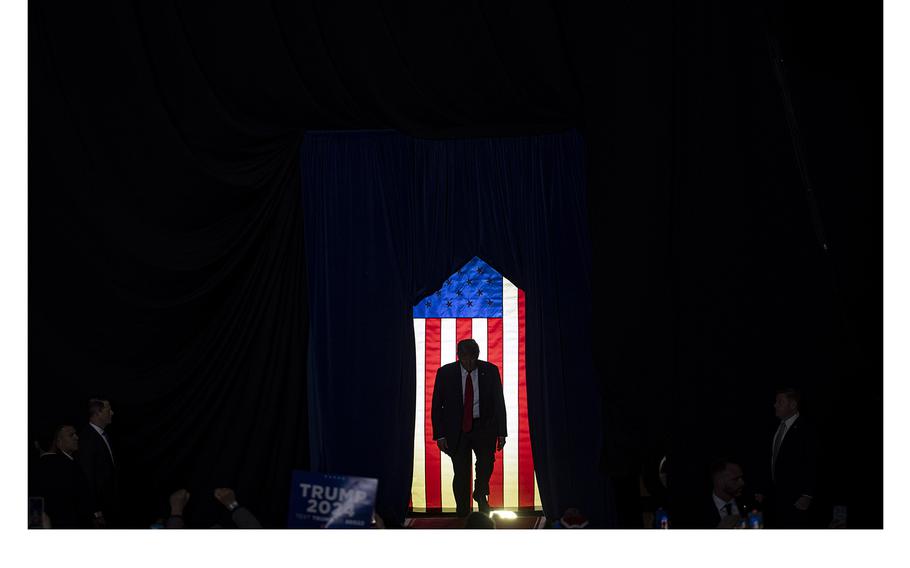

Former President Donald Trump on Jan. 20, 2024. (Al Drago/Bloomberg)

A historic showdown over Donald Trump’s eligibility to reclaim the White House puts pressure on the US Supreme Court to provide a clear political road map as the nation braces for the prospect of a tumultuous year.

Thrust into the fray by a Colorado ruling that barred Trump from this year’s presidential ballot because of his efforts to overturn the 2020 election, the high court will tackle novel questions about the Constitution’s insurrection clause, while trying to minimize its own ideological divisions.

The court hears arguments Thursday amid warnings that a misstep might mean a fragmented, chaotic election in a country still reeling from the Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol riot. A ruling against Trump would mean other states could bar him, something he told the justices would “unleash chaos and bedlam.” And a group of ideologically diverse election-law experts said anything short of a definitive ruling on Trump’s eligibility risked fostering a “catastrophic” constitutional crisis and violence.

“Not since the Civil War has the United States confronted such a risk of destabilizing political unrest, and perhaps never has this Court been in such a clear position to head it off,” said election law scholars Edward Foley and Rick Hasen and retired Republican election lawyer Benjamin Ginsberg in a court filing that was among dozens submitted before Thursday’s special session.

Their warnings underscore the stakes in the most consequential presidential election case since the 5-4 Bush v. Gore decision ended the 2000 deadlock and dealt a blow to the court’s reputation. The clash promises to not only be a pivot point in the rematch between Trump and Joe Biden, but also a test of whether Chief Justice John Roberts can avert a bitter split on a court whose conservative supermajority includes three of the former president’s appointees.

The court for the first time will interpret the post-Civil War 14th Amendment provision that bars people who took an oath to support the Constitution from holding office again if they “engage in insurrection.” Options include an outright Trump victory, a punt to Congress and a decision that lets states bar him from the ballot. Each approach has its advantages and its pitfalls.

A Trump triumph

Trump’s attorney Jonathan Mitchell said in a reply brief filed Monday that the Colorado court is an “outlier” and asked the justices to reverse the ruling “and protect the rights of the tens of millions of Americans who wish to vote for President Trump.”

Trump has multiple ways to win, including two paths that would effectively end the efforts to bar him.

The primary focus of an earlier brief filed on Jan. 18 is that the president isn’t covered by the insurrection clause, which applies to anyone who was an “officer of the United States.” Trump’s lawyers say the phrase is a legal term of art that elsewhere in the Constitution excludes the president.

The argument “gives the court a way to rule for Trump and for Trump to claim victory without the court having to weigh in on the insurrection or his conduct,” said Hasen, a UCLA School of Law professor.

But both Hasen and Stanford Law School professor Michael McConnell, said a ruling on those grounds would risk sounding “hyper-technical.” Added McConnell, a former federal appeals court judge, “I think they will want to decide the case on a basis that the American public will find potentially persuasive.”

Trump also argues he didn’t “engage in” insurrection. In concluding he did, the Colorado Supreme Court pointed to his unsupported claims of a stolen election, his fiery Jan. 6 speech and his demands that Vice President Mike Pence refuse to certify the results.

Several legal experts said Trump has a legitimate argument that his actions didn’t cross the line separating political protest from insurrection. At the same time, the justices might be wary of trying to assess Trump’s blame when he is under indictment in Washington and Georgia over his efforts to overturn the election results.

“Frankly, I think that’s one of his stronger arguments,” said Derek Muller, a University of Notre Dame election-law professor. “But that also requires the court to get into the weeds of the events of Jan. 6 and Trump’s state of mind when tweeting, which I think the court wants to avoid.”

Passing the buck

Two other arguments would kick the issue to Congress. Trump contends Congress must set up an enforcement system before the insurrection clause can be used. He also says the provision bars people only from holding office, not from running for it.

Both approaches would let the court avoid being the final arbiter on Trump’s eligibility and might offer a path for consensus.

But they would also risk the specter of a Trump victory in November followed by a congressional effort to stop him from taking office. The nation might again face a volatile showdown when Congress counts the electoral votes on Jan. 6.

And deferring to Congress would risk disenfranchising 70 or 80 million people, said Ginsberg, the retired Republican election lawyer. “That seems not to be right because you ought to be able to tell people beforehand if the person they vote for would be eligible,” Ginsberg said.

Ousting Trump

A ruling against Trump would carry risks. It would keep him off the ballot this year in Colorado and potentially in Maine, where the state’s top elections official has moved to block Trump. Other states might follow, and litigation is already underway in several.

But it wouldn’t necessarily keep Trump off enough state ballots to prevent him from winning election. A Trump victory in November would put Congress in the position of deciding whether to count his electoral votes even though the Supreme Court had declared him ineligible.

Some experts doubt those head-spinning possibilities will happen. Foley, who runs the election law program at Ohio State University’s Moritz College of Law, said the chances are “fairly low” for a ruling that disqualifies Trump given the multiple ways he can win.

Other paths

Trump’s appeal also makes a Colorado-specific argument that the state court ignored its own election laws to such an extent it violated the US Constitution.

And the Colorado Republican Party says political parties have a First Amendment right to select their nominees. If the court wants a narrow ruling, it could apply that reasoning only to the primary, leaving Trump’s general election eligibility unresolved.

Whatever the court does, it should provide a clear resolution, even at the cost of its public standing, Foley says.

“If it turns out that there’s a tension between the court’s reputation versus what’s good for the country,” he said, “I’d rather the court take a hit to its reputation for the sake of the country.”