The Marriner S. Eccles Federal Reserve building in Washington on July 6, 2022. With inflation cooling and worries about the job market spreading, the central bank is expected to announce a long-awaited rate cut next week. (Al Drago/Bloomberg)

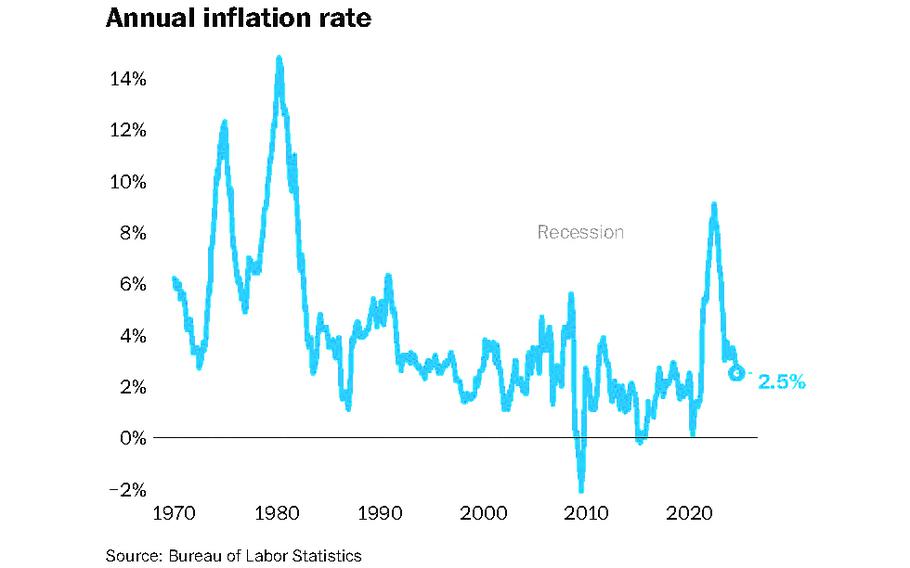

Inflation eased again in August, dropping to the lowest level in more than three years and locking in expectations that the Federal Reserve will cut interest rates next week for the first time since the pandemic’s early days.

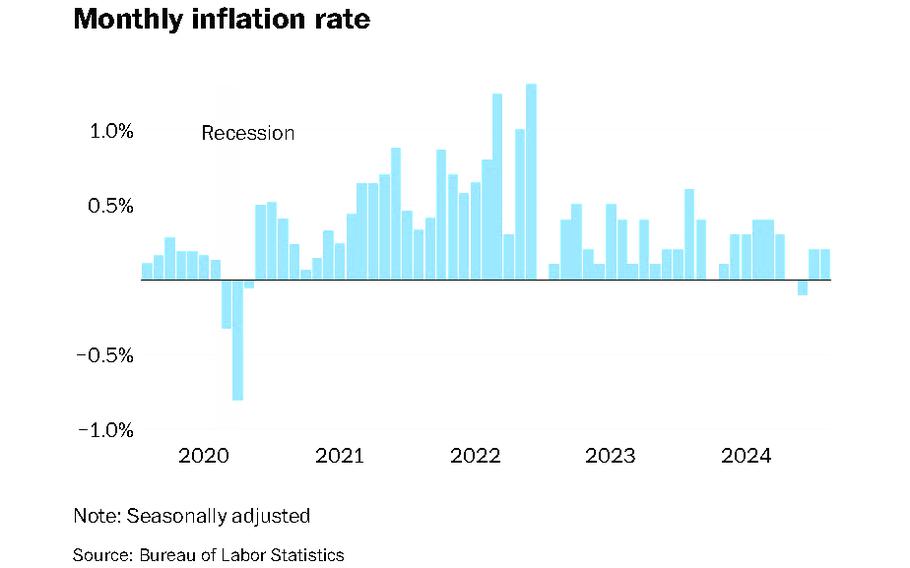

Data released Wednesday by the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed prices climbed 2.5% in the 12 months ending in August. That was a noticeable improvement over the 2.9% notched in July, in part because of falling gas prices. Prices also climbed 0.2% over the previous month.

Housing costs accounted for more than 70% of the overall year-over-year increase. However, policymakers are skeptical that the measures reflected in the consumer price index offer an up-to-date snapshot of that market. Other real-time indicators have shown rents easing considerably, or even falling, in major cities for much of the year. But the Fed will be hard-pressed to wrestle inflation down to normal levels until official statistics fall in line. According to the BLS, two key rent gauges are showing little relief compared to previous months.

“The heat in today’s report is not one that will give the Fed pause,” said former Fed economist Claudia Sahm. “It’s more like, ‘you’ve got to be kidding me.’”

