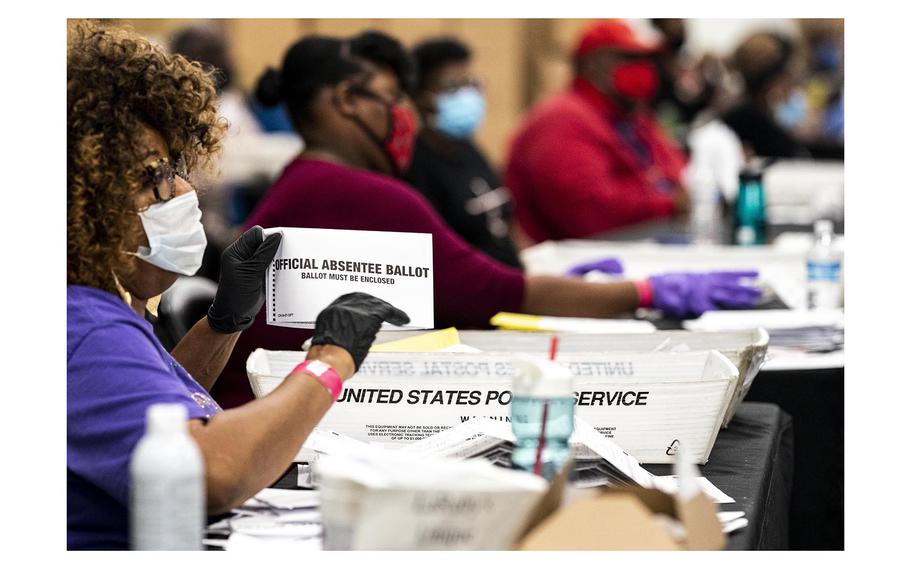

Ballots are processed at the Elections Preparation Center at State Farm Arena in Atlanta on Nov. 3, 2020. (Melina Mara/The Washington Post)

When lawyer Jenna Ellis pleaded guilty to election interference in Atlanta late last month, she tearfully told the judge, “If I knew then what I know now, I would have declined to represent Donald Trump in these post-election challenges.”

Kenneth Chesebro, another attorney who pleaded guilty in the Fulton County, Ga., case, for his role advising President Trump during his effort to reverse his 2020 defeat, also said he no longer believes the claims still voiced by Trump and many of his allies that the election was stolen. “If you ask Mr. Chesebro today who won the 2020 presidential election,” said his lawyer, Scott Grubman, “he would say Joe Biden.”

But more recently, a novel defense has been emerging from two of Trump’s remaining 14 co-defendants in Georgia, where prosecutors allege there was a vast conspiracy to steal the 2020 election through a pressure campaign that included cajoling state officials, harassing local election workers and urging illegitimate Trump electors to cast ballots in seven states that Joe Biden won.

The argument? The 2020 election really was stolen.

Lawyers for one of those defendants, Harrison Floyd, appeared in court Friday morning to argue that their client is entitled to thousands of pages of election records from Fulton County and the Georgia secretary of state.

“They opened the door - we didn’t,” Chris Kachouroff, one of Floyd’s lawyers, argued during the hearing - a reference to the Fulton prosecution team’s language in the indictment stating that Trump lost. “We have the right to rebut that.”

To do so, Floyd’s lawyers argued, they must be allowed access to some of the same material for which election conspiracy theorists have been clamoring for years: cast-vote records from voting machines, ballot reports, every envelope received with absentee ballots, every absentee ballot application and much more.

The argument serves as a major test of the breadth of the Fulton indictment. Because prosecutors have alleged that Floyd and the other defendants “knowingly” lied, his lawyers say they have the right to try to prove it wasn’t a lie at all.

The issue could also test Fulton County Superior Court Judge Scott McAfee, who is presiding over the case and has shown a tendency for discipline and tight deadlines. Floyd’s defense strategy gives McAfee a potential opportunity to rule from a courtroom that the 2020 election was not stolen - or, in the alternative, to give election deniers space to make their preferred defense, but in the process potentially giving them a new platform to disseminate false claims and further complicate an already sprawling case.

In their brief, Floyd’s lawyers indicated plans to examine many of the same claims that circulated in 2020 among Trump loyalists but were dismissed in multiple court cases - that tens of thousands of votes weren’t verified, that some ballots were counted two or three times, and that a “legion” of other irregularities “clearly affected the result.”

Dozens of judges across the political spectrum ruled against Trump’s efforts to overturn Biden’s victory in the 2020 presidential election, including in Georgia.

Floyd, a little-known player who helped run Trump’s 2020 campaign outreach to Black voters, faces three charges in the Fulton case: racketeering, conspiracy to solicit false statements and influencing witnesses. The charges stem from his alleged efforts alongside a professional publicist and a preacher to pressure a local election worker, Ruby Freeman, into confessing to election crimes that she did not commit.

Freeman was the target of repeated false statements by Trump and his supporters in the days and weeks after the 2020 election. The then-president mentioned her 18 times in a phone call with Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R) on Jan. 2, 2021, at one point calling her a “professional vote scammer and hustler.”

Whether McAfee will allow such an unwieldy volume of information into the case - and the chaos it could create - is uncertain. A key question for McAfee to consider is whether Floyd - and potentially other defendants, whose lawyers watched Friday’s hearing with great interest - is entitled, as part of his defense, to cast doubt on an election result that has been decided.

