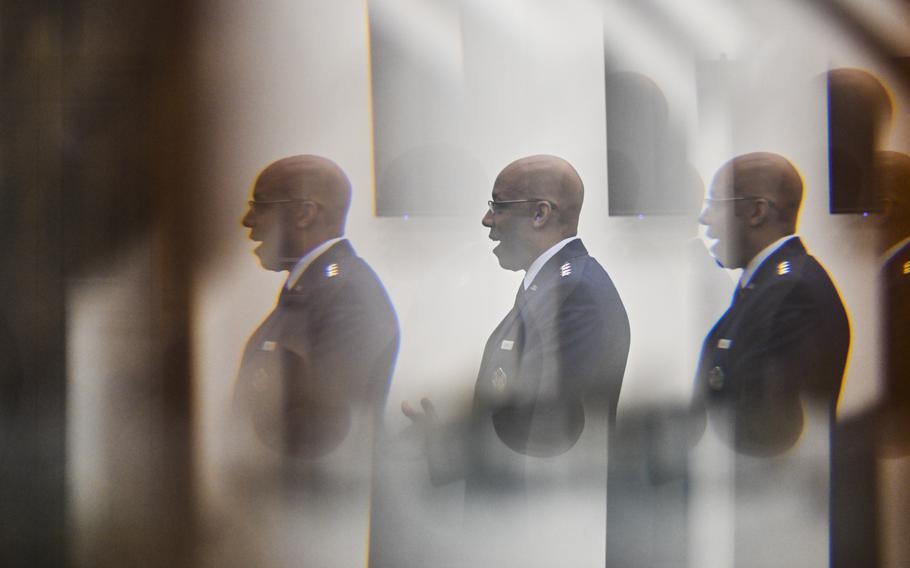

Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr., chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, at the Pentagon in May. (Ricky Carioti/Washington Post)

When Charles Q. Brown Jr. took command of U.S. air forces in the Middle East, the campaign against the Islamic State was moving slowly. It was 2015, and millions of people remained trapped in the militant group’s brutal grip as U.S. and partner forces struggled to chip away at its vast pseudo-state.

Brown, then a three-star general, thought it was time to refocus away from the war’s front lines, where scattered airstrikes were picking off only small numbers of militants. Instead, he wanted to prioritize targets deep within the caliphate, where oil sales and taxation fueled the extremists’ reign.

“If you want us to be more effective, here’s what we’ve got to be able to do,” he recalled telling the Army general commanding the campaign.

Military commanders saw the shift as a turning point, one that led to the liberation of the Islamic State’s twin capitals, Mosul in Iraq and Raqqa in neighboring Syria. Yet it also coincided with a push by U.S. and partner forces into crowded cities, resulting in a soaring number of civilian deaths and revealing a stark reality about the limitations of precision weapons and military safeguards.

Now, as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff - the nation’s highest-ranking military officer - Brown is a key figure guiding America’s support of Israel as it battles Hamas militants in Gaza, where eight months of war have wrought staggering destruction and exposed deep divisions between the two longtime allies over Israel’s overwhelming use of force. Palestinian authorities say at least 36,000 people, most of them civilians, have died since Hamas’s bloody Oct. 7 attacks in Israel ignited the violence. More than 1 million others face famine.

Those tensions were visible again in recent days after an Israeli strike killed dozens of people sheltering in a Gaza school.

Like President Biden’s defense secretary, retired Army Gen. Lloyd Austin, Brown brings to the moment an extensive record overseeing counterinsurgent wars in environments similar to Gaza. Those experiences have both familiarized the men - the Pentagon’s top two leaders - with the challenges inherent to urban combat and informed the Biden administration’s dissatisfaction with Israel’s handling of its war.

Brown and other top officials have cited American operations in places like Mosul, where they believe the United States held itself to a higher standard than Israel is using in Gaza, as they voice frustration with Israel. But while the death toll of the U.S.-led campaign against the Islamic State was smaller relative to Gaza, experts say the Pentagon was dogged by some of the same problems, including a failure to acknowledge civilian deaths when they occurred.

“I hear Western politicians shaking their fists at Israel, and I wonder if they have an understanding of how their own forces have fought,” said Chris Woods, founder of the watchdog group Airwars. “It’s far easier to point at others than take a proper look at your own actions.”

