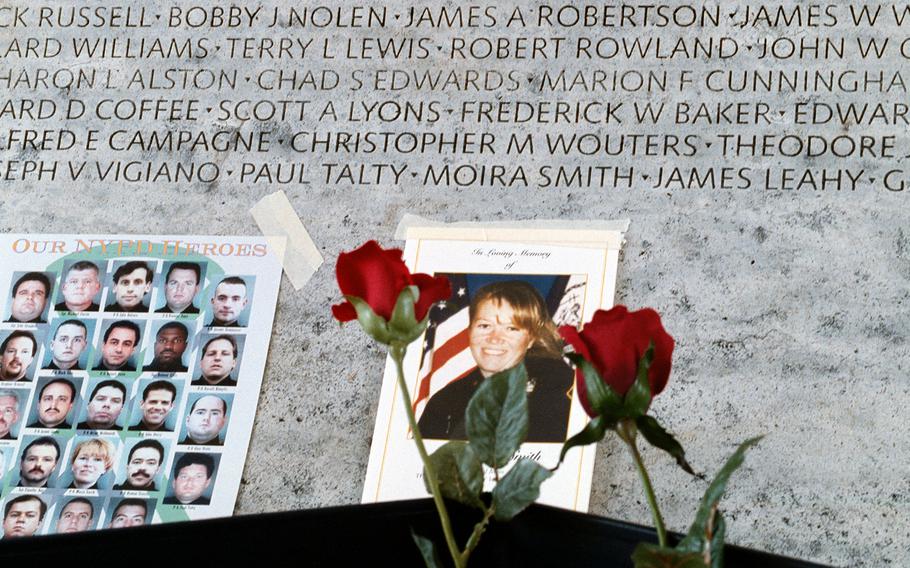

Among the names on the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial at Judiciary Square in Washington is Moira Smith, one of the many first responders in New York City who died on Sept. 11, 2001. (Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post )

The plea deal unveiled this week for three men accused of plotting the deadliest terrorist attack on U.S. soil had outraged Jim Smith. But Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s surprise move late Friday to scrap the agreement didn’t comfort him much, either.

“They’re playing with our emotions,” said Smith, whose wife perished at the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001.

The retired New York police officer had been getting ready for bed when someone called with shocking news for the second time in barely 48 hours: The suspects charged with killing Moira Smith and nearly 3,000 others could no longer plead guilty in exchange for avoiding a possible death penalty.

Smith, 62, had wanted the Guantánamo Bay detainees - who have been in U.S. custody since 2003 - to face the harshest punishment imaginable.

“But now it’s like nobody knows what they are doing,” he said. “It’s hard to trust people when they flip-flop like that.”

The trio had been expected to enter their pleas as early as next week. Austin’s sudden decision nixed that option. His announcement shocked families still trying to process the idea that this 23-year-old case, delayed by allegations of CIA torture and tainted evidence, could end with life sentences for Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Walid bin Attash and Mustafa al-Hawsawi.

Authorities consider Mohammed to be the mastermind of the four airplane hijackings that changed the course of history.

“Effective immediately, I hereby withdraw your authority in the above-referenced case to enter into a pretrial agreement and reserve such authority to myself,” Austin wrote in a memo to the retired brigadier general who’d approved the plea deal.

The case has dragged on for so long that the federal victim liaison that Smith knew best is now retired. Two days earlier, she’d still called him, wanting to explain what would happen with the three men.

His immediate reaction then: How could the accused plotters not be subject to the maximum penalty?

His wife, Moira Smith, a fellow officer and the mother of their 2-year-old girl, was among the first responders who rushed to the scene in Lower Manhattan after American Airlines Flight 11 hit the North Tower and then United Airlines Flight 175 rammed into the South Tower.

Now he wondered if the burst of families’ anger had swayed the Pentagon.

“I think it didn’t poll well,” said Smith, 62. “So they pulled it.”

Word that the suspects could have any say in their fate had offered grieving families little relief. Some had wanted the case against the three men to go to trial, giving relatives the chance to confront the accused and unearth more information about the attacks.

Some were perplexed by prosecutors’ initial invitation to submit questions to Mohammed and his two accomplices - about “their roles and reasons for conducting the September 11 attacks.” Families had 45 days to send their queries, defense officials wrote in the notification letters that went out on Wednesday.

Brett Eagleson had been vexed by what would be lost with a plea deal. He’s sure Americans still don’t know the full story of what happened on 9/11, and he hoped a trial could fill in those blanks.

Late Friday, he said he was glad to see that possibility back on the table, though the Defense Department’s about-face felt like getting jerked around.

“What is going on at the Pentagon right now?” he asked.

Eagleson, 38, was a high school sophomore when his father died in New York. Bruce Eagleson had been working in an office on the 17th floor of the South Tower. He’d called his family after the first plane hit. He’d been trying to help others get out.

The son, now living in Connecticut, has been part of an effort to sue Saudi Arabia, accusing the nation of providing support to the attackers. He wanted to emulate his father, who was not afraid to fight back. On Wednesday, Eagleson had crammed into a Manhattan courtroom with other victims’ families. Their lawyers, they said, had uncovered fresh videos. New potential evidence. What else, Eagleson wondered, was still out there?

“There have been missteps - every step of the way - regarding this case,” he said.

Dennis McGinley, 58, had detested the plea deal. As he mowed his lawn Friday, he couldn’t shake his disappointment and broke down crying. The government, he thought, shouldn’t be negotiating in any way with terrorists.

“Why are we, the 9/11 families, the ones getting punished all the time?” he wondered. “Why are we being treated so unfairly?”

McGinley’s brother Daniel died in the World Trade Center’s South Tower. When another brother called him to tell him of Austin’s decision, he felt a measure of relief. He, too, wants to see a trial.

“Thank God someone has common sense,” he said Saturday morning from his home in Point Lookout, N.Y.

In Greenville, N.C., Bruce Serva had a similar reaction. His wife, Marian, was a congressional affairs contact officer for the Army when American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon.

“I hope this speeds up the trial process,” Serva, 71, said of the Pentagon’s reversal, “and they are found guilty, given the death penalty and are executed promptly after that.”

Jack Grandcolas has tried to focus on the positive over the years. The flip-flop, he said, just made that harder.

“They ask us to digest this plea deal,” he said, “and then they make us throw it back up.”

In the chasm of time since his wife boarded United Airlines Flight 93 - the plane that went down in rural Shanksville, Pa., after passengers tried to stop the hijackers - trauma therapy has given him strategies for coping with grief. When the pain surged back this week, the retired author tried to remember those strategies on a park bench near his home in Pebble Beach, Calif.

He summoned gratitude for what he’d shared with Lauren, who had been pregnant with their first child when she died. She left him a voicemail in the final, desperate moments: “I just love you more than anything, just know that.”

Nothing could bring her back, but he told himself that a life sentence was, in fact, a terrible destiny. At least the case seemed to be winding at long last toward some kind of conclusion.

What the 61-year-old Grandcolas still hopes for: “To have something happen in my lifetime.”