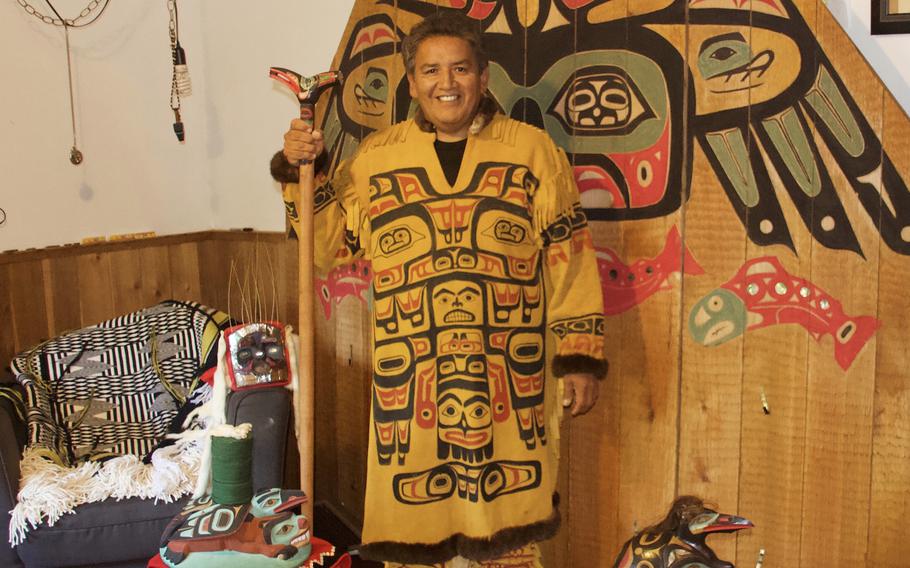

Kaaxooutch, who also goes by Garfield George, with the beaver prow in Angoon, Alaska, in 2018. (Courtesy of Garfield George)

Billy Jones stood overlooking the Alaskan village of Angoon and took stock of what the U.S. Navy had wrought.

Long spruce houses blasted apart by U.S. warships. Food stores burned. The U.S. troops responsible had gathered canoes — the village’s lifeblood — and smashed them to pieces. At least six children died, according to historical accounts, asphyxiated by the smoke of their smoldering homes.

Jones, then 13 years old, committed to memorializing what he witnessed in October 1882, including how fellow members of the Deisheetaan clan would later die of hunger and exposure. Before his death in the 1960s, Jones shared the story with others in the community, including a young boy who would grow up to become a prominent local leader and help preserve the oral history and its sorrowful final lines:

Wul-laa-xooooo

Almost all the people starved

A-adeiiiiii yei yu toowunnooku ye

This is how we were wounded in mind, body, soul and spirit

On Saturday, the Navy will issue the first of two formal apologies to the Lingít communities (also called Tlingit) who its forces targeted in harrowing assaults on Kake in 1869 and Angoon 13 year later. The message will be delivered by Rear Adm. Mark Sucato, a senior officer overseeing the Navy’s shore presence in Alaska.

The apologies are a rare concession from the U.S. military. American troops committed atrocities against Native people for decades, and in many cases celebrated their deaths as achievements. To that end, the Pentagon also has undertaken a review of close to two dozen battlefield commendations awarded for actions in the 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee.

In a statement, Navy officials acknowledged that its “wrongful” actions at Kake and Angoon had “inflicted multigenerational trauma.” A spokeswoman, Julianne Leinenveber, said the “pain and suffering inflicted upon the Tlingit people warrants these long overdue apologies.”

In interviews, community leaders in the isolated islands south of Juneau, Alaska’s capital, said they welcome the gesture but also called attention to enduring challenges.

“It will mean a lot,” said Garfield George, who as house master of Deishú Hít, or End of the Trail House, is known as Kaaxooutch. He will help lead the ceremony in Angoon on Oct. 26 to commemorate the attack’s 142nd anniversary. The Navy’s apology, George explained, will correct the record and finally wipe away what he called long-standing exaggerations and lies.

“The way they wrote it up” in official military accounts, George said, “it was like we deserved what happened to us. And that’s just not true.”

The Lingít people, along with other local tribes, trace their lineage to the Alaskan panhandle, west of British Columbia, dating back at least 10,000 years. The communities there, dependent on subsistence living, harvested salmon, cod and herring from the Pacific Northwest’s frigid waters, and dried fish and meat ensured their survival through winter.

