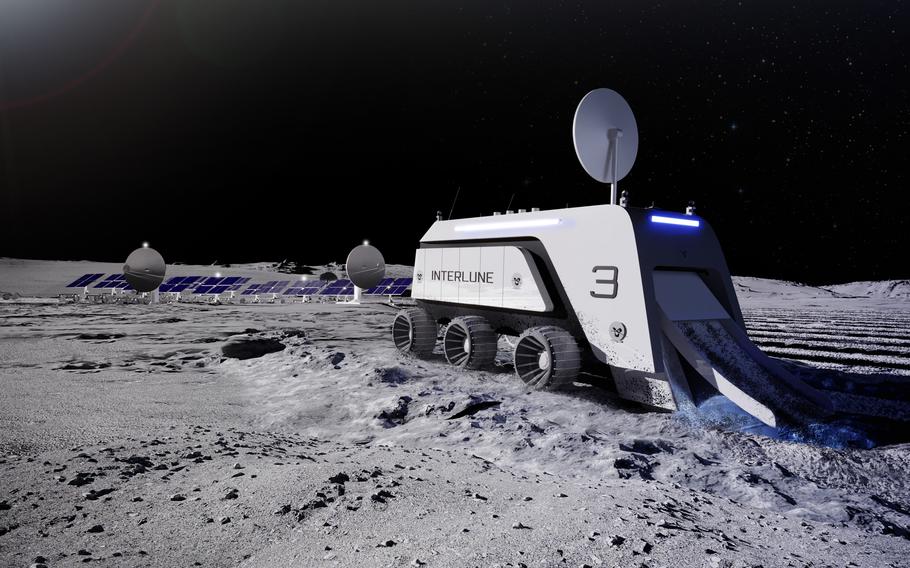

An artist’s rendering shows what Interlune’s Helium-3 harvester might look like on the surface of the moon. The company hopes to become the first private venture to extract resources from the lunar surface and return them to Earth. (Interlune)

Nearly a decade ago, Congress passed a law that allows private American space companies the rights to resources they mine on celestial bodies, including the moon.

Now, there’s a private venture that says it intends to do just that.

Founded by a pair of former executives from Blue Origin, the space venture founded by Jeff Bezos, and an Apollo astronaut, the company, Interlune, announced itself publicly Wednesday by saying it has raised $18 million and is developing the technology to harvest and bring materials back from the moon. (Bezos owns The Washington Post.)

Specifically, Interlune is focused on Helium-3, a stable isotope that is scarce on Earth but plentiful on the moon and could be used as fuel in nuclear fusion reactors as well as helping power the quantum computing industry. The company, based in Seattle, has been working for about four years on the technology, which comes as the commercial sector is working with NASA on its goal of building an enduring presence on and around the moon.

Earlier this year, two commercial spacecraft attempted to land on the moon as part of a NASA program designed to carry instruments and experiments to the lunar surface, and eventually cargo and rovers. The first attempt, by Astrobotic, a Pittsburgh-based company, suffered a fuel leak and never made it to the moon. The second, by Houston-based Intuitive machines, did land on the moon, but came in too fast and tipped over. Still, it was the first American spacecraft to land softly on the moon in more than 50 years, and it was the first commercial vehicle to achieve the feat.

NASA is planning additional missions in the year to come, which it says will not only help pave the way for humans to return to the moon but for private industry to begin commercial operations there as well.

Rob Meyerson, the former president of Blue Origin, co-founded Interlune with Gary Lai, another former executive at Blue, and Harrison Schmitt, a geologist who flew to the moon during Apollo 17. Also on the founding team are space industry executives Indra Hornsby and James Antifaev.

In an interview, Meyerson said that the company intends to be the first to collect, return and then sell lunar resources and test the 2015 law. There is a large demand for Helium-3 in the quantum computing industry, which requires some of its systems to operate in extremely cold temperatures, and Interlune has already lined up a “customer that wants to buy lunar resources in large quantities,” he said.

“We intend to be the first to go commercialize and deliver and support those customers,” he said.

NASA might want to be a customer as well. In 2020, it said it was looking for companies to collect rocks and dirt from the lunar surface and sell them to NASA as part of a technology development program that would eventually help astronauts “live off the land.”

In a tweet, then-NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine wrote that the agency wanted “to establish the regulatory certainty to extract and trade space resources.”

NASA has also said it is in a space race to the moon with China. Both are focused on the lunar south pole, where there is water in the form of ice in the permanently shadowed craters there. But China has also said that it is interested in extracting other resources, including Helium-3, which it said was present in a sample it returned from the moon in 2020.

Interlune intends to conduct a prospecting mission as early as 2026, when it would fly its harvester on a commercial rocket and spacecraft to an area of the moon believed to hold vast quantities of Helium-3. Once there, it would dig through the lunar soil, or regolith, as it is known, and using a spectrometer measure the amount of Helium-3 it collected. “The objective there is to get the data,” Lai said in an interview.

If that goes as planned, the company hopes to launch another mission in 2028 that would be an “end-to-end demonstration of the entire operation,” Lai said. That would entail flying a harvester to the moon, which would scoop up the regolith, then its processor would separate out the Helium-3. A small quantity would return to and be put “into the hands of the customer.” By 2030, the company intends to conduct full-scale operations.

But getting to the moon is difficult — and expensive. Setting up a mining operation and then bringing the products home is even more so. To be successful, Interlune would have to rely on a number of launches and technologies that don’t yet exist, such as a lunar rover that would crisscross the surface to dig up regolith.

But Meyerson said Interlune has a chance of being successful because of the growing demand for Helium-3 and advances in space transportation and technology over the last several years.

Interlune has developed an extraction technology that is small, light and doesn’t require an enormous amount of power, he said, making it easier to transport to the moon and operate there.

The company is also betting that as more commercial space ventures begin flying to the moon in partnership with NASA, deliveries to and from the surface will become more common, the way SpaceX now flies crew and cargo to the International Space Station in low earth orbit.

“We’re just starting this operational cadence, and we’re really building the whole industrial base around going to the moon,” Meyerson said.

The company’s funding round was led by the venture capital firm Seven Seven Six, whose founder and general partner, Alexis Ohanian, said that the space sector has become far more appealing to investors. “The space economy is something we can actually talk about with a straight face now, and I think some of the smartest people on the planet are making those efforts,” he said.

That’s in large part, he said, because of companies like SpaceX, which is flying its reusable Falcon 9 rocket at an unprecedented rate and is working on its next-generation Starship rocket, which NASA intends to use to carry astronauts to the moon.

“We’ve seen the technology come such a long way,” Ohanian said. “Obviously, what SpaceX has done has really validated the potential for what private companies can do in this space and really shown a tremendous business model. And that, frankly, opens the door for funds like ours to say, ‘Yeah, why not?’ We’re not exclusively investing in space, but we feel like it makes sense to take these really ambitious bets on technology that can potentially drive tremendous, tremendous value. And while it’s risky, we have a great appetite for that.”

He said he was aware that it might take years, or longer for a moon mining business to make money. But he said that, “we’re comfortable waiting for a decade plus to see those returns.”