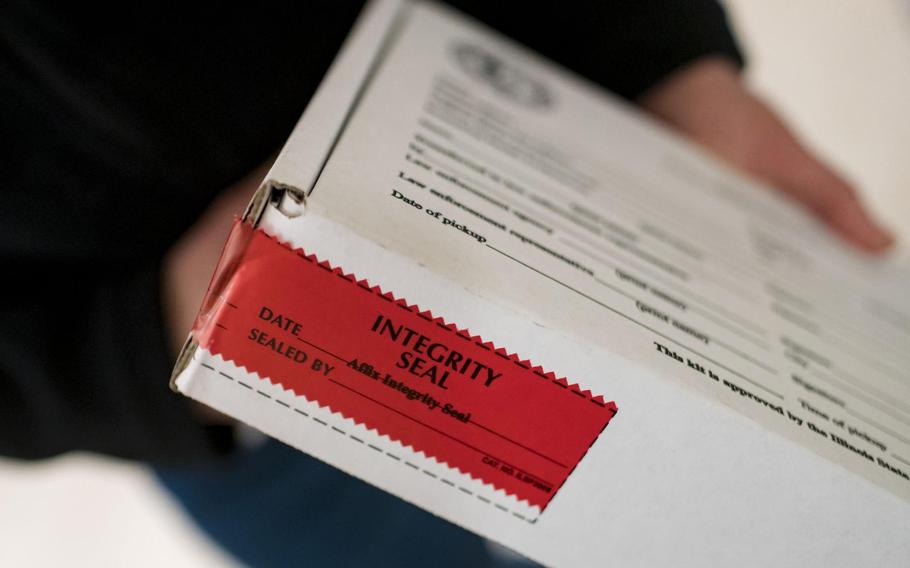

A rape kit on Dec. 4, 2019, in the emergency department at Mount Sinai Hospital in Chicago. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune/TNS)

(Tribune News Service) — By the time she was 23, Madison Campbell had racked up more than a dozen cease-and-desist letters and was seated at a deposition table, staring down lawyers who argued she was endangering the same vulnerable people she claimed to be helping.

In the five years since, the Bridgeville, Penn., native has won accolades for helping sexual assault survivors, first in Forbes magazine, and most recently when she was crowned Miss Pittsburgh in the 2023 pageant — a month before moving her DIY rape assessment startup from Brooklyn to her hometown.

One thing hasn’t changed since she first started promoting Me Too Kits in 2019: Her product hasn’t actually been used in court.

Her adviser, chief operating officer and testing lab each told the Post-Gazette that the carefully packed sets of swabs she now markets as “early evidence kits” cannot be used as evidence at trial. What the tests do tell you, her testing lab in Deerfield Beach, Florida, said, is whether “foreign” DNA is present on your swab.

“You would need more information” to prosecute a case, said Allison Nunes of DNA Labs International.

Campbell, who has said she was a victim of sexual assault in college, makes the case that her startup company, now called Leda Health, is selling a product to help individuals who have been assaulted but don’t want to rely solely on the official process of going to a hospital or to the police to be tested for proof against the perpetrator.

Kits sold by Leda Health are packaged by Morel Ink in Portland, Oregon. They include DNA swabs resembling Q-tips from Puritan Medical Products in Guilford, Maine.

Users are instructed to collect DNA from their mouth and vagina, with the samples then sent — using prepaid shipping labels — to DNA Labs via FedEx. Each kit costs the company $12 to make. They have been sold, so far, to sororities and nonprofits.

The controversy over such kits isn’t limited to those Campbell’s company sells. With reports of huge piles of official rape kits going untested for years in labs around the country — whether because of a lack of resources or differences in priorities — the potential market is there.

But the field of do-it-yourself testing is relatively new, especially as relates to court cases, and lawmakers and industry experts are wrestling with how to regulate them.

While Campbell views her product as an effective way to more easily back up rape allegations, and to promote sexual assault education and support for survivors, attorneys general across the country — and sexual assault prevention specialists — have called the product dangerous. They say the kits could divert people from necessary health care, eliminate paths to justice and offer false hope.

They concede there are flaws in the more official channels used to help sexual assault victims. Backlogs and poor tracking can delay results, certified nurses are in short supply, and the exams themselves can be traumatic.

A number of advocates and experts say they are working toward solutions, but battling with people like Campbell — a tenacious and stubborn entrepreneur — has been exhausting and counterproductive.

Rep. Gina Mosbrucker, a Republican from Washington state who led her state’s effort to ban the at-home kits, recalled an intense fight with Campbell that slowed Leda Health’s push there.

“She was literally flying in with teams nonstop and paying our most challenging lobbyist to wait outside the hearing rooms and to pressure my colleagues,” Mosbrucker said. “She’ll keep going from state to state until she can figure out a way to keep making millions of dollars.”

Campbell said that’s a misunderstanding of her goals, and any profit she makes will only come from a product that people desperately need.

“Eighty percent of sexual assault survivors don’t feel comfortable going to the hospital,” she said. “I was one of those. I was sexually assaulted when I was a junior in college. I didn’t go to the hospital, I didn’t get a rape kit done.”

Guidelines in Maryland

Campbell’s startup has raised almost $10 million in venture capital, much of it during the initial controversy. One of her earliest backers, the New York City venture capitalist Bradley Tusk, said he was impressed by the entrepreneur and thought the kits would fill a need.