Brown, in an interview at the Pentagon, said he has repeatedly urged Israel to exercise greater restraint, though he acknowledged possessing limited insight about its procedures for balancing military advantage and civilian harm.

For Brown and other leaders, navigating the Gaza conflict is one of their most challenging assignments: Israel, surrounded by historical adversaries, is the United States’ closest ally in the Middle East, and President Biden has staked his political future on defending the Jewish state. At the same time, debate has intensified over U.S. military aid to Israel, which critics allege has enabled the carnage and, potentially, Israeli war crimes.

Asked if Israel was failing to uphold U.S. principles, Brown gave a careful response.

“Not everybody can follow our example,” he said. “But we hold ourselves to a standard, and … those that we work with, we want to help them achieve those same standards to the best of their abilities.”

Dismantling ISIS

In 2014, after the Islamic State surged out of Syria and seized a third of Iraq, President Barack Obama directed the Pentagon to dismantle the group’s so-called caliphate - a mission that faced immediate obstacles.

Iraqi forces, which Washington was helping to rebuild following an embarrassing collapse, encountered punishing opposition as they attempted to liberate the smaller cities of Ramadi and Baiji. Ideally, U.S. airstrikes would have helped weaken the enemy before Iraqi units plunged in, using what military officials call “shaping” operations. That had yet to happen.

“It was a knife fight,” said Sean MacFarland, the Army general then commanding the war. “It was eyeball to eyeball, and there was no shaping, no deep fight, no attrition of enemy forces out of contact whatsoever.”

MacFarland said Brown, a former F-16 pilot who goes by C.Q., suggested they rebalance the air campaign, which then consisted mostly of attacks responding to skirmishes involving partner forces and small numbers of militants. Instead, the coalition could target arms factories, banks or oil rigs, whose destruction would do more to erode the Islamic State’s power.

That shift was one of the consequential changes during Brown’s tenure overseeing the Islamic State campaign. Another was a gradual loosening of regulations governing coalition strikes, which military officials said was needed to kill more militants but which many experts believe contributed to a spiraling death toll during its final battles.

When the war against the Islamic State erupted, the Obama administration already was under pressure to rein in the civilian toll generated by America’s ongoing counterterrorism wars, by then more than a decade old. In 2015, Obama publicly apologized after a drone strike killed an American held hostage by al-Qaeda in Pakistan. In 2016, the White House issued an order committing to exceed civilian-protection requirements set out in the laws of war.

Against the Islamic State, the administration initially granted only a handful of high-ranking ground commanders the ability to authorize airstrikes, and set to zero the number of civilian casualties a strike could be expected to generate without seeking higher approval.

While ground commanders said they shared the goal of minimizing civilian harm, they chafed at restrictions imposed by higher headquarters, rules they believed would make it harder to defeat the militants.

Brown, MacFarland and others thought that without embracing greater risk in the air campaign, the coalition would be unable to take out key Islamic State infrastructure.

Eventually, after repeated appeals, military leaders eased those constraints. Suddenly, an array of new targets was fair game.

Take extra precautions

By early 2016, all airdropped arms used against the Islamic State relied on guidance technology, Brown said at the time. He called it “the most precise air campaign in history.”

To minimize unintended harm, U.S. pilots dropped bombs with lower yields and employed delayed fuses. Throughout the war, the coalition struck hospitals and mosques a handful of times.

Brown supported the changes, but he said the loosening of rules in the Islamic State war required military commanders to take extra precautions to mitigate tragedy, as he has urged Israel to do.

“Our goal still was to get to zero” civilian casualties on any given strike, he said.

Brown also cited the importance in urban battles such as in Gaza of moving civilians out of harm’s way, which the coalition did with mixed success before the battle for Mosul in 2016-2017. In some cases, those residents were able to flee and reach United Nations refugee camps. In others, Iraqi authorities urged residents to stay put, or militants prevented them from leaving. When the coalition turned to Raqqa, tens of thousands of residents were trapped as militants made their final stand.

“When you get into an urban environment … it’s a bit more challenging, but you still try to take every effort,” Brown added.

‘We weren’t perfect’

Nevertheless, the peril facing remaining residents skyrocketed. According to Airwars, at least 1,300 civilians probably died in Mosul because of coalition actions in the city, and at least 1,600 in Raqqa.