The tragedies in Kake and Angoon were set into motion after the Alaskan territory was purchased from Russia in 1867, putting the region under the control of the federal government with the U.S. Army and Navy providing oversight early on. In 1869, after a period of simmering tension between the Lingít people and American soldiers, a sentry at the military fort in Sitka killed two unarmed Lingít men in a canoe. In accordance with local customs, a leader from the clan demanded blankets and other goods as recompense, but American commanders refused. The Lingít then captured four fur traders and killed two to settle the dispute.

The Army dispatched the USS Saginaw that February. The sloop-of-war trained its guns on Kake, and afterward troops went ashore to torch the village.

“They burned everything. All the shelters, all the food caches, the canoes,” said Joel Jackson, president of the Organized Village of Kake. While no one was killed in the bombardment, the eradication of boats and food supplies in wintertime condemned the community to suffering.

“We know we lost people,” Jackson said. The episode became known as the Kake War, a misnomer, Jackson said, because it was a one-sided attack against civilians.

U.S. Army officials are in talks with local leaders to make “a meaningful and appropriate apology” for a separate assault that year that devastated the Lingít village of Wrangell, spokesman Matt Ahearn said. “Our goal,” he added, “is to build trust and support long-term healing.” Ahearn said the Army’s focus is on the violence in Wrangell and deferred to the Navy questions about what happened at Kake.

Thirteen years later, a medicine man named Til’xtlein from the nearby settlement in Angoon was killed in an explosion aboard a whaling ship. Though the death was an accident, Lingít custom was to seek payment “equal to his stature,” said his descendant Eunice James. The sum: 200 blankets.

As in Kake years earlier, misunderstanding shaped what happened next, James said. Military officials wrongly sensed the tribe was preparing for war, their fears buttressed by claims that two White men had been kidnapped and held for ransom. Community leaders have long disputed this, maintaining that although the Lingít confiscated whaling boats during their period of mourning, the vessels were returned. Historians, too, have concluded an abduction was unlikely to have occurred as there was never any report of an attempted rescue or other details to support such a claim.

E.C. Merriman, commander of U.S. forces in the region, rejected the Lingít appeal for 200 blankets. Instead, he demanded twice that number from them — by the next day — and said he would destroy Angoon if they did not comply, according to government accounts from the time. It is unclear whether community leaders understood the ultimatum, and when they provided only a fraction of what was sought, Merriman ordered the assault.

“The military responded probably the only way they knew how,” James said, “without having an understanding of the culture and the people and the language.”

Jones, the boy who witnessed Angoon’s destruction, was helping his mother prepare the community’s herring catch for winter storage when the attack occurred, he later told an anthropologist. “They left us homeless on the beach,” he recounted. Washington deemed it a success.

“As long as the native tribes … do not feel the force of the government and are not punished for flagrant outrages, so much the more dangerous do they become,” William Morris, the region’s federal revenue collector, wrote in a letter to the U.S. treasury secretary praising Merriman.

A single canoe with a beaver carved into the prow survived — a salvation for the community, who used it for collecting timber to rebuild their homes and boats, and to gather new food, said George, the community leader in Angoon who carries on its oral history. When the canoe was no longer usable, it was cremated like a person.

The beaver prow later disappeared under mysterious circumstances and was sold to the American Museum of Natural History in New York with little detail about its origin, the museum says. The beaver was repatriated in 1999 and is once again celebrated in ceremonies to honor “The Canoe That Saved Us,” George said.

The community in Angoon received a $90,000 and 23,000 acres in a settlement with the Department of the Interior in 1973, but an apology remained elusive. A spokesperson for the agency declined to comment for this report.

Leaders in Angoon and Kake say the attacks are but one calamity in a series of injustices tied to the Americans’ arrival. Diseases took hold, and alcoholism remains a scourge. There is little infrastructure — Kake and Angoon are reachable only by seaplane or ferry — and high unemployment.

Jackson, the village president in Kake, said local leaders have yet to decide whether they will accept the Navy’s apology, noting there are additional needs they would like the federal government to address.

“It’s a start of what they need to do to help us heal our people,” Jackson said. “But by no means can it erase what they did.”