U.S.

AnalysisHarvard, Columbia say no to students demanding Israel divestment

Bloomberg April 26, 2024

Pro-Palestinian signage at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. (Joe Buglewicz/Bloomberg)

A cause celebre is ringing out across Harvard Yard, Columbia’s South Lawn, Yale’s Beinecke Plaza and UC Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza: Disclose and divest.

And university students say they won’t stop protesting against Israel until that demand is met.

“We’re willing to risk suspension, expulsion and arrest, and I think that that will put pressure,” said Malak Afaneh, a law student at University of California, Berkeley, and a protest organizer.

She and her fellow pro-Palestinian demonstrators want universities to cut their investments in everything tied to Israel and weapons that fuel the war in Gaza. That means funds run by BlackRock, Google as well as Amazon’s cloud service, Lockheed Martin and even Airbnb.

It’s a long-shot demand - university administrators and lawmakers have for decades rejected the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement against Israel, viewing it as antisemitic because it calls into question the legitimacy of the Jewish state and singles out the policies of one country.

What’s more, acting on the BDS concept is discouraged by laws in more than half of US states, including New York and California, and is fiercely opposed by many donors and alumni.

Yet it’s gaining proponents, especially among students at elite universities since Oct. 7, when Hamas attacked Israel and sparked the conflict in Gaza that has killed tens of thousands of Palestinians.

They’re chanting on college grounds, waving Palestinian flags, wearing keffiyehs and beating drums. Encampments have sprouted on campuses, including at Harvard where about 30 tents currently stand in front of the John Harvard statue, according to the Harvard Crimson.

Some protesters, including at Columbia and Berkeley, have threatened Jewish students and expressed support for Hamas, which is designated a terrorist organization by the US.

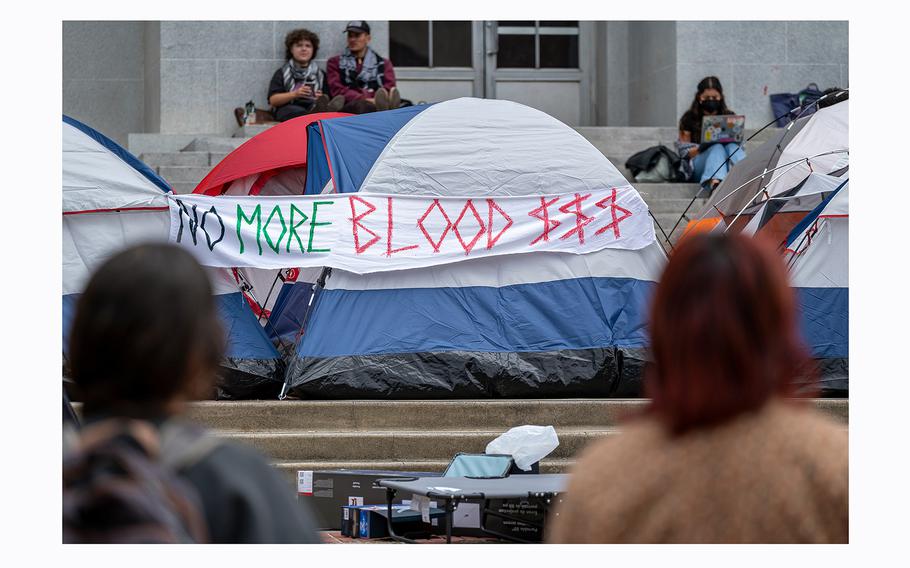

Pro-Palestinian demonstrators at an encampment on the University of California, Berkeley. ( David Paul Morris/Bloomberg)

All that has left universities struggling to balance the right to free speech with the need for maintaining order and ensuring the safety of students. But on the question of divestment, they are unmoved.

Harvard, which has the largest US endowment at almost $51 billion, made clear this month it “opposes calls for a policy of boycotting Israel and its academic institutions.” Brown refused to acknowledge BDS demands while students led an eight-day hunger strike. Yale this week wouldn’t even consider a proposal to divest from weapons makers and instead police rounded up protesters outside of the Schwarzman Center, arresting more than 40 students.

BDS supporters take inspiration from the drive to isolate South Africa during the apartheid era - including actions taken at the time by Columbia, Michigan State and California universities - and recent pushes for colleges to address fossil fuel holdings.

This time at Michigan State, where groups of students are camped in tents in People’s Park, there’s no appetite for severing ties with Israel.

“Divestment would conflict with stewarding the institution’s financial health, would increase investment risks, and limit returns and jeopardize the assurance resources will continue to be available now and for future generations,” said Sandy Pierce, chair of Michigan State University’s board, speaking earlier this month at a Board of Trustees meeting.

Columbia in February declined a proposal to withdraw financial support from Israel, months before students set up tents on the Morningside Heights campus and created a standoff with the university that resulted in more than 100 arrests.

Ray Guerrero, 27, who’s studying for a masters in public health, helped pen the divestment proposal for the Columbia University Apartheid Divest coalition. The group has a litany of demands, including cutting ties to Israeli academic institutions, defunding public safety and reparations for the indigenous people of New York. Guerrero understands the goals are lofty for the immediate term, but stresses the main focus for now is disclosure and divestment around Columbia’s $13.6 billion endowment.

Layla Saliba, a 24-year-old studying for a masters in social work, is part of CUAD’s research team, which she said has been studying the school’s financial disclosures, including its tax forms and 13Fs disclosures to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

“We were only able to get about 0.6% of their investments as public information,” she said.

The latest 13F discloses just $47 million of its holdings, with the vast majority stock in Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. That leaves billions of dollars undisclosed.

“That’s really concerning because our endowment, yes, it’s funded by benefactors, it’s funded by donors, but a portion of that is also funded with our tuition dollars,” Saliba said. “And we feel that as students, we need to have more transparency on that.”

Demonstrators stand off with police officers during a pro-Palestinian protest at the University of Texas in Austin. (Jordan Vonderhaar/Bloomberg)

Universities say the protesters’ claims aren’t accurate.

College endowments are almost always funded with donations and investment gains, not necessarily tuition revenue. What’s more, they fund financial aid for students and other operating expenses such as teacher salaries.

And the challenge isn’t just ideological. Endowments typically don’t hold large concentrations of single stocks as they used to decades ago, when activists targeted companies operating in South Africa.

Endowments have long relied on external managers, including private equity firms and hedge funds. Almost 700 institutions hold about $840 billion in endowment assets. They also use ETFs, index funds or mutual funds that pool hundreds of stocks and bonds.

With private equity, a school’s money may be locked up for several years, without an option to withdraw, while hedge fund managers can rapidly move in and out of securities without disclosing their trades to investors.

“These active strategies are not buying stocks to hold on for the long term,” said Philip Zecher, chief investment officer of Michigan State University’s $4 billion fund. “They’re looking to make money off trading. It’s not like your grandmother buying AT&T stock and sitting on it for 50 years.”

The fight against fossil fuel investment, a cause championed by students for decades, also shows how hard it can be to implement divestment. Universities largely haven’t switched strategies to sell holdings, which are frequently tied up in long-term private equity funds, even as they’ve committed to policies designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions on campuses.

Despite the setbacks and opposition, some pro-Palestine protesters are undeterred.

“It seems like a no for now, but students will keep pushing,” said Lumisa Bista, a junior studying astrophysics at Yale, who was among protesters at the university who slept overnight at Beinecke Plaza this week. “I’ll keep pushing.”

With assistance from Maxwell Adler, Shelby Knowles and Brendan Case.