A staff member stands before a Long March-2F carrier rocket, carrying the Shenzhou-17 spacecraft, on the launch pad encased in a shield at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre in the Gobi desert in northwest China on Oct. 25, 2023. (Pedro Pardo, AFP via Getty Images/TNS)

(Tribune News Service) — Shortly after New Year’s Day in 2019, China landed an unmanned spacecraft on the far side of the moon, where no mission had gone before. U.S. intelligence officials say they did so quietly, taking their time to verify the rover had landed in one piece and protecting themselves from embarrassment. Hours passed before Beijing announced its historic achievement to the world.

The landing was a wake-up call in Washington. China’s space program was advancing with unexpected speed. Beijing would soon assemble in record time a space station orbiting Earth, catching U.S. officials off guard once again.

U.S. intelligence officials acknowledge that China’s sudden advances had surprised them. They are no longer surprised. The intelligence community now assesses with confidence that China is poised to succeed in landing humans on the moon and constructing a permanent base camp at the lunar south pole by the end of this decade, four intelligence officials told McClatchy, just as NASA has fallen behind its own deadlines to achieve similar milestones.

It is the first time intelligence officials have publicly detailed their concerns that China may win the race to return people to the moon and establish a lunar outpost — an achievement that could set back U.S. plans for human space travel for decades to come.

“It wasn’t too long ago that China said they were intending to land by 2035. So that date keeps getting closer and closer,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson told McClatchy in an interview. “I take it very seriously that China, in fact, is in a headlong race to get to the moon.”

Neither country plans to stop at the moon. Both see it as a training ground for missions to Mars in the 2030s, vying to make history by sending humans deep into space and landing them for the first time on another planet.

“Before, it was more of an afterthought — China was nowhere to be seen,” one U.S. intelligence official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive intelligence matters. “Today, China gets the lion’s share of intelligence attention.”

A second U.S. intelligence official said that “space is very evident to China as a place they need to counter U.S. power.”

“They don’t want to be the space power of the 2020s,” the official added. “They want to be the space power of the 21st century, the way we were in the 20th.”

More than half a century after the United States put men on the moon, a space race is on for the new millennium. The first great competition of world powers since the end of the Cold War is spurring a new era of exploration that could send humans on missions far beyond those of the Apollo program 50 years ago.

But if the original space race with the Soviet Union was a sprint, this new competition with China is going to be a marathon.

“The United States will continue to lead the world,” Vice President Kamala Harris, who also serves as director of the National Space Council, told McClatchy in a statement. “Our unrivaled network of allies and partners will power our deep space exploration, inspire the next generation of explorers, and will ensure that advancements in space benefit all of humanity.”

At NASA, all of these goals are linked, forming a “Moon to Mars Architecture” that is breaking modern precedent in Washington for space initiatives with sustained support and funding from consecutive Republican and Democratic administrations.

“Is China a catalyst? It should be. Chinese ambitions for both the moon and Mars should be taken very seriously,” said Dean Cheng, senior adviser to the China program at the U.S. Institute of Peace. “Because from their perspective, it’s not just about planting a flag. There’s a whole freight train worth of baggage and meaning associated with both of these missions.”

“This is to establish presence,” Cheng said, “but then to establish the rules.”

Competition is already inching toward conflict closer to home. Since landing a rover on the far side of the moon, China has more than doubled its number of satellites orbiting Earth, and has launched a space plane that remained in low-Earth orbit for several months before ascending and releasing a projectile, defense officials said. Beijing is already fielding weapons in space, including electronic and cyberspace equipment, but also devices that can stalk and latch on to satellites to disrupt their orbit.

Nelson expressed concern that China may reach its lunar milestones first — a development that could allow Beijing to monopolize resources critical to a sustained presence on the surface, such as frozen water hiding in crevices of permanent darkness, and solar energy from mountain peaks bathed in eternal sunlight.

“If China were to land and begin an outpost there, I think it would be a Sputnik moment for the American people,” said G. Scott Hubbard, NASA’s first Mars czar and former director of the Ames Research Center at NASA who now chairs SpaceX’s crew safety advisory panel. “They could claim it as their own.”

The Chinese Embassy in Washington told McClatchy in a statement that “outer space is not a wrestling ground, but an important field for win-win cooperation. The exploration and peaceful uses of outer space is humanity’s common endeavor and should benefit all.”