Overall, Airwars found that coalition strikes probably killed at least 8,000 civilians over nine years, far more than the roughly 1,300 acknowledged by the Pentagon. Experts said mistaking civilians for legitimate targets and other intelligence problems, like elsewhere, were primary drivers of civilian deaths.

Most military officials saw the bloodshed as a lamentable inevitability when battling an enemy that wove itself into the populace and used civilians as human shields, as Israel has accused Hamas of doing.

Scott Efflandt, who spent hundreds of hours watching drone footage when he led a strike cell during the Mosul operation, said he saw militants holding babies above their heads as they dashed between buildings, knowing coalition aircraft were unlikely to fire. He recalled the aftermath of one botched strike in Mosul, when U.S. forces hit a building where roughly 100 civilians were sheltering, hidden from view. All died.

“It just weighs on your soul when you’re done, but what are you going to do?” Efflandt said. “There’s no perfect solution for this.”

Those experiences, and the public pressure they generated, led to new steps to prevent such loss of life. In 2017, the Pentagon commissioned a study to scrutinize its track record on civilian casualties. A plan to embed new practices across the military was approved in 2022.

Woods, of Airwars, said the United States had done far more to acknowledge harm and institutionalize lessons learned than its coalition partners had. Britain, he noted, has acknowledged just one civilian death in the Islamic State campaign.

For Brown, the experience underscored the importance of preventing conflict to begin with.

“We want to be so good at what we do that our adversaries never want to go to conflict with the United States,” he said. “But if they do, we’re going to have capability to take out the enemy, but we’re also going to have the capability to protect the civilians. We’ve got to be able to do both.”

‘How we do things’

When Brown received a call before dawn on Oct. 7 alerting him of the Hamas assault in Israel, he had been Joint Chiefs chairman for a week.

Washington’s message was clear: The United States would back Israel’s response to the attacks, in which Hamas killed 1,200 people and took more than 250 hostages.

But officials soon grew dismayed as they watched the humanitarian crisis and death toll mount, quickly surpassing the scale of the Islamic State war.

Through the Gaza war’s first seven months, Airwars has identified more than 4,500 attacks that it suspects are responsible for civilian death or injury, though work to verify those figures is ongoing. The group identified about 3,000 incidents for the entire Islamic State campaign.

According to an analysis by Larry Lewis of CNA, a research firm, Israel as of late February appeared to have killed an average of 54 civilians per 100 attacks. The ratio in Raqqa, by comparison, was 1.7 civilian deaths per 100 attacks based on Pentagon casualty estimates, or seven deaths based on Airwars data.

While a recent administration report found that it was “reasonable to assess” that Israel has violated global laws using U.S. weapons, Biden’s reaction has fallen far short of critics’ demands; he has paused just one shipment of large bombs as he urges Israel to forgo a full-scale offensive in the southern city of Rafah.

The response “has entirely failed to live up to - and actually undermined - the civilian protection efforts the U.S. has made in recent years,” said Annie Shiel, U.S. policy director of the Center for Civilians in Conflict, calling on the Pentagon to “unequivocally reject Israel’s conduct.”

U.S. defense officials say that Israel briefed them on the precautions its forces take to minimize civilian harm - including legal reviews, proportionality tests and, when possible, advance warning to those in danger - and that Israel’s system resembles their own. Why those safeguards have not prevented the staggering loss of life is unclear, they say.

While Brown acknowledged having a broad understanding of Israel’s process for mitigating civilian casualties, when pressed he said he lacked information about whether Israeli forces use a casualty cutoff, as the U.S. military does, or how they approach proportionality. And like other U.S. officials, he pointed out Hamas’s practice of embedding in schools and other protected sites.

Retired Gen. Joseph Votel, who led U.S. Central Command when Brown served as the deputy commander there, said he wonders about the tone set by leaders in Israel, where early in the war Defense Minister Yoav Gallant cited the battle against “human animals,” and some members of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s cabinet continue to urge the “complete destruction” of Gaza.

U.S. leaders, at the outset of the Islamic State war, telegraphed the importance of keeping noncombatants safe, Votel said. He recalled flying in a B-52 bomber over Syria and observing how pilots felt empowered to call off a planned strike if they detected something amiss.

“That’s the kind of thing that C.Q. put in place,” Votel said. “It’s not flashy, but it goes back to this idea of tone about how we do things, and [saying], ‘If it doesn’t look right, then don’t do it.’”