On Friday, McAfee appeared torn between the rights of defendants facing potential prison sentences to compel the production of evidence that could prove innocence and the burden that such production could generate - not just on government agencies but on the private citizens whose personal information could be revealed.

McAfee at times appeared skeptical of the arguments made by Floyd’s attorney, at one point telling him “the amount of personal information” that might be contained in the material was a “big red flag” for him.

Jackson Sharman, an attorney for Raffensperger’s office, said it could take five to six months to produce the material. Chad Alexis, a lawyer for the Fulton County clerk, said it could take even longer given that the request for information from Fulton was even broader.

Kachouroff, the Floyd lawyer, said he could scale back the subpoenas. He also made clear that Floyd will pay for document production.

McAfee asked Floyd’s attorneys to file amended subpoenas by Monday, and he asked the state agencies to respond with a detailed timeline of how long it would take, and how much it would cost, to produce the information. The judge will then write a detailed analysis as part of his decision, he said - meaning it could be weeks before the skirmish is settled.

“I would like to go down this road . . . and dig a little deeper” on the question of burden, McAfee said, adding he hoped to use that information to determine the relevance the material Floyd is seeking in a “comprehensive ruling” that would limit the back-and-forth on the issue moving forward.

“It almost seems from the case law that something could conceivably be relevant but maybe be so burdensome that it can still be quashed,” the judge said.

According to his lawyers, Floyd should have the right to dispute a basic premise of the Georgia indictment, that Biden won in 2020, to undermine prosecutors’ key allegation - that he knew his statements about 2020 were wrong.

Floyd “intends to negate criminal intent, and to rebut the indictment’s ‘knowing and willful’ allegations and false statements,” his attorneys wrote. He can’t do that unless Raffensperger and the Fulton County Board of Elections are compelled to produce the documents he has demanded. Those agencies’ efforts to block Floyd’s subpoenas were the subject of Friday’s hearing.

Kachouroff also said during the hearing that “we are not trying to re-litigate the election” - an apparent contradiction of his prior statements that drew a skeptical reaction from McAfee. He said examining the election records is necessary to either prove that Floyd is innocent, because the election was indeed stolen - or to prove the election was not stolen and Floyd is innocent under a “mistake of fact” defense.

Frank Hogue, one of Ellis’s lawyers, said in an interview that he thinks Floyd’s argument is proper, because he has a right to examine evidence to determine which is the best defense.

Hogue said Ellis’s defense, had she gone to trial, would have mirrored one of the arguments Kachouroff said he was considering for Floyd - a “mistake of fact” argument, that she believed at the time that irregularities had tainted the outcome and did not intentionally deceive anyone.

But Hogue also said it’s potentially perilous for Kachouroff to try to prove to a jury that the election was tainted.

“I think as a defense lawyer, you never want to take on a burden to prove a thing you don’t have to prove,” Hogue said. “It’s the state’s burden to prove stuff, not ours.”

Floyd is not the only defendant seeking to re-litigate allegations of irregularities in the 2020 election. In Washington, Trump’s lawyers in his federal election obstruction case have argued for the charges against the former president to be dismissed in part because his claims were protected by the First Amendment right to free speech.

“The fact that the indictment alleges that the speech was supposedly, according to the prosecution, ‘false’ makes no difference,” Trump’s lawyers wrote in a recent filing. “Under the First Amendment, each individual American participating in a free marketplace of ideas - not the federal Government - decides for him or herself what is true and false on great disputed social and political questions.”

Trump’s legal team has also signaled they intend to introduce classified evidence “relating to foreign influence activities that impacted the 2016 and 2020 elections, as well as efforts by his administration to combat those activities,” adding they plan to show that he “acted at all times in good faith and on the belief that he was doing what he had been elected to do.”

And lawyers for another co-defendant in the Georgia case, Robert Cheeley, also signaled in a recent filing that litigating claims about Georgia’s 2020 presidential election is likely to be key to his defense.

Cheeley, a pro-Trump Atlanta-area attorney, is facing 10 charges in Fulton. Prosecutors allege he played a wide-ranging role in seeking to subvert Georgia’s election results to keep Trump in power, including making false statements at a state legislative hearing, where he claimed election workers were double- and triple-counting ballots.

In a recent filing seeking to dismiss charges, Cheeley, who is the lead attorney in an ongoing pro-Trump lawsuit seeking to review thousands of Fulton County ballots cast in 2020, produced a transcript of his remarks at that December 2020 hearing and sought to introduce into evidence a video of the proceeding, which shows him narrating a video that he told lawmakers proves there was fraud at a ballot counting site at State Farm Arena in Atlanta.

Cheeley’s attorneys claim in the filing their client “simply brought public attention” to a “potentially flawed vote-counting process.”

“The State indicted Cheeley for engaging in protected political and civil activity as an advocate for his clients because he expressed concerns regarding the election results before a Georgia Senate subcommittee and because he advocated for his clients’ positions,” Cheeley’s attorneys wrote. “Raising these concerns is not a crime.”

In a footnote, Cheeley, through his attorneys, threatened to call Fulton County District Attorney Fani T. Willis (D), whose office is leading the criminal case against Trump and his allies, to question her about public statements she had made about the 2020 election and her subsequent investigation of election interference - claiming her outspokenness about election issues were no different from his statements.

Absent from the hearing about Floyd were members of the prosecution team, who did not weigh in with any court filings staking out an argument on the subpoenas. Floyd did not attend the hearing.

Bailey reported from Atlanta. Devlin Barrett in Washington contributed to this report.