“Until you guys can solve the problem yourselves, I’m not gonna apologize. And I wouldn’t ask Madison to stop doing what she’s doing,” he said. “If the nonprofit sector could have solved this problem, they would have done so by now.”

From 2019 to 2022, attorneys general from Washington to Michigan to New York ordered the company to stop selling the kits, arguing “deceptive” marketing tactics would mislead victims.

More recently, Campbell has turned to more niche funding streams, including development contracts from the U.S. Air Force. She also sent 1,000 kits to Ukraine with the goal of prosecuting war crimes.

Her new chief operating officer, Sean Bogle — who joined the startup after overseeing on-campus sexual assault cases as dean of students at Yale University and Stanford — has pushed for a different kind of kit that is less focused on prosecution, which he said is “premature” given the lack of legal precedent.

Campbell said the only change she’s currently making to the kits is to add Spanish instructions to the packaging.

Leda Health is gearing up for a launch in Maryland, despite public pushback from a panel of state experts. Campbell initially described Maryland as her next big win. The company was promoting the kits at colleges around the state, saying that a push for guidelines for such products by state Sen. Shelly Hettleman would allow a mass rollout in October.

In an interview with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Hettleman said those guidelines were meant to be a cautionary measure, not a green light.

“We have made it very clear that we were going to examine what the possibilities were,” she said. “It’s really disappointing that they continue to mislead people.”

Maryland created a policy and funding committee in 2017 solely devoted to sexual assault evidence kits. Under a new law passed last year, the group had to issue a report to the governor and the General Assembly on the potential benefits and pitfalls of at-home kits by December, working in tandem with the state attorney general. The law was focused mostly improving sexual assault evidence collection, preservation and storage.

“There are so many issues that are raised by these kits, we want to make sure that we’re being really thoughtful and comprehensive and putting forth recommendations,” Hettleman said.

That work came as Maryland’s attorney general sent a warning letter to victims’ rights groups, hospitals, universities and local health departments in August, warning that Leda Health was making “false and misleading statements, both verbally and in writing, in promotion of their self-administered collection kits.”

One nonprofit director, Randi Woods, told the Post-Gazette she was ready to promote the kits throughout Maryland. Woods, who leads Sisters Together and Reaching, likened the product to HIV detection kits and said they could be especially helpful to minority communities.

Campbell has described the kits as the next pregnancy test. “Fifty years ago, we used to criticize women for doing at-home pregnancy tests because we thought they were medically unreliable and women couldn’t do it,” she said.

She has also called sexual assault a multi-billion dollar industry.

And that’s part of the problem that Maryland officials and other critics have: They see Campbell as approaching justice for rape as a business, rather than a service.

For example, Leda Health is selling kits to college sororities, even though many colleges offer free resources to victims of assault, said Gabriella Romeo, public policy director at the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape.

Campbell also found a customer in the U.S. Air Force, which has given her company two development contracts — one for $73,879 to study the kits’ usefulness for active duty personnel, another $109,945 to promote sexual assault education and support for survivors.

‘We just need ... buy-in’

Pamela Marshall, director of the forensic graduate program at Duquesne University, has advised Leda Health since 2018, when its kits were still named after the #MeToo movement — the awareness campaign that grew from the exposure of sexual abuse by American film producer Harvey Weinstein in 2017. She said the startup’s current kits aren’t yet ready for court but have come a long way.

“They’re not up to the standard yet,” she said. “But I will tell you that the kit that I have right now has come an astronomical length. Now we just need more of the stakeholders to have some buy-in.”

Campbell likes to point to California as an early proof of concept.

The state tried at-home kits in Monterey County, during COVID and with direct monitoring by a forensic nurse, a detective and a victim advocate. An investigator with that county department said those kits — which were made by another startup, Preserve Group — are no longer in use.

Dr. Reshma Ramachandran, an assistant professor at Yale University School of Medicine, said she sees the intent behind the kits, but finds it “incredibly irresponsible” to promote them as a path to justice.

“I very much hope there is an effort from the FDA to regulate these sorts of tests,” she said. “As doctors, we never want to prescribe or administer a test that’s going to give patients a result that they don’t know what to do with.”

Undeterred, Campbell has looked for new clients overseas.

She sent 250 kits to Kenya. After Hamas invaded Israel, she tried to send kits there.

“But unfortunately, our friends that we were working with in Israel were telling us that rape kits weren’t necessary because of all the women that were getting raped were also getting killed,” Campbell said from the head of a thrifted conference table at her new office in Lawrenceville.

Even if the kits fail, Bradley, her investor, said he’ll support her next venture.

Campbell isn’t ready to give up. She said polling conducted through her new Survivor PAC shows that people want an at-home solution.

Meanwhile, in November, the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape warned prosecutors statewide that at-home kits “leave victims without services and pathways to justice.” It was the same warning the group issued in April 2020. Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen A. Zappala Jr. directed two deputies to look into the warning, a spokesperson said.

Romeo, PCAR’s policy director, said she’d like to work more closely with Campbell to explore solutions for survivors.

The kits are not part of that vision. She described them as a defense attorney’s “best dream.”

“Sexual assault is extremely difficult to prosecute to begin with, let alone when you’re not following the proper channels,” she said.

©2024 the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Visit the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette at www.post-gazette.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.