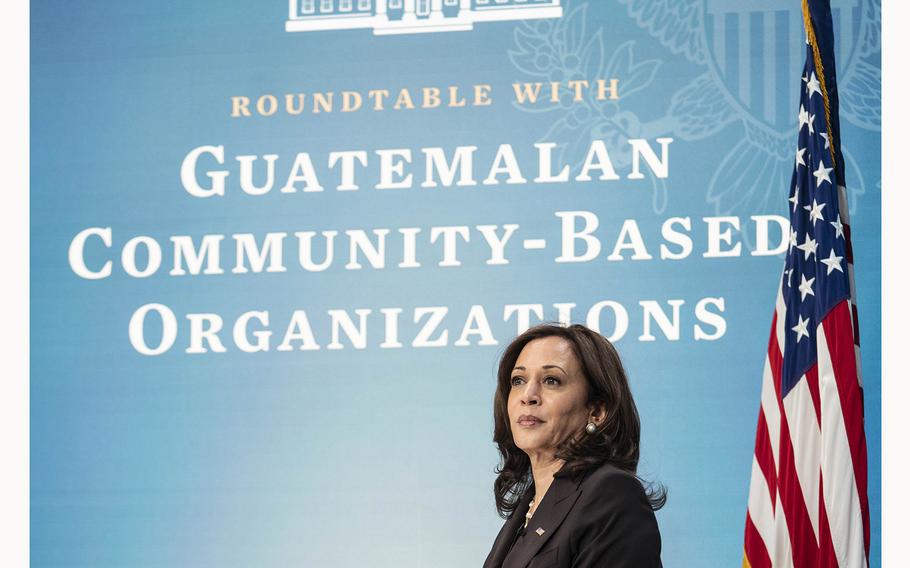

Vice President Kamala Harris listens during a virtual roundtable with representatives from Guatemalan community-based organizations on April 27, 2021. (Sarah Silbiger/Bloomberg)

Kamala Harris’ effort to tackle the root causes of migration is now one of her biggest liabilities as she seeks the presidency.

As vice president she had a broad, if ambitious, mandate to tackle problems contributing to a surge in migration from Central America to the US: Fight corruption; lure investment and strengthen the rule of law. Promote human rights and battle organized crime.

Three years later, there’s little to show for the effort, even if it was never intended to put an immediate halt to emigration. Before President Joe Biden issued an executive order in June to limit asylum claims, resulting in a slowdown in newcomers at the border, arrivals from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador - the three countries known as the Northern Triangle that Harris focused on - had fluctuated, falling in fiscal years 2022 and 2023 before rising in the first few months of this year.

That failure, as critics see it, has dogged Harris since she became her party’s presumptive nominee for president in this year’s election. Polling in swing states by Bloomberg News and Morning Consult has shown immigration is the No. 2 most important issue to voters, behind only the economy. Donald Trump and running mate JD Vance have already sought to hammer Harris on the issue.

“To the extent that the policy was meant to stem migration flows, we still have very significant flows of immigrants from those countries,” said Risa Grais-Targow, director for Latin America at Eurasia Group. Efforts at promoting transparency in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador sometimes strained ties with their leaders, ultimately pushing the administration to prioritize investment rather than the plan’s other objectives, she said.

When Harris was assigned the responsibility in June 2021 amid a jump in emigration from Central America, the idea was to make fundamental fixes to the countries’ civic framework in a bid to make life better and lessen locals’ desire to leave for the US. This would show moderates that the border was a priority, while avoiding upsetting progressives who were horrified at harsh crackdowns during the Trump administration.

Harris’ supporters point out that her mandate was limited to three countries, not a broad remit to fix a broken immigration system. They say her accomplishments were significant, arguing the measures will pay dividends for years to come. Outward migration has declined in locations where the strategy has successfully attracted companies and created jobs, and foreign direct investment has risen in the region due in part to White House efforts to encourage private investments, proponents say.

And they highlight how difficult the job was in the first place: Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador are all developing countries with volatile politics, and Harris backers say critics are naive to suggest decades-old problems like endemic corruption or a lack of judicial transparency could be swiftly and easily solved.

“She managed to mobilize and connect with the private sector,” said Jordi Amaral, a researcher who runs Migration Brief, a newsletter that tracks the subject. “At the end of the day though, the Root Causes Strategy was always a long-term deal - this was never going to slow migration in the short term.”

The White House announced this year that it had cemented $5.2 billion in investment pledges for the region from companies including Meta Platforms, Nestle and Target. That’s equivalent to more than 3% of the countries’ combined gross domestic product.