Costs for eggs popped last month, along with airfares, car insurance and clothing. A closely watched measure of inflation that strips out more volatile categories like food and energy — known as “core inflation” — also came in a smidgen higher than July.

(The Washington Post)

But a drop in energy prices helped nudge overall inflation in a cooler direction, with the energy index falling 0.8%, after being unchanged the preceding month. Gas prices were down 10.3% compared with last year. Indexes for used cars and trucks, household furnishings and medical care also showed improvement.

Over the past few years, economists and policymakers have been partial to a slew of extremely specific inflation measures that examine the economy from all angles. And for months now, officials have leaned toward gauges that separate out housing data. A Wednesday blog post from the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers showed that while core inflation rose 3.2% over the past year, that measure clocked in at a low 1.8% when cutting out housing.

“What these housing price trends show about a structural supply shortfall in the U.S. housing market,” the CEA wrote, adding: “the sooner we can get this agenda underway, the better for American households.”

Inflation has fallen steadily since peaking at an annual rate of 9.1% two years ago. But the long stretch of sharp increases has left prices much higher than before the pandemic, leaving scores of households and businesses with the feeling that the economy isn’t working for them. In the run-up to the presidential election, Kamala Harris and Donald Trump are pitching voters on their plans to lower prices, including for housing and other everyday costs. But some economists fear that the candidates’ policies could exacerbate inflation, especially if Trump returns to the White House and carries out his pledges for mass deportations and high tariffs. Harris’s plans to help people get into the housing market through tax credits and other incentives could also push prices skyward, though the campaign also talks about building more homes to meet increased demand.

Still, the Fed’s interest rate moves tend to affect inflation more than anything the president has direct control over. And while central bankers say they make decisions purely based on economic data — never the political calendar — lower interest rates would probably improve people’s confidence in the economy right as many are preparing to cast their votes. Americans would see relief on mortgage costs, car loans and other kinds of investments, and the stock market would also probably celebrate lower rates.

(The Washington Post)

Still, markets dropped on the latest news, as analysts slashed expectations for a larger Fed cut next week. All three major indexes flashed red shortly after the open.

All told, Wednesday’s snapshot offered the latest assurance that inflation is reliably ticking down to normal levels and is even bringing more widespread progress than earlier phases of the bumpy fight. But the otherwise welcome news is complicated by mounting criticism that the Fed has stayed too focused on inflation for too long, jeopardizing the job market, which could buckle under the weight of high rates.

In his most important speech of the year, Fed Chair Jerome H. Powell last month said “the time has come” for interest rate cuts, all but guaranteeing a move when officials convene Sept. 17-18. But the open question is how aggressively they decide to act. Rates have remained between 5.25 and 5.5% for more than a year, and officials will bring rates down more quickly if they think slowing in hiring and wages is turning into something more worrisome. Last week’s closely watched August jobs report from the BLS showed the labor market was slowing, but at a pace roughly in line with analysts’ expectations.

Fed leaders will ultimately decide between cutting rates by a more typical quarter-point or a stronger half-point next week. They will also probably cut rates later in the year and into 2025. But if policymakers feel they need to issue a more forceful signal at the get-go, they’ll opt for a larger cut sooner.

For now, both options are on the table.

“In light of the considerable and ongoing progress toward the [Fed’s] 2% inflation goal, I believe that the balance of risks has shifted toward the employment side of our dual mandate, and that monetary policy needs to adjust accordingly,” Fed Gov. Christopher Waller said in a speech last week.

The focus on the job market reflects a remarkable shift in the economy since the Fed sprinted to catch up to inflation in early 2022 and ultimately hoisted interest rates to the highest level in more than two decades. That effort was intended to slow the economy and tame rising prices, which strained peoples’ budgets for groceries, gas and rent. And while at times it looked like inflation was heating back up, inflation dropped close to normal levels without a recession or other economic hazards. (The Fed wants inflation to rise 2% each year, but that’s using a different gauge than the one released Wednesday. That measure rose 2.5% in July.)

It remains to be seen, though, whether cracks in the economy still get in the way of a “soft landing.” In July, disappointing jobs figures and a rise in the unemployment rate raised alarms that the Fed was too late to cut rates, with direct consequences for workers and employers. But the August figures assuaged some of those fears, with the unemployment rate ticking down slightly to 4.2%.

Fed watchers expected those August figures would settle lingering questions about the scale of the Fed’s upcoming cut. That didn’t quite happen. But what is clear is that steady progress on inflation has changed the Fed’s approach yet again.

“The time has come for policy to adjust,” Powell said last month. “The direction of travel is clear.”