Senior officials in the Biden administration told McClatchy that China’s program could be the motivation the United States needs to reestablish the wonder and drive of spaceflight that once captured the American imagination. “There are positive aspects to competition,” one official said, adding, “one person’s pressure is another person’s inspiration.”

Dash to the lunar south pole

Beijing surprised Washington once again in May, when its military-run Manned Space Agency held a press conference ostensibly to deliver a routine announcement.

Agency officials were introducing three new Chinese astronauts who would depart for China’s Tiangong Space Station the following day — part of a steady cadence of new crew members being sent into orbit every six months, an impressive achievement in and of itself. Then officials added that Beijing intends to land humans on the moon by 2030, moving their timeline up by years.

China’s Academy of Military Sciences has previously said that space “has already become a new domain of modern military struggle.” Neither the China National Space Administration nor the China Manned Space Agency responded to multiple email requests for comment.

China’s public plan is to use robots to scout the south pole for lunar water in 2026 and begin establishing its base there, to be called the International Lunar Research Station, in 2028. Beijing aims to complete a new Long March 10 rocket system for its crewed missions by 2027.

U.S. intelligence officials say it would be “high risk” for the Chinese to attempt their first human landing at the south pole, but also believe Beijing will try to distinguish their first landing from Apollo.

“If there is a prestige goal,” one intelligence official said, “it is the south pole of the moon.”

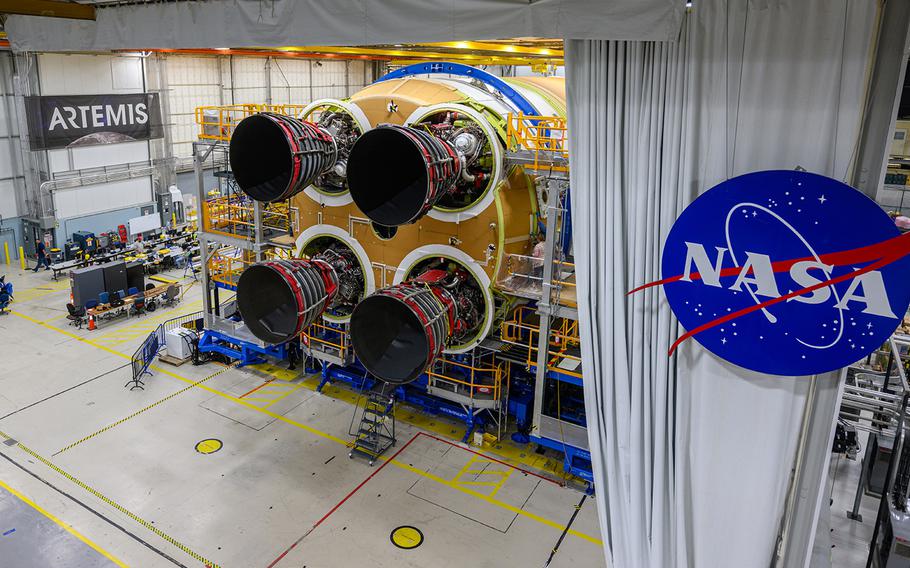

Spurred to action by China’s sudden advances, the Trump administration launched the Artemis program, which began with an uncrewed orbital mission in 2022. NASA plans for a crew to orbit the moon next year with Artemis II. Then, in December 2025 — already a year later than initially anticipated — Artemis III plans to return a crew to the moon for the first time in over 53 years, including the first woman and first person of color.

But a senior NASA official said in a public meeting over the summer that “difficulties” facing SpaceX, the private company building the spacecraft NASA plans to use for the Artemis III mission, could cause further delays.

Technicians at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans install the third and fourth RS-25 engines onto the core stage for the agency’s SLS (Space Launch System) rocket. Technicians added the first engine to the SLS core stage Sept. 11. The second engine was installed onto the stage Sept. 15 with the third and fourth engines following Sept. 19 and Sept. 20. (Eric Bordelon/NASA/TNS)

SpaceX’s Starship spacecraft has never successfully flown in orbit, and must do so several times before flying Artemis III for NASA. Recent setbacks in the program have been mocked and celebrated on Chinese state media. SpaceX declined multiple requests for comment.