But participating organizations had deployed only $1 billion as of September 2023, according to a State Department report to Congress.

“In reality, very little has materialized. It was more of an image thing, an expression of political support,” said Paulo de Leon, the director of Guatemala City-based business consultancy Central America Business Intelligence.

The White House acknowledges investment has been slower than initially hoped for. It says the Partnership for Central America has created more than 20,000 jobs, led to 160,000 bank accounts being opened and connected 2 million people to the internet in Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala.

While the Root Causes Strategy included broad efforts to strengthen government integrity and the rule of law, it’s hard to identify specific achievements in that arena.

Last year, the US helped lead efforts to uphold election results in Guatemala following attempts by local prosecutors overturn them. This year, a US delegation visited Guatemala to advise its government on good governance, improving infrastructure and antitrust law. Military officials from US Southern Command visited Honduras last year to discuss security cooperation. The United States Agency for International Development has also launched food and education programs in Central America to reduce malnutrition and keep kids in school.

Those initiatives have yet to yield much in the way of concrete results, and by some measures democracy has actually retreated in the region. El Salvador President Nayib Bukele has used a state of emergency to undertake mass arrests of violent criminals, suspending civil liberties like freedom of assembly in the process. Honduras followed Bukele’s lead when President Xiomara Castro embarked on a similar campaign in late 2022. In Guatemala, President Bernardo Arevalo has pledged to add 12,000 recruits to the country’s police force over the next four years.

“It’s crucial for US government to engage in initiatives that democratize the economies in the region, not just investment,” said Ana Maria Mendez Dardon, Central America director at the human rights research group Washington Office on Latin America.

Perhaps the most successful business initiative fostered under the program involved the auto-parts maker Yazaki North America, which signed Harris’ pledge. In 2023, the firm opened a $10 million factory in northern Guatemala making wiring harnesses used by Ford, General Motors and BMW. The factory hired 1,000 people in its initial stage.

Still, Republicans have hit at Biden, and now Harris, on the more than 8 million recorded crossings between ports of entry since Trump left office. GOP officials have advocated for a border crackdown but have blocked legislative efforts, including this year’s bipartisan Senate proposal, that would have directed new funding to the border.

Their messaging has been effective, according to the latest Bloomberg News/Morning Consult poll of swing-state voters. When asked who they trusted more to handle immigration, 53% of respondents favored Trump, compared with just 37% for Harris.

Harris, the daughter of immigrants, has pushed back in the early days of her presidential campaign, pledging at a rally in Georgia this week to find bipartisan agreement on the US-Mexico border.

“As president, I will bring back the border security bill that Donald Trump killed and I will sign it into law and show Donald Trump what real leadership looks like,” Harris said in Atlanta.

Her campaign has signaled she would allow Biden’s executive order limiting asylum claims to stand. But Harris herself has distanced herself from the policy - she wasn’t at its announcement, didn’t put out a statement and has declined comment this week on whether it will continue.

Trump, for his part, has pledged to lead the largest deportation effort in the nation’s history and redirect local police to aid in border control. He has also vowed to complete the construction of the border wall that he ran on in 2016. A common fixture of his stump speech equates undocumented migrants with criminals and asserts that they are “poisoning the blood” of the country.

One critical question is how much help the next US president will get from Mexico, which has stepped up its own enforcement measures to reduce the number of migrants arriving at the US border. Much of the effort has been concentrated in the south, near Mexico’s border with Guatemala, where authorities bolstered highway checkpoints.

Mexico also rounded up migrants in the north and bused them south, setting back their journeys. Authorities have increased monitoring of freight trains in a bid to prevent migrants from jumping aboard.

President-Elect Claudia Sheinbaum takes power in October, but so far there’s little sign that her approach will be different from her predecessor, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador. In June, she met with White House Homeland Security Adviser Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall and discussed migration among other topics.

For all the effort the US has put forth in Central America, Border Patrol encounters with with citizens of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador were at 29,077 in May, up slightly from when Biden and Harris took office. They dipped to 24,120 in June as Biden’s new restrictions on asylum took effect.

“The US has tried for decades to promote economic prosperity in the region, but unfortunately these efforts have not been successful in preventing irregular migration,” said WOLA’s Mendez Dardon. The prospect of the American dream still enchants people, especially in rural areas, who face limited economic opportunities.

“These measures haven’t had the impact Harris expected because they aren’t necessarily linked with realities in the region,” she said.

With assistance from Josh Wingrove, Stephanie Lai, Maya Averbuch, Sarah Halzack and Robert Jameson.