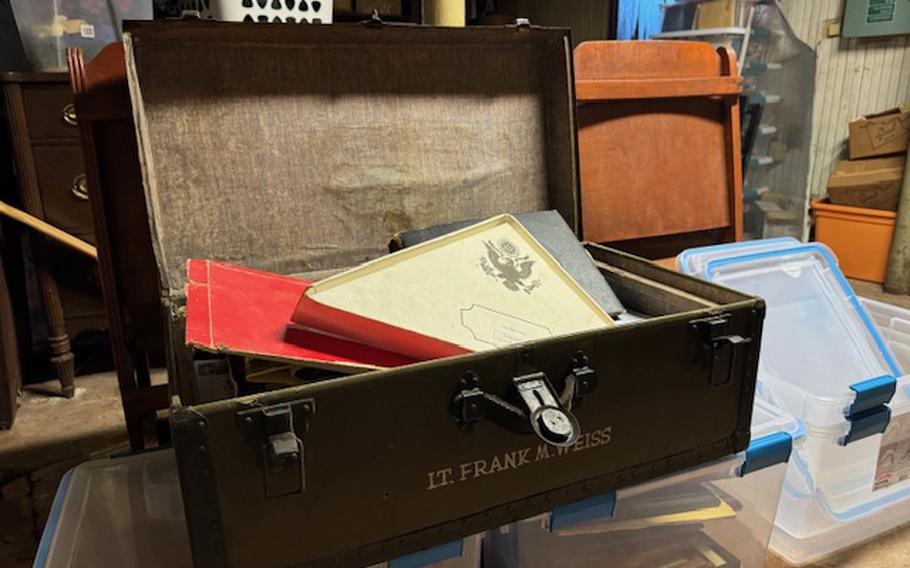

A World War II-era Army Air Forces footlocker bearing the name Lt. Frank M. Weiss sits at the Pawtucket, R.I., home of the late officer’s son Herb Weiss in this recent photo. The trunk was found in April on a curbside in Detroit by Michael Shannon, who found Herb Weis online and gifted him his father’s footlocker. (Photo provided by Herb Weiss)

Herb Weiss did not know the box existed.

But late one April evening, when the 70-year-old Rhode Islander could not sleep, he saw a Facebook message from a stranger. The man, Michael Shannon, had happened upon an old Army trunk that had been discarded on a curb in Detroit for bulk trash collection.

It was in good shape and bore the name, in all capital letters, Lt. Frank M. Weiss — the name of Herb Weiss’ late father and the rank that he wore when he left the Army at the end of World War II.

The olive-drab box measured 31 inches wide by 16 inches deep and 13 inches tall, featured a brown, metal frame and buckles and a leather handle. It had sat — apparently untouched — in a northwest Detroit garage for nearly six decades, Shannon had learned. Weiss wondered: Could this really be his father’s old Army Air Forces footlocker?

“It’s mind-boggling,” Weiss recounted. “My father’s from Detroit. His home was Detroit while he was in the military. Maybe, amazingly, this is his locker.”

Shannon’s girlfriend, Cetaura Bell, used an internet search to connect Herb Weiss to the name on the footlocker that Shannon had grabbed after watching a person wheelbarrow it to the curb on bulk trash collection day. Shannon offered Weiss the box and asked for nothing in exchange. He was just glad the box could end up with the family of its rightful owner instead of in a landfill or another stranger’s home.

“It’s a sentimental thing,” said Shannon, a 55-year-old retiree of Detroit’s wastewater facility. “I have no idea what it is worth. Maybe I could have sold it. More importantly, if there’s a living family member out there, you know, [Lt. Weiss] I think would have wanted this back with his family.”

2nd Lt. Frank Weiss

Frank Weiss rarely spoke of his three years and four months in the Army Air Corps, Herb Weiss said. And Herb and his three siblings — Michelle, Nancy and his twin Jim — never pushed him to share more about his time in the service.

In some ways, Herb Weiss said, the footlocker makes him wish they had before his death in 2003 at the age of 89.

“I think most people view their parents as parents and not people,” said Weiss, who is the deputy director of a senior center in Pawtucket, R.I., and writes a weekly newspaper column on aging issues for Rhode Island’s Pawtucket Times and Woonsocket Call newspapers and RI News Today, a daily digital news site focused on the state. “My father was always my father to me, and not so much a person. I wish I knew him better on a personal level. I wish I knew about his Army days.”

Old military and family documents saved for years — and now safely stored in the footlocker alongside some of Frank Weiss’ other military memorabilia — tell some of the tale of his military career.

Weiss was 27 years old when he was drafted into the Army in May 1942, just three months after marrying the former Sally Weller in their hometown of Detroit. Sally Weiss was the daughter of a prominent criminal defense attorney in the Michigan city, and she had taken a seat on the local draft board after the U.S. entered the war in the wake of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

Some citizens, Herb Weiss recalled his mother sharing, had called for Frank Weiss to be drafted, given his renowned father-in-law and his wife’s position on the board. When his number came up, Sally Weiss delivered his notice herself.

“What a shock I received” at getting the draft notice from his wife, Frank Weiss recalled in a 1992 family newsletter marking the pair’s 50th anniversary. He was quickly shipped off to the Army Air Forces as a private.

Herb Weiss, a writer and senior center deputy director in Pawtucket, R.I., received a World War II Army trunk from a stranger who found it in Detroit and linked it via the internet to Weiss’ late father, Army Air Corps 2nd Lt. Frank M. Weiss. (Photo provided by Herb Weiss)

Weiss rose from a private to a technical sergeant in 13 months and was sent off to Miami Beach Officer Candidate School in early 1944, his service records show.

While more than 12 million American troops shipped off to faraway lands to fight in the European, Pacific and North African theatres during World War II, Frank Weiss was among the roughly 27% of U.S. service members during the war who remained stateside, according to figures from the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. Weiss would spend the war moving from one base to another working as a clerk and then a chief clerk before training to become an administrative officer in Florida.

He served at Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis with the 357th Technical School Squadron and at the 1033rd Technical Squadron at Kearns Army Air Base in Utah. The Army Air Forces sent him to Fresno, Calif., then Harvard University in Massachusetts to study statistics and later the brand-new Meteorology Training Detachment No. 11 at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, where as a staff sergeant he helped build the unit’s headquarters in 1943 as its senior enlisted soldier, according to records provided by Herb Weiss.

At nearly every stop, his commanding officers wrote recommendations that Frank Weiss attend OCS.

Weiss was “a soldier in every sense of the meaning of the word,” one of his commanding officers wrote in 1942.

He “performed his duties with particular excellence and attention to detail,” the commander of the Meteorology Training Detachment No. 11, Maj. Martin W. Krause, wrote in an evaluation the next year. “I have found him to be loyal, competent and efficient. He is commended to the attention of anyone concerned as a superior soldier and of excellent character.”

In March 1944, as tens of thousands of American troops prepared for the D-Day invasion of Europe earmarked for June, Weiss accepted a commission as a second lieutenant, and shipped off days later to Denver, Colo., to work at the Air Corps’ Western Technical Training Command at Lowry Field, where the service was rapidly training as many weapons, aircraft, communications and aerial photography specialists as it could, according to military records.

In August 1945, after Germany’s defeat and as the Japanese neared surrender, Lt. Weiss was given a choice to remain an Army Air Corps officer or accept an honorable discharge.

“I chose to return to Detroit,” Frank Weiss wrote in the 1992 newsletter. He retired his uniform and returned to his job as a merchandise manager at Winkelman’s department store.

Perhaps, Herb Weiss pondered, his father loaded up that Army footlocker and shipped it home to Detroit before he left Denver for military out-processing at Fort Sheridan, Ill., just north of Chicago. In fact, a faded shipping label on the box bears the address of the Wildemere Avenue home in Detroit where Sally Weiss’ parents lived for nearly 30 years. The label convinced Herb Weiss; the box most certainly belonged to his father.

A World War II-era Army Air Forces footlocker bearing the name Lt. Frank M. Weiss sits at the Pawtucket, R.I., home of the late officer’s son Herb Weiss in this recent photo. The trunk was found in April on a curbside in Detroit by Michael Shannon, who found Herb Weis online and gifted him his father’s footlocker. (Photo provided by Herb Weiss)

A mystery

What remains unclear is how Frank Weiss’ footlocker ended up at the home where Shannon saved it from the curb and likely the landfill.

Herb Weiss enlisted the help of a Detroit public librarian and combed city records to see whether he could establish some connection between the family and the Sorrento Street house where the trunk ended up. Shannon asked questions of the homeowners and neighbors, but no one seemed to have any answers about how the trunk ended up in the home some 3.4 miles from the home of Frank Weiss’ in-laws.

“It’s just a mystery,” Shannon said. “I went over there a couple times, and I can’t find out. Apparently, [the homeowner] is elderly, and the trunk’s always been there. They don’t know how. I’m just so curious: How did that trunk get over there?”

He and Herb Weiss said they would continue their efforts to solve that mystery.

Frank Weiss left Detroit for Saginaw, Mich., in the early 1950s after a transfer with Winkelman’s. Ultimately, he ended up in Dallas, where Herb and Jim Weiss were born. Herb Weiss wonders whether his father left the footlocker behind with his in-laws when he moved. Perhaps, he said, his late grandmother sold the box to the owners of the Sorrento Street house when she left Detroit to join her family in Dallas in the 1960s.

He may never find the answer, he acknowledged. But he is eternally grateful for the act of kindness from Shannon and Bell that reunited his father’s footlocker with the Weiss family.

“They did not have to do this,” Herb Weiss said. “He could have sold it, probably made a couple hundred dollars.”

Similar trunks sell online for $200 to $400. Weiss sent the couple a gift certificate to their favorite restaurant as restitution.

For Shannon and Bell, hearing the happiness in Herb Weiss’ voice when they chat with him about the box is payment enough.

Bell found a column that Herb Weiss had penned in November on aging World War II veterans, which he had dedicated to his father, 2nd Lt. Frank M. Weiss. She found no other solid matches for the name on the box.

“You had a very clear name on it, and it just stood out, so I Googled it,” Bell said. “You know, we just wanted the right person to have it, or at least we hoped maybe we could figure out who it had belonged to.”

Once they found Herb Weiss’ columns, she said, “All the pieces of the puzzle really aligned nicely.”

“Luckily, he’s a writer and had done that story, and we were able to find it,” Shannon said.

For Weiss, receiving his father’s World War II footlocker from a stranger who just happened to be in the right place at the right time to grab it, and then tracked him down was like “winning a million-dollar lottery.”

“It’s just something that doesn’t happen often. Absolutely amazing,” Weiss said. “And it was just like amazing on a metaphysical, spiritual level. I said, ‘Man, my father must want to send me a message.’ I’ve got to try to figure out what is the message he wants me to get.”