Nelson acknowledged in the interview that Artemis III may have to be pushed back. “There may be some slippage,” he said.

If Starship fails to meet the moment, Washington may well lose the immediate race to the moon and have to start over on its planning architecture for Mars. SpaceX is expected to attempt a second orbital launch this weekend. A senior administration official told McClatchy that the White House would be monitoring the test and its impacts on the Artemis timeframe.

NASA has also been noncommittal on its plans for a lunar base. As recently as 2022, the agency said it planned to establish an Artemis Base Camp at the south pole by the end of the decade. But it has since gone quiet on the plan. NASA’s most recent budget to Congress referenced a “foundation surface habitat” at the south pole as a “key element” for future missions, but offered no timeline.

NASA told McClatchy it is still working to “develop the infrastructure needed for a long-term human presence” and provided no new schedule for the outpost, other than to say that, after returning humans to the moon, missions beyond Artemis IV in 2028 will establish an “annual launch cadence.”

But if China continues to meet its own timeline, as the U.S. intelligence community expects, then by 2028, its Chang’e 8 mission will have already begun laying the foundation of their base at the south pole — and the stage for a potential battle over sovereignty, location and lunar resources.

“To do all of this, you need energy. And there are some tiny slivers of land right alongside suspected water in the permanent shadows — I’m talking about a few thousand acres — that are in near-continuous sunlight,” Hubbard said. “Both the United States and China are aiming for those peaks of eternal light as a base.”

There is no precedent for such a conflict and no laws to govern it outside a 1967 treaty widely seen as thin and unenforceable, said Thomas Roberts, adjunct fellow with the CSIS Aerospace Security Project.

“Both actors want to go to the same small region of the lunar surface at the same time,” Roberts said. “If you were to land another lunar lander somewhere near an existing site, the physical nature of the lunar regolith would inspire a debris cloud that could really tamper with sensitive instrumentation.”

“That’s totally fine if your goal is to visit the far side of the moon, which is the size of an ocean,” he added. “It’s less fine if you’re looking for particular properties of lunar rotation that happen in a tiny fraction of territory.”

U.S. officials are increasingly concerned that, should it achieve dominance at the south pole, China could indeed attempt to deny physical access to the United States and its partners, limiting their ability to sustain a permanent presence on the surface or reach rare minerals and isotopes increasingly scarce at home.

“We believe they will try to exploit lunar activity to the max,” one of the U.S. intelligence officials said. “China may have the ability to create an advantageous position to influence the movement of other powers, including the United States, to and around the moon.”

Washington has tried to create a new set of rules to govern this otherwise untamed frontier, drafting the Artemis Accords to “set out a practical set of principles to guide space exploration,” according to the State Department. The list of signatories has grown to 32 nations. China is not among them. Instead, Beijing has recruited a small list of countries to join its lunar base program including Russia, Venezuela, Pakistan, South Africa and Belarus.

Three senior Biden administration officials told McClatchy that the White House believes there is still time to “shape the environment” for what kind of behavior the world will accept from the future of space travel.

“The next few years — and especially the next year or two — is going to be about the United States continuing to exert leadership to set the norms and standards that we want, and aligning with our partners,” one senior official said.

Another senior administration official described the prospect of “keep-out zones” on the moon as a “pressing topic” frequently discussed at the White House. But a law called the Wolf Amendment, passed during the Obama administration amid revelations that Beijing had used information from satellite companies to advance its ballistic missile technology, bans officials from NASA and the White House from directly engaging with China on space matters.

“We do envision that those types of discussions will eventually happen,” the second senior administration official said. “But I think right now, we’re really focused on being able to develop our capabilities and our technologies and our programs. And I have to believe the Chinese are similarly focused.”

In Congress, lawmakers on the intelligence committees have been briefed on China’s plans and are pressing NASA to meet its deadlines, Sen. Jerry Moran of Kansas, the top Republican on the Appropriations Subcommittee with jurisdiction over NASA, said in an interview.

“As Americans — perhaps in part out of pride, but out of national security and economic benefit — we do not want to see China plant a flag on the moon or be in deep outer space, including Mars,” Moran said.

U.S. officials huddled with their allies this summer in London to discuss the strategy of their upcoming lunar and Martian missions, focusing intensely on Beijing’s intentions, said Nicolas Maubert, space counselor at the French Embassy in Washington. France has relationships in space with both China and the United States.

“We see what China is doing — they’re moving really, really fast,” Maubert said.

The ‘horizon goal’ of Mars

The point of returning to the moon is not, as Maubert put it, “for the pleasure of staying on the moon.” It is to learn how to keep humans alive on a celestial body for long periods of time before venturing far beyond — to Mars.

But traveling to Mars makes a trip to the moon look easy, said Jim Bridenstine, NASA administrator under former President Donald Trump.

“Humanity is going to eventually walk on the surface of Mars, and I think that is going to be an exceptional moment,” Bridenstine added. “Who will be there first? I don’t know.”

With conventional technology, launch opportunities to Mars come along just once every 26 months. It is roughly an eight-month journey each way. Missing a launch window could mean a delay of several years, and if something goes wrong midflight, the crew will be on its own in deep space.

The sheer length of the journey means a crew will be exposed to dangerous levels of radiation and need more food, equipment, and physical and mental stamina than any previous mission ever tested.

Then they will have to land through an atmosphere that is thick enough to kill them but too thin to be used as a break to slow their descent to the surface. Should they succeed, they will be on the other side of the sun with no one there to help them.

“Artemis is a step towards Mars in the way that taking a step out of the front door of your house in New York is a step towards Paris,” said Casey Dreier, chief of space policy for The Planetary Society, a space policy advocacy group founded by Carl Sagan.

NASA aims to reach Mars by 2040 and is working on entirely new technologies for the mission, Nelson told McClatchy, including the production of a nuclear thermal propulsion engine that NASA hopes will cut the travel time in half.

Tabitha Dodson is leading the effort at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, to resurrect a thermal nuclear engine project that first began in the Apollo era but sat on a shelf after the United States abandoned manned spaceflight in the 1970s.

“I feel a very powerful sense of urgency,” Dodson told McClatchy. “There’s just this perfect storm of support, all up and down the various government agencies nationwide — in Congress and at the presidential level — to the point where I feel like we have to get this done, right now, because we might miss our chance.”

Dodson said she has “high confidence” DARPA and its main private industry partner, Lockheed Martin, will successfully demonstrate their rocket, known as DRACO, in 2027.

From there, dozens of scientists led by a team out of the Idaho National Laboratory are working to build on DRACO’s anticipated success, increasing the efficiency of the components necessary for a nuclear thermal rocket to work on longer missions.

“There’s additional technology that needs to be developed to have the higher capability that you need for the Mars mission,” Sebastian Corbisiero, senior technical advisor for advanced concepts at the Idaho National Laboratory, said in an interview.

Dodson and Corbisiero both acknowledged working toward an internal deadline of reaching Mars by 2040 and expressed confidence it could be reached.

Chinese officials, too, appear to be working on a nuclear propulsion project of their own.

Last November on Hainan Island, where China has built a launch site for its heaviest rockets, Wu Weiren, an architect of China’s lunar program, made a presentation that previewed China’s plans for future missions that included spaceship designs to accommodate nuclear electric engines, according to slides of the proposal obtained by McClatchy.

“Mars is the horizon goal,” said Scott Pace, executive secretary of the National Space Council under Trump. “Landing on Mars — if they’re able to do it — would play into China’s narrative as the great power of the 21st Century. But having that goal and doing it are two different things.”

Chinese officials have remained quiet on their plans for a manned mission to Mars. In 2021, at a conference on space exploration in Russia, a senior executive at China’s main space launch vehicle manufacturer said that Beijing had a roadmap to send humans and establish a base there in the mid-2030s.

The fate of China’s robotic rover on Mars, sent with great fanfare the same year but that died just months into its mission, may have demonstrated for Beijing the challenges ahead. “They are discovering that Mars is hard,” one U.S. intelligence official said.

U.S. officials dismissed the executive’s remarks, questioning the viability of such an aggressive timeline and whether he was speaking for the government.

But state media reported on it. And it would not be the first time that Beijing’s space program surprised the world.

“The Chinese say this all the time: Crawl, walk, run,” said Cheng, of the U.S. Institute of Peace. “They invoke this for every major scientific program.”

“They take their time at first,” he added, “but culminate in a sprint.”

©2023 McClatchy Washington Bureau.

Visit mcclatchydc.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.