lariviere interviewed retired Gen. Alfred M. Gray Jr., who was based in North Carolina when the bombing occurred but had visited his Marines and was among those who did not foresee the severity of the threat, Lariviere said. Gray, who died earlier this year, went on to transform the Marine Corps as commandant in the bombing’s aftermath, vowing to raise standards in the service and never let Marines deploy again without a clear mission.

“When I asked him about the bombing,” Lariviere said, “the only thing he would say was, ‘Sometimes you just get beat and we got beat. We didn’t see it coming.’”

Lamothe reported from